Françoise Hardy, the French chanson singer, songwriter, fashion “It Girl” and favorite of the French “yé-yé” pop movement of the 1960s, has died. She was 80 years old.

Her death was announced Tuesday on Instagram by her son, Thomas Dutronc, who wrote: “Maman est partie” (“Mom is gone” in French) without specifying when or where she died. Hardy said in 2004 that he had been diagnosed with lymphoma.

Hardy, a superstar in Paris by the time he turned 20, released his debut single, “Tous les Garçons et les Filles” (“All the Boys and Girls”), in 1962. Over the following decades, he released more than 30 Studio albums. , a job that was briefly interrupted by a retirement in the late 1980s.

Although not a household name in America (she sang most of her hits in her native language), Hardy was a phenomenon in her homeland, regarded as much for her minor-key lyricism as her delicate performance. She followed her first hit with “Le Temps de L'amour” (“The Time of Love”), which featured spacious, echoey production that captured the spirit of Gene Pitney's sessions with Phil Spector. Songs like “La Maison Où J'ai Grandi” (“The House Where I Grew Up”) and “Comment te Dire Adieu” (“How to Say Goodbye”) reflected on the absence of love and, once present, futility. to preserve it.

Director Roger Vadim, left, and stars Françoise Hardy and Jean Claude Brialy attend the premiere of “Château en Suède” (“Castle in Sweden”) in Paris on November 19, 1963.

(Max Micol / Associated Press)

“In music, I especially like slow, sad melodies that stir the knife in the wound. Not in a way that immerses, but in a way that uplifts,” Hardy said, according to Frédéric Quinonero's 2017 biography. “I still aspire to find the heartbreaking melody that will make me cry. A melody whose quality gives it a sacred dimension.”

Often dismissed as a performer at the time due to her gender and beauty (a 1967 Reuters article identified her as “the sexy, long-haired, mini-skirted French singing idol”), Hardy leveraged her skills as a writer and performer to make such thing was debatable. simplistic descriptions. Her appearance and charisma, however, did attract the attention of musicians such as Bob Dylan, Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, and French singer Jacques Dutronc.

In fact, many baby boomer music fans met Hardy not through a song, but by reading a Dylan poem on the back cover of his 1964 album, “Another Side of Bob Dylan,” where the seemingly lovelorn bard from Minnesota he wrote (in lowercase), “for françoise hardy / on the edge of the seine / a giant shadow / of notre dame / seeks to grab my foot / students of the sorbonne / whirling by on thin bicycles…”

Hardy parlayed her success as a singer-songwriter in the early 1960s into becoming a renowned fashion icon, astrologer, and published author. She also appeared in several films, including “Château en Suède” (1963), “What's New Pussycat?” (1965) and “Grand Prix” (1966). As the decades passed, her muse moved away from the commercially driven yé-yé sound toward psychedelia, folk-rock, and meditative, pop-centric adult pop.

“From the time he was 18, he knew he was different,” producer Erick Benzi, who collaborated with Hardy for two decades, told Uncut in 2018. “He was able to appear in front of great artists like Charles Aznavour and say: 'Your song is shit, I don't want to sing it.' “She never made concessions.”

