It's been more than a year since Minh Phan closed his Los Angeles restaurants, but the refrigerator at his former Porridge + Puffs diner in historic Filipinotown is full. The shelves are lined with tall containers filled with aqua blue passion fruit alginate, cardamom alginate and jet black coffee and jars of products in various stages of fermentation.

Minh Phan experiments with the use of different seaweeds as coagulants for a passion fruit jelly.

(Shelby Moore / for The Times)

Porridge & Puffs was Phan's rice temple, a pop-up-turned-restaurant where he took humble bowls of porridge and transformed them into some of the most captivating dishes in the city. He followed up with Phenakite, his Hollywood fine-dining restaurant, opened during the COVID pandemic in 2020. In his brief tenure, Phenakite racked up the highest accolades, including this newspaper's Restaurant of the Year award in 2021, followed by a star Michelin. At one point, according to Variety, there were 20,000 people on the Phenakite waiting list.

However, Phan couldn't help but encounter the reality that the always precarious restaurant industry has been under enormous strain since the pandemic, as evidenced by the spate of closures we've seen in Los Angeles in recent years. .

Phan is also the first to admit that running a business and managing people are not skills that come naturally to her artist persona.

In the newly released documentary “Food and Country,” directed by Laura Gabbert (“City of Gold”), Phan says that when he tried to equalize the disparity between kitchen staff and servers by paying both equally, he couldn't find many servers. . willing to work for $20 to $25 an hour.

“I got a lot of criticism from people about why I closed [the restaurants]”she says. “There were many reasons, but the job was no longer useful for what I want to do. Food is ephemeral. “

In a recent episode of Kenneth Nguyen’s “The Vietnamese” podcast, he talked about the way we, as a society, view food.

“Why don't we look at food like we look at museums?” she says. “And get grants?”

With these thoughts in mind, Phan decided that instead of focusing her attention on running another food hall, she would become the artist-in-residence for Food Forward, a nonprofit that recovers and then donates surplus produce from the LA Wholesale Produce Market. plus other growers and produce shippers, as well as leftovers from farmers markets and backyard tree harvests. More than 250 hunger relief and community groups receive deliveries from Food Forward, which moves approximately 280,000 pounds of otherwise wasted produce per day through Pit Stop, its 16,000-square-foot refrigerated warehouse in Bell.

“Minh and Food Forward share many values and deep thinking about food and who can eat,” says Rick Nahmias, founder and CEO of Food Forward, now in its 15th year. “[This] “It is an opportunity for us to cross audiences and amplify the meaning of nutritional equity, food equity and building generational health.”

Minh Phan at the Food Forward pit stop in Bell. Phan is the nonprofit's new artist-in-residence.

(Shelby Moore / for The Times)

Nahmias and Phan met years ago and have been talking about working together in some capacity for a while now. The artist-in-residence role draws on Phan's experience as an artist, filmmaker and chef to help raise awareness of Food Forward's food conservation efforts. Phan spent years in the film industry, building installations, working in graphic arts, writing, directing and art directing. He produced commercials and worked on numerous films, including “Dazed and Confused,” “The Big Lebowski” and “Being John Malkovich.” For Glenn Kaino’s 2022 exhibition “A Forest for the Trees,” “about reinventing our relationship with nature,” as the artist described it, Phan created a teahouse where gallery-goers could eat brown butter mochi and talk about their experiences in the gallery.

