Antonio Gutiérrez, who worked as a waiter in the Warner Bros. cafeteria in the 1960s, regularly waited tables for Hollywood heavyweights.

Frank Sinatra. Jane Fonda. Francis Ford Coppola. Barbara Streisand. And Jack Warner, the head of the Burbank studio.

Gutiérrez had emigrated from Mexico a decade earlier with the dream of opening his own restaurant. So, when he had the opportunity, he asked Warner for advice about it.

“Don't get into the restaurant business!” the head of the studio told him, one of Gutiérrez's daughters recalled. “You won't make any money!”

Gutiérrez was undeterred: He opened Antonio's on Melrose Avenue in 1970. The Mexican joint soon became a hangout for some of the artists Gutiérrez had once catered to, and its walls were a testament to that patronage, filled almost to the ceiling with framed photographs of the restaurateur alongside artists like Sinatra and Coppola.

But people didn't come to Antonio's house just to see a potential celebrity. From the beginning, in a Los Angeles awash in gooey spectacles of refried beans and orange cheese from the Cal-Mex combo plates manual, Antonio's offered items rarely seen on Southland menus: Chicken In Pipian, chilis in nogada and Red snapper Veracruzana.

Critics noticed it.

“Until the new wave of places like Border Grill and Tamayo, Antonio's was the main—virtually the only—Mexican place that consistently broke away from the narrow world of enchiladas and tamales,” 1988 Times review of a comparatively short-lived restaurant. He told the restaurant's location in Santa Monica.

Gutiérrez, who closed the Melrose mainstay in 2022, died at his home in Los Angeles on September 15 after battling Parkinson's disease, his daughter Irma Rodríguez said. He was 85 years old.

His death and the quiet closing of Antonio's are a reminder of what has been lost amid an avalanche of restaurant closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors. More than 65 prominent Los Angeles properties closed in 2023.

Gutierrez's family chose not to make his death public last fall, preferring to grieve privately, Rodriguez said. Now, however, he believes that “many would like to know” the story of his father.

