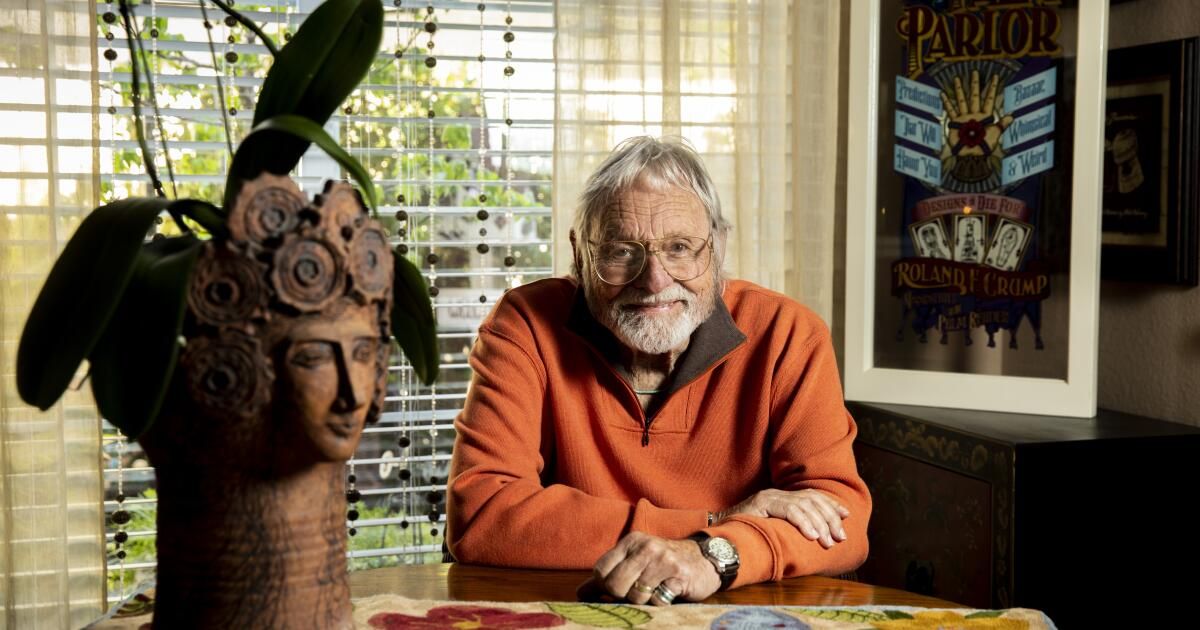

Rolly Crump had a huge reputation. A rebel in the Disney fold. A beatnik. An unapologetic “tell-it-as-you-know-what.”

Crump, who died last year at the age of 93, also forever changed the look of Disneyland. Her art can be found at Enchanted Tiki Room and, along with her close friend and fellow artist Mary Blair, at It's a Small World.

Crump's style possessed extraordinary flamboyance and circus volume, and caught the attention of Walt Disney, who pulled Crump out of animation and one day assigned him what would arguably become the most recognizable clock in Southern California. The clock is the anchor of the facade of Disneyland's It's a Small World.

Rolly Crump designed a poster for the West Hollywood folk club, Unicorn. The poster is part of a new exhibition dedicated to showcasing Crump's early work.

(From Christopher Crump)

This week, a variety of Crump's lesser-known personal works will go on display at the Song-Word Art House gallery in West Hollywood. The exhibit, called “The Lost Crump Exhibit,” is curated by Rolly’s son, Christopher, who followed in his father’s footsteps to work for Walt Disney Imagineering, the division of the company responsible for theme park design. “The Lost Exhibition” will draw heavily on Crump's work from the late '50s and early '60s, specifically his series of folk house-inspired rock 'n' roll-style posters.

The event is open to the public Friday through Sunday and the gallery is near the original location of one of Crump's old venues, the Unicorn Folk Club. A sign Crump drew for the venue will be the centerpiece of the exhibit. Christopher cites the free nature of the '50s folk scene as a major influence on his father's art, which had the kind of bold colors and intricate, line-heavy work one sees in a tattoo parlor.