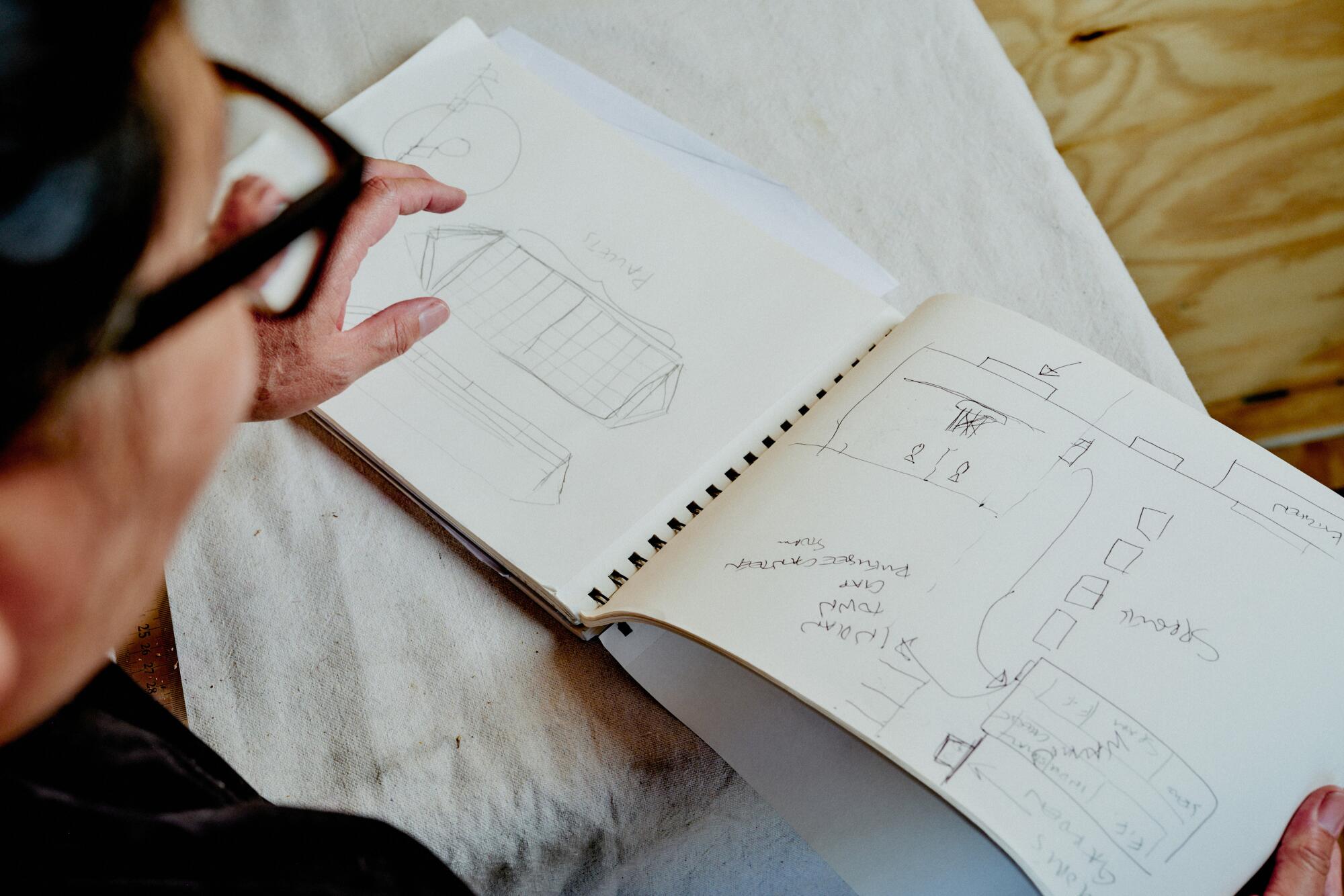

In his new role, Phan has spent the last few months creating an immersive exhibit that will be unveiled on October 19 at a ticketed event benefiting Food Forward. The evening will include a guided tour through an art exhibit that incorporates storytelling and a performance, and a sit-down meal that will evolve into what Phan calls two backyard parties.

Materials for the fair, such as wooden boards, pallets and cardboard boxes, come from Food Forward's Pit Stop warehouse. For food, prioritize seeds, peels, spent pulps and purees that would otherwise end up in compost, as well as algae, invasive wild mustards and radishes. Some of the products will come from a list that the Food Forward team calls “challenging” due to the difficulty some agencies and recipients experience when trying to use them. Bok choy, peas, and Buddha's hand (finger citron) are considered challenging.

Phan's initial mission was to find ways to reuse food waste, exploring what he could do with items like rotten fruits, leftover purees, teas and coffee grounds. He also wanted to get certified to drive one of the forklifts that transport pallets of products. His attention widened when he noticed a series of footprints running across the warehouse floor.