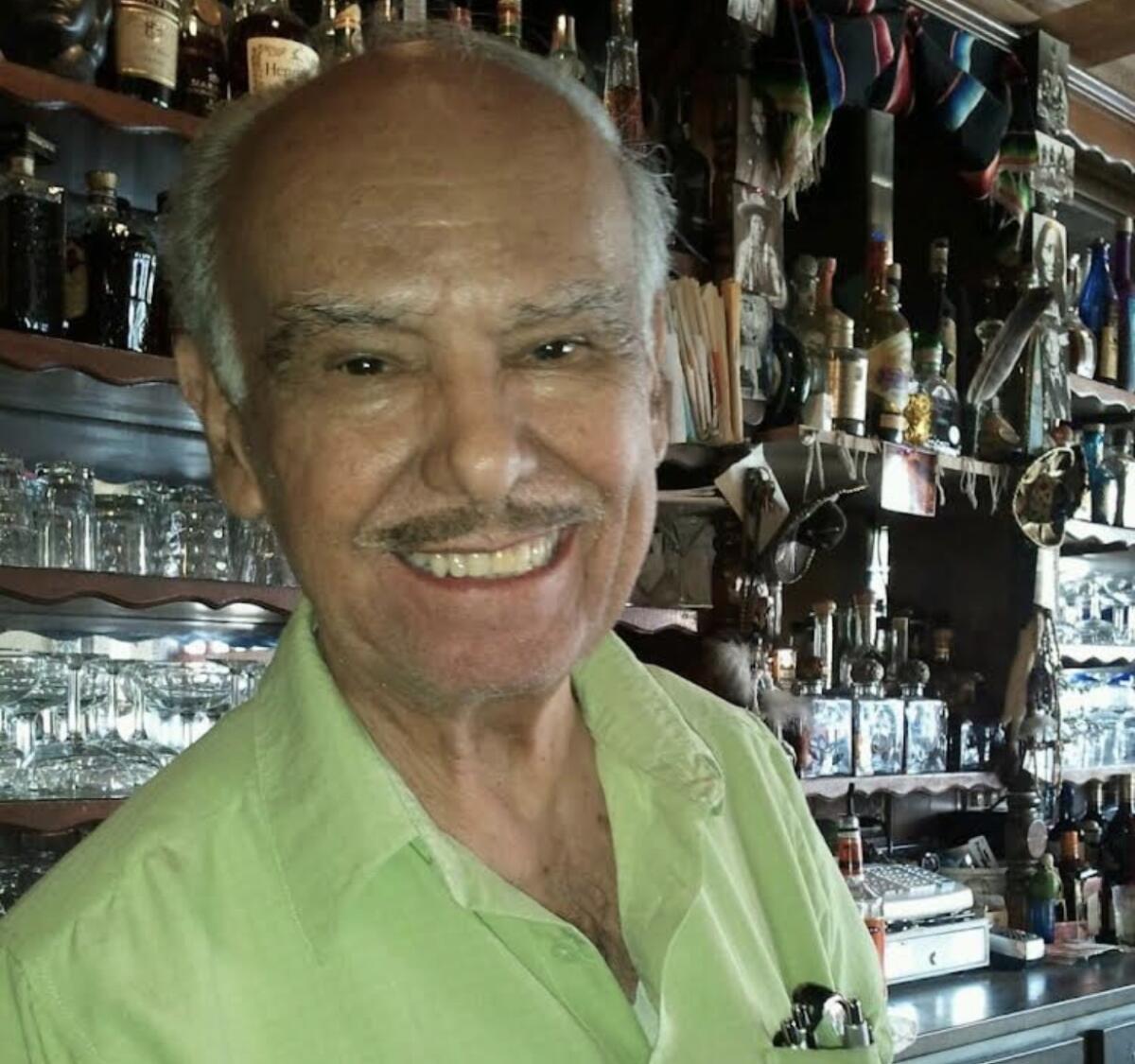

Antonio Gutierrez, the restaurateur behind Antonio's on Melrose Avenue, in the late 1950s.

(Courtesy of Irma Rodríguez)

“He was a very happy man when he took care of people at the restaurant,” she said. “That was the greatest pleasure of his life, because it was his dream.”

Antonio López Gutiérrez was born in Monterrey, Mexico, on Oct. 25, 1937. One of 10 children, as a teenager he worked at a local newspaper, where he operated the printing press and later managed it, Rodríguez said. After about three years, he said, Gutiérrez had saved enough money to leave General Terán, a municipality on the outskirts of Monterrey, for the USA.

It was the 1950s and postwar Los Angeles was booming. Upon settling here, Gutiérrez and his wife, Yolanda, whom he had married around 1960, had four other children in addition to Rodríguez: Rebecca, Manuel, Andrea and Antonio Jr., the last of whom died in 1990 in a car accident. .

Gutiérrez learned English while working in restaurants, serving as a busboy, dishwasher and waiter, said his daughter Rebecca Gutiérrez. Among his stops was the famous Perino's on Wilshire Boulevard.

But even after landing his preferred job in the Warner Bros. economy in the 1960s, Gutiérrez didn't slow down. After working in the studio each day, he would come home, eat something, take a nap, and head to his second job at Chianti Ristorante, a venerable Italian spot on Melrose. His time in Chianti was an education, Rebecca said.

“He learned a lot: he learned about wine, how to make a Caesar salad,” she said. “And he learned a lot from talking to people.”

Antonio's opened in 1970 and received brief notices in The Times and the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, the latter praising the decor as “warm and extremely intimate, with deep leather booths and authentic Mexican paintings.”

Gutierrez, sporting a meticulously trimmed mustache, moved gracefully through a restaurant of carved wood, painted tiles and curved arches. At first, he wore a colorful bolero vest and a big tie with a bow. Later, at Rodriguez's urging, he changed into a more conventional suit and tie.

Times columnist Gustavo Arellano, author of “Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America,” said menu items like Chicken In Pipian spoke of Gutiérrez's pride and confidence.

“If you open a Mexican restaurant on Melrose in the 1970s, you're basically looking at the past and the future of Mexican food in Los Angeles,” he said. “You know you have to include the mixed dishes, which still dominated Mexican restaurants at that time. But it is also seen that the Los Angeles palate demands more 'authentic' flavors. The fact that you are doing pipian “It shows that you are very proud of your food and that you know your Westside audience will love it.”

In fact, although Gutierrez was a pioneer, he still catered to the old-school American palate with comforting combo plates, like Yolanda's special, which included an enchilada, a chile Relleno, and a taco.