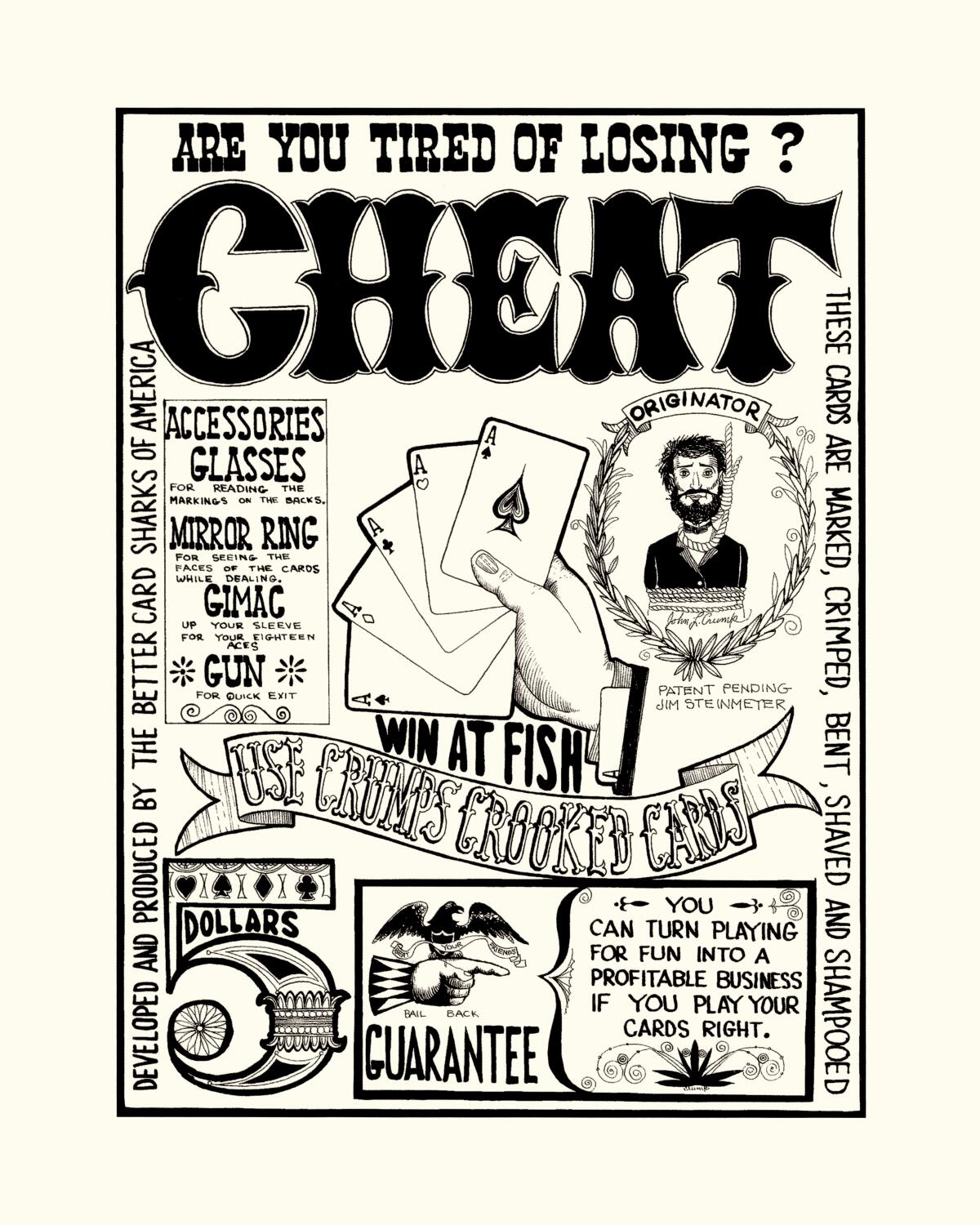

Other posters showcase Crump's acidic but silly sense of humor, such as what he called his “dopers,” that is, art that humorously celebrated drugs in the style of the bar posters of the Beat generation (“Be a man who dreams by itself,” says a painting encouraging opium).

Outside of his work at Disney, Crump continued to work in eccentric pop art throughout his career. A 1967 poster inspired by a comic strip by the psychedelic rock group West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. A copy will be displayed in Song-Word.

Crump remained at Disney until 1970, although he would return several times before retiring in 1996. He also designed an attraction for Knott's Berry Farm, briefly ran his own design firm, and had a short-lived store, Crump's, dedicated to his art. In 2017, Crump had a post-career exhibition at the Oceanside Museum of Art, but Christopher sees “The Lost Exhibition” as an opportunity to explore his father's lesser-known early work, before Crump worked on attractions like Haunted Mansion and It's a. Small World, the latter of which had its premiere at the 1964 World's Fair.