After investigating the site, Phan discovered that the building was formerly the Cheli Air Force Station, a site where bombs were tested during the Cold War.

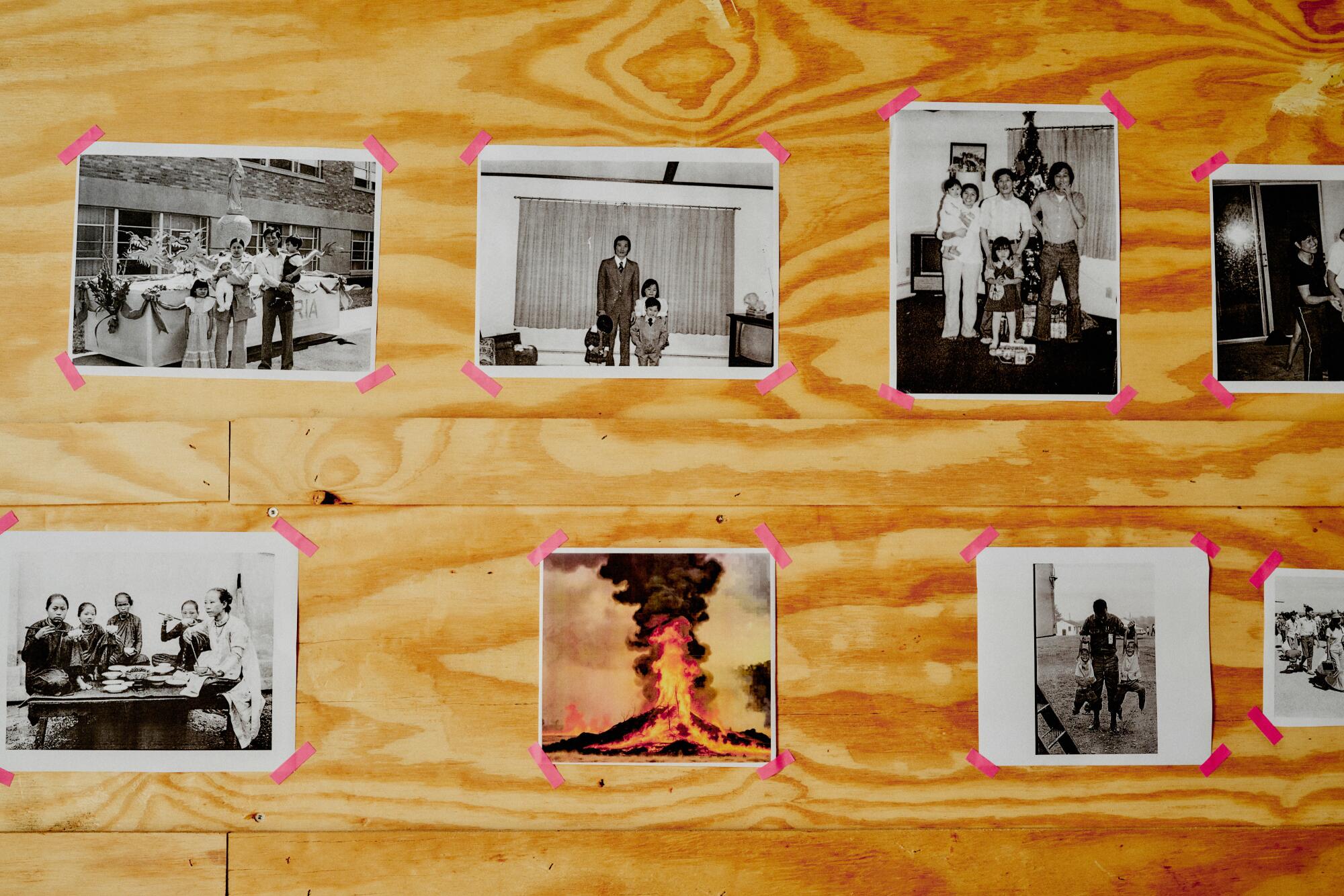

“I come from the bombs,” says Phan, whose parents fled Vietnam during the fall of Saigon in 1975, when she was two years old. “I wouldn't be here if it weren't for the war and the bombs.”