By the late 1980s, other Mexican restaurants had caught up with Antonio's. Places like La Serenata de Garibaldi were helping to expand Angelenos' conception of Mexican cuisine. Even so, the clients stayed at Antonio's house.

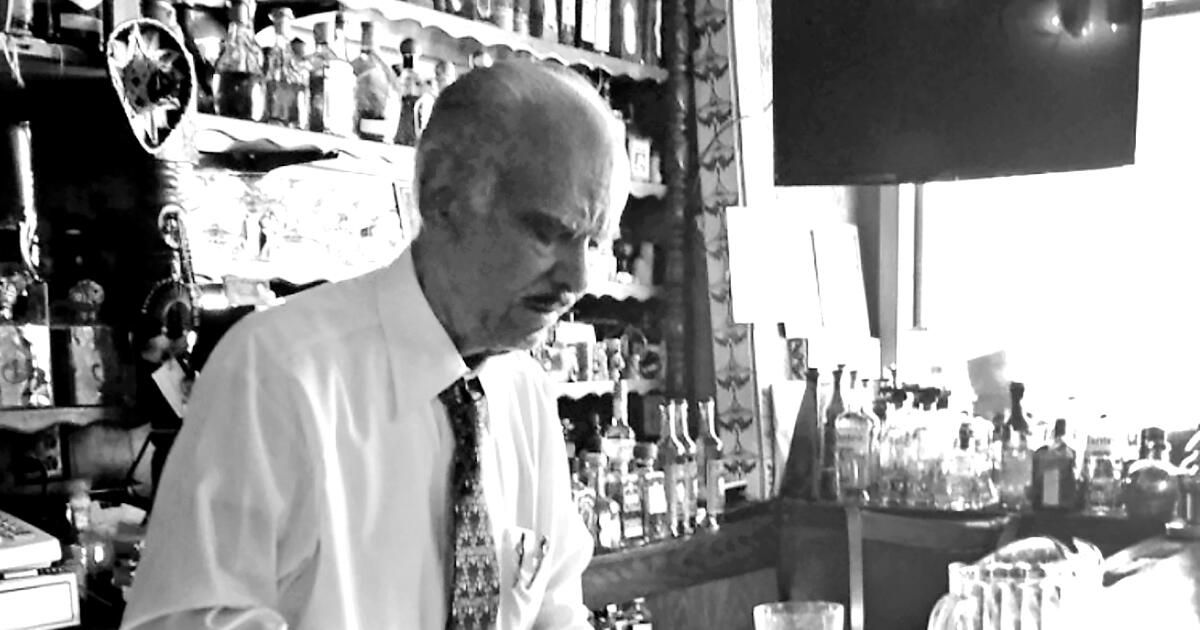

Antonio Gutiérrez at his Melrose Avenue restaurant around 2013.

(Courtesy of Irma Rodríguez)

But the pandemic and Gutiérrez's poor health proved to be insurmountable challenges. The social justice protests of May and June 2020, which occurred immediately after Los Angeles County restaurants reopened for in-person dining just days earlier, roiled the stretch of Melrose that included Antonio's. In the midst of the chaos there was significant material damage. Things became dangerous at Antonio's house, said Rodríguez, who worked there for a long time.

“My husband and son protected the restaurant for two days straight until the armed guards arrived,” said Rodríguez, whose husband, Guillermo, ran the restaurant with her. “He was crazy.”

He said the pandemic made it “very difficult towards the end to move forward.” And, she said, “the streets were changing; on Melrose, things got a little chaotic.”

Antonio's closed in January 2022 with little fanfare. But an article in the Beverly Press said that with the closure, Los Angeles had not only lost a good Mexican restaurant, but also “lost a part of its friendliness.”

And that emanated from Gutiérrez. Even though he had slowed down in the 2010s, he was still able to muster up his trademark charm and mention a few names.

In a video posted on YouTube in 2013, Gutiérrez prepared a New York strip steak “the way Mr. Sinatra liked it” and almond chicken “Barbara Sinatra style.”

“Much better than a taco, anytime!” Gutiérrez said of the chicken in almond sauce. “But don't discriminate against tacos, that's why we are also famous. “Barbara also likes my tacos.”