“This is personal for me,” Christopher says. “This is the exhibition that never happened. I should have done this. I should have had more gallery shows. The only real gallery stuff was when he had the Crump store on Ventura Boulevard, but he never had a formal show at the gallery.”

Christopher, who will be available all three days to share stories about his father, spoke to The Times about the program. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Rolly Crump at his store, Crump's, which, according to his son Christopher, was a short-lived operation on Ventura Boulevard.

(From Christopher Crump)

Your father started working for the Walt Disney Co. in 1952. You were born in 1954. This exhibition places special emphasis on works of art from that era. When did you first learn about your father's work?

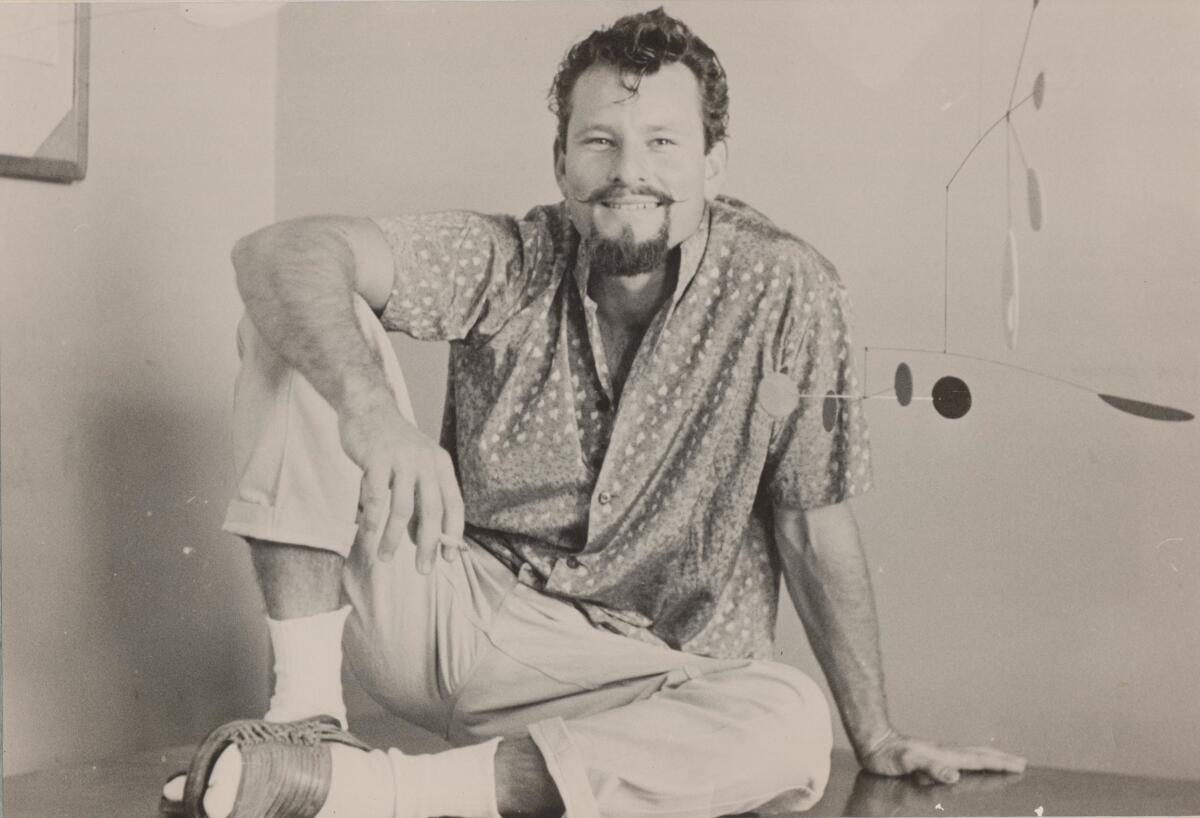

I was drawing all the time. He supported me as a model maker, I had a desk and tools and he bought me kits. I started building models when I was 6 years old. I saw him draw. But later, I recognized that he did this enormous work of his all the time. He went out with [animator-artist] Walter Peregoy a lot. Walter Peregoy got up at four in the morning and drew and painted. And that started to hit me. Dad had two jobs: he worked in animation and construction on the weekends, and he was removing all those artworks and mobiles. When someone calls themselves an artist, they have no choice. It is constant. It's all the time.