A collection of photographs posted inside Minh Phan's trailer studio at Food Forward Pit Stop help inspire his work.

(Shelby Moore / for The Times)

“It turns out that 2025 will be the 50th anniversary of Black April,” he says. “I came up with 10 different installations that I wanted to represent what Food Forward and the space meant to me.”

Each of the installations is designed to use Phan's personal story to unlock the collision of war, one of the most unnatural things in the world, and the most natural act of feeding people.

“I've always expressed myself by sharing with others the things that matter to me,” Phan says. “In that sense, this [project] It really brings my work together. “I tend to lean a lot towards ethnographic questioning in everything I do and I think that is the basis of a lot of my work.”

He is using a trailer studio at Pit Stop, in addition to the former Porridge & Puffs space, as an artist studio, workshop materials and exhibition ideas. She brings a small replica of a sailboat made from an empty Philadelphia cream cheese container and old business and membership cards.

Minh Phan shows off early food waste experiments inside his rolling studio at the Food Forward Pit Stop in Bell.

(Shelby Moore / for The Times)

One of the exhibits will depict the boat that Phan imagines his parents and other refugees traveled on when they fled Vietnam. On the tracks where the bombs used to be mounted, Phan will build the boat and fill it with the items a refugee would carry with them.

“There are only two things: food for the future and language and ideas,” he says. “Language and ideas are kept here and here, no one can see them, and they are kept as tight as possible.” He points to his head and then his heart.

“And as food, seeds are saved,” he says. “I want to build a boat with food and seeds and I'm going to write poetry that I'm hiding in the boat to represent these people on the boat.”

Another facility, titled Indiantown Gap Refugee Canteen Storage, will turn Pit Stop's 2,000-square-foot cold storage into a sort of mock food pantry filled with items made to look like spam, gelatin and industrial cheese. Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, is where Phan's parents landed in May 1975.

“I want to make it clear that without Food Forward there would be no foods that are understandable to other cultures, and that is the heart of what my work has been for the last few decades: the cross-cultural understanding of ingredients and foods.” Phan says. “By the very nature of Food Forward, it allows immigrants and those who are different to have a language of their own that is not spam, gelatin or processed cheese.”

Phan is also recreating what she calls her mother's cross-cultural garden. For the past 40 years, her mother has grown medicinal herbs and produce at the family home in Huntington Beach. Phan remembers her mother telling her to go to the garden as a child and count how many leaves were on a specific tree, hoping that the detailed task would help her with her ADHD. She never reached 100 leaves, but Phan's time in her mother's garden taught her about nature and the seasons, how things die and grow.

“I want everyone to have a cross-cultural garden,” he says.

The first course of the evening will be served in a garden that Phan will create in the warehouse. He'll also serve a version of the spring rolls his mom made him to take to a show-and-tell day at his high school.

Minh Phan shares a notebook of ideas for his art installations on Food Forward.

(Shelby Moore / for The Times)

“We were so poor, what do we show and what do we tell?” Phan says, remembering his family's confusion. “It was Wausau, Wisconsin, and I was the only person of color. My mom said, this is what our people eat, show them this.”

For now, Phan's exhibit will only be available on October 19, but his goal is to keep it on Food Forward and open it to the public.

“To let others know about Food Forward,” he says, “and the work they do while they think.”[ing] about immigrants, food insecurity, food injustice. … It all comes down to financing and logistics.”

Phan describes his relationship with Food Forward as evergreen and plans to provide a sort of guide and recipe cards for how groups can use some of the lesser-known ingredients they receive from the organization. And he already has other installations that he has started working on, never having less than a dozen loose concepts in mind at a time.

“I really want to collapse and integrate food into the art world so that it is preserved institutionally. The value of food and food workers is greatly reduced because we do not value it as something cultural. … I would like this work to be part of the zeitgeist.”

For more information or to purchase tickets to the Phan's Food Forward show and dinner on October 19, visit foodforward.org.