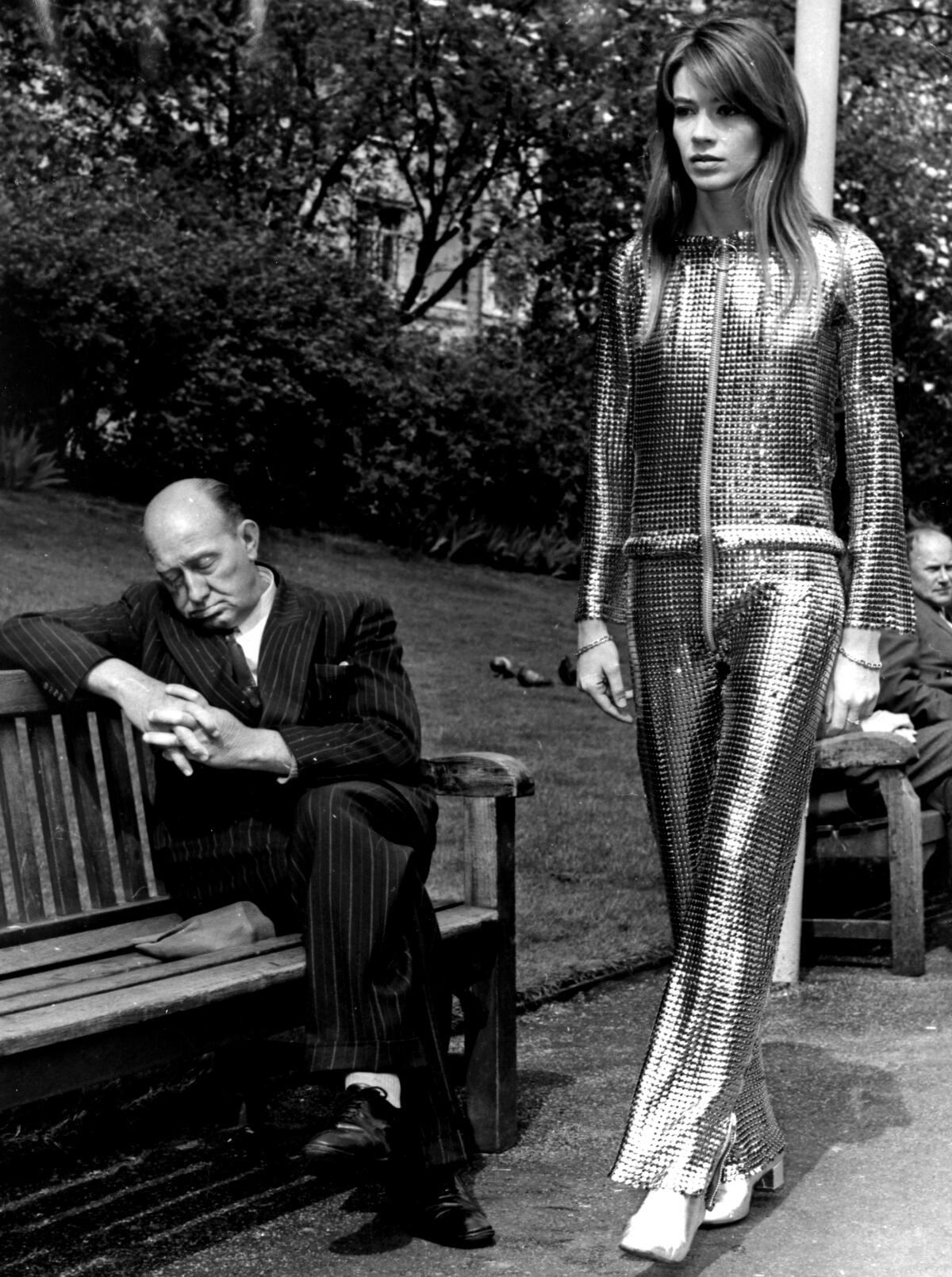

Françoise Hardy walks through a garden in London in 1968.

(Harris/Associated Press)

Born on January 17, 1944, during an air raid amid the final months of the German occupation of France during World War II, Hardy was conceived through an affair between her mother and a much older, well-to-do married man. Her only sibling, Sister Michele, arrived a year later.

Despite excelling in school and having a father of higher social status, Hardy faced an adulthood similar to that of his middle-class peers. At one point in her adolescence, she recalled in her 2008 memoir, “Monkey Despair and Other Trifles” (published in the US in 2018), “my mother and I conjured up all the realistic careers that were offered to me: executive secretary, medical secretary, nurse, pharmacist.” And she added: “I was secretly nursing an ambition to find an activity that had some connections to the style of music I had recently fallen in love with.”

As a teenager, as a reward for his academic success, Hardy's mother and father offered him a gift of his choice. He hesitated between a radio and a guitar before opting for the latter. “I'll never know why I chose a guitar, because all I ever wanted was a transistor radio,” he told The Guardian. “My future life would emerge from this crucial choice because, once I had this precious instrument in my hands, I began to scratch three chords over which I sang fragments of my own melodies.”

Alongside peers such as Jane Birkin, Brigitte Bardot, France Gall and Sylvie Vartan, Hardy rose to become a yé-yé hitmaker in her native Paris, attracting the attention of jet-setting pop stars, tastemakers and fashion lovers from London, New York and Tokyo. As with other yé-yé singers, Hardy's music blended mid-1960s bubblegum pop, groovy guitar lines, and the romantic tradition of French chanson to create sweet, sticky love songs.

Hardy first visited Los Angeles in 1968 to record his English-language album “En Anglais” (“In English”), although he had appeared on screen at the Cinerama Dome two years earlier in the racing car film “Grand Prix.” John Frankenheimer, but he never seemed too concerned about success in America. It didn't help that he suffered from stage fright.