You also have to think about culture. Dad wasn't changing diapers, cooking, cleaning, washing and all that. Men didn't do that. It wasn't like there was anything wrong with him, but it wasn't until later when I said, “Hey, Dad, you have to help with the chores.” Whatever dad wanted to do, he would do it, so in dad's case, he would paint, draw, sculpt and make mobiles. I was going to continue to satisfy that itch of having to do those things.

And everyone would help. My mom painted a lot of my dad's things. He drew it and said, “Paint it red. Paint it green.” I remember painting paintings with colors, and this was in the early to mid 60's. We were all part of Dad's little art machine.

As you collect this poster, what impresses you today? What do you appreciate about the personal work you did while working in animation? I remember your dad saying he felt insecure as an entertainer.

A poster designed by Rolly Crump that is part of an exhibition of the artist's early work.

(From Christopher Crump)

These [animation] Artists: Walter Peregoy, Dale Barnhart, Frank Armitage and of course Ward Kimball and Marc Davis, all of these guys were amazing. Dad said, “I knew how to use a pencil.” He could draw, but had no formal education in the arts. These kids influenced him and he learned from them, but he needed to find his voice. I captured an interview recently (someone sent it to me) of him giving a talk, and Dad told this great story about his desire to learn to paint, to become an artist. I was trying to imitate Walt Peregoy's style and it didn't work. I was really frustrated.

He talked about going to an art exhibition at the studio and saw a piece of a group of gargoyles sitting on a log flying kites. And the light bulb went off. He said, “I can do that.” Dad has a quirky sense of humor and the animation world was all about making people laugh, so he went home and painted lobsters drinking martinis. And that was the first painting he did where he took the idea of telling a little story and making sure it was fun. That drove him.

What I've always loved about your father's personal work is that it has a fluid nature. You even see that on the Unicorn poster. It feels improvised, jazzy.

And what I think, and I heard him say this, he was always looking for something different and then giving it a twist. When you think about the folk era, when it was very hot, scorching hot, they were tramps on freighters writing songs about social injustice. They were people who “stick it to the man.” All of these things influenced him: the idea of popular music and freedom of expression.

Rolly Crump in 1957, when the artist was working in animation at Walt Disney Co.

(From Christopher Crump)

There was no way I could paint like those other guys. But he found his voice and these posters became more satirical. It is a kind of mocking but very ironic advertising. I'll be putting on a soundtrack of a lot of the music Dad had in his collection at home. So it's a four and a half hour compilation of Miles Davis, Nina Simone, Peter, Paul and Mary, Quincy Jones, Harry Belafonte, Wes Montgomery – all the stuff we listen to at home or that I listened to in his Porsche listening to the jazz station .

How do you connect what we'll see in this show to your best-known Disney work in It's a Small World or Enchanted Tiki Room?

Because he drew every day, his line work, his composition, and his technical skills as an artist improved. That led him to create things in the Tiki Room, the toys in Small World. He didn't wake up and get out of bed one morning and get really good. There was a gradual development of who he was. Then it reached a level of trust. He knew who he was and he made no apologies for it.

“The Lost Crump Exhibition”

He began to observe how Walt [Disney] He behaved well and found his rhythm with Walt. He waited a few years before he started getting stubborn, and then once Walt started listening to him, he annoyed all the other Imagineers. Everyone was singing and dancing. “Whatever Walt wants.” Rolly was not a dancer. How could this crazy beatnik character be Disney? It's like musicians. They are the chops. You mentioned the jazz thing: jazz is about improvisation. Jazz is about going with the flow and following your crazy ideas. Walt believed in Dad's crazy ideas.

And yet, those crazy ideas helped define the tone of Disneyland. Modern theme parks are very much aligned with the film and television aspect, however, there are many times in, say, It's a Small World, where it becomes very clear what Rolly's influence was.

My wife didn't know much about Disney. She rides It's a Small World, and my dad had been making birthday cards and Christmas cards, and she looked at It's a Small World and said, “Oh my God, that's my father-in-law.” And that's my thought. All of this was developed and worked out, and by the time the World's Fair came around and the '60s rolled around, he had spent a good eight or nine years tinkering around, and now he's flourishing. Now you have a scenario to work on.

So I'm talking about the '50s and early '60s before all that. What was it that happened to you that developed you and developed your confidence to be able to be that great guy?

It would be like in music. He played in many small clubs before hitting the big stages. My vibe is for people to remember how artists become what they become.