James Garner and Françoise Hardy talk on the set of “Grand Prix” in 1966.

(Keystone-France / Gamma-Keystone / Getty Images)

Her imposing presence caught the attention of the Parisian fashion scene and she became a muse for designers such as André Courrèges, Emmanuelle Khanh and Yves Saint Laurent. Louis Vuitton's current creative director, Nicolas Ghesquière, called Hardy “the very essence of French style,” a trait evident in the cover photographs of Hardy's first four albums, which were taken by the fashion photographer (and then boyfriend) Jean-Marie Périer.

“My songs had little interest compared to Anglo-Saxon production. So I took it very seriously to dress well every time I went to London or New York,” she told Vanity Fair in 2018, calling herself “above all a fashion ambassador.”

In the late 1960s, Hardy and Jacques Dutronc began a relationship that would last the rest of their lives. His son, Thomas Dutronc, now a successful French singer, was born in 1973 and Hardy raised him while he continued to release some of his longest-running albums. The title track from '73's “Message Personnel” is a gentle exploration of unrequited love and unspoken emotions lush with orchestral arrangements.

Hardy and Dutronc married in 1981 (purely for tax reasons, both emphasized), but separated in 1988. Despite entering into other relationships, they never divorced and remained close. His extensive family life had its share of tragedy. According to Hardy's memoirs, in 1981 his father, with whom he had had little contact, was murdered in his home by a prostitute. As he also conveyed in his memoir, his sister, who had long struggled with mental illness, died in the mid-2000s. Although the police investigation never officially confirmed the cause, Hardy believed his sister committed suicide.

Commercial success provided Hardy the opportunity and time to fully explore his creativity; one main avenue was astrology. Introduced to the belief system in the 1960s, she immersed herself in the various schools of thought and eventually studied under the French writer Jean-Pierre Nicola. Using her fame to defend her methods, she eventually became the daily horoscope reader on Radio Monte Carlo. She published her astrology book “Les Rythmes du Zodiaque” (“Rhythms of the Zodiac”) in 2003.

Hardy published her first work of fiction, “L'Amour Fou” (“Crazy Love”) in 2012. Written as a companion to an album of the same name, its success kept her writing. Two books of essays followed in 2015 and 2016.

Hardy's statements on politics drew the ire of French liberals in 2012 when he claimed that if Socialist Party candidate François Hollande could initiate his proposed 75% tax on millionaires, Hardy “would have to sell my apartment”, and added: “I will be in the street.”

Hardy lived long enough to see his recordings rediscovered by a new generation of listeners. He sang on a remix of Britpop band Blur's 1994 song, “To the End,” and continued to release albums and collaborate with others for the rest of his life. In 2015, the respected archive label Light in the Attic reissued her first four albums. In 2021, Hardy and French house group Bon Entendeur released an updated version of her first hit “Le Temps de L'amour.”

“Nobody can sing like Françoise,” Iggy Pop said in 1997 while he and Hardy were promoting their version of “I'll Be Seeing You.” “Her emotional and musical precision combined with her sense of reserve and mystique create an indelible and very French impact on the listener. There’s no one that good around here.”

Singer Eddy Mitchell and Françoise Hardy appear together in Paris in 2008.

(Michael Sawyer / Associated Press)

“It's always been a big surprise to me that people, even very good musicians, were moved by my voice,” Hardy told The Guardian. “I know its limitations, I always have known them. But I have chosen carefully. What a person sings is an expression of who they are. Luckily for me, the most beautiful songs are not happy songs. The songs we remember are sad and romantic songs.”

Hardy, who survived lymphatic cancer in the mid-2000s, was diagnosed with a malignant tumor in her ear in 2018. That same year, she explained her situation in an email to the French magazine Femme Actuelle: “My physical suffering It's already been so big. “It is terrible that I am afraid that death will force me into even more physical suffering.”

Arguing for his right to die, he wrote: “It is not up to doctors to grant every request, but rather to shorten the unnecessary suffering of an incurable disease from the moment it becomes unbearable.”

For an artist long drawn to the ways people cope with pain and sadness, her situation seemed aligned with the themes of her music.

“I sing about death in a very symbolic and even positive way. There is acceptance there too,” he told The Guardian. “At my age, I can only sing about that special train that will take me out of this world. But, of course, I also hope that it will send me to the stars and help me uncover the mystery of the cosmos.”

Hardy is survived by her husband and son.