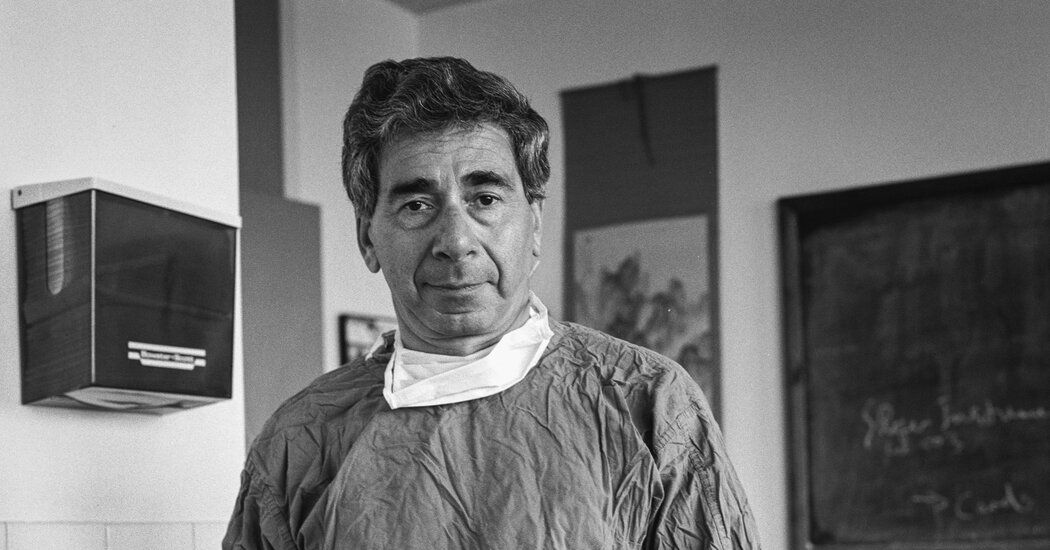

Roy Calne, a British surgeon whose work in organ transplants helped turn what was once considered impossible into a procedure that saved the lives of millions of people around the world, died Jan. 6 at a nursing home in Cambridge. , England. He was 93 years old.

His son Russell Calne said he died of heart failure.

There are innovative surgeons and researchers, but very few people are both. Dr. Calne (pronounced “kahn”) was an exception: he developed and practiced many of the operative techniques involved in transplantation, while at the same time working to identify which medications would cause the body to accept a new organ.

The son of a suburban London car mechanic, Dr. Calne had long wondered why damaged organs, such as faulty carburetors, could not be replaced with new ones. But when he was a student in the early 1950s, he was repeatedly told that could never be done.

However, he persevered, doing research in his spare time as an instructor of anatomy at the University of Oxford and later as a professor and first chair of the department of surgery at the University of Cambridge.

It was difficult. Often working with pigs and dogs, almost all of which died shortly after surgery, Dr. Calne drew the ire of animal rights advocates. Someone (I suspected he was an activist) once left a bomb on the doorstep of his house; Dr. Calne called the authorities, who safely detonated it.

At first, he used whole-body radiation to suppress the immune response, a procedure that killed virtually all of his subjects, including some humans. He eventually switched to medication, starting with an anti-leukemia drug called 6-mercaptopurine.

He performed the first successful liver transplant in Europe in 1968, a year after Thomas E. Starzl, a surgeon from the United States, completed the first such procedure in the world.

Still, organ transplantation remained rare and dangerous. Then, in the early 1970s, Dr. Calne learned of a new drug, cyclosporine. He and his team began testing its immunosuppressive applications and realized that the drug could be the affordable and effective solution they had been looking for.

The one-year survival rate for kidney transplants rapidly increased from 50 to 80 percent, and by the mid-1980s the number of hospitals worldwide offering transplant surgery had grown from a few dozen to more than 1,000.

Dr. Calne continued to hone his craft and achieve surgical milestones. In 1986, working with his fellow surgeon, John Wallwork, he performed the world's first liver, heart and lung transplant on the same patient. In 1994 he performed the world's first six-organ transplant, replacing a patient's stomach, small intestine, duodenum, pancreas, liver and kidney in a single operation.

In 2012, he and Dr. Starzl shared the Lasker Prize, the most prestigious prize in medicine after the Nobel Prize.

When asked by The New York Times that year if he expected to also receive the Nobel, Dr. Calne responded: “I have a patient and it's been 38 years since his transplant. He just returned from a 150 mile bike ride through the mountains. That is my reward.”

Roy Yorke Calne was born on 30 December 1930 in Richmond, a suburb about 10 miles west of London, to Eileen (Gubbay) and Joseph Calne.

Roy entered Guy's Hospital, part of the medical school at King's College London, in 1946. Most of his classmates were service members returning from World War II and many were a decade older than him.

Halfway through his studies he was assigned the task of caring for a young patient who was dying from kidney failure. When the patient asked why he couldn't just receive a new kidney, Dr. Calne recalled, senior doctors laughed at him.

“Well, I've always disliked being told that something can't be done,” he told The Times in 2012.

He graduated in 1952 and then served three years in the army, primarily in Southeast Asia, where British colonial forces were waging a guerrilla war in present-day Malaysia.

He married Patricia Whelan in 1956. Along with his son Russell, she survives him, as does another son, Richard; his daughters, Jane Calne, Debbie Chittenden, Suzie Calne and Sarah Nicholson; s13 grandchildren; and his brother Donald, a leading expert on Parkinson's disease.

Dr Calne returned to Britain in 1956. He held a series of short-term teaching positions while he returned to his medical training and began his own transplant research.

After Oxford, he worked as a doctor at the Royal Free Hospital and received a fellowship at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (now part of Brigham and Women's Hospital) in Boston, where the first successful kidney transplant was performed in 1954.

In 1965, Dr Calne became a professor at Cambridge. He remained there until 1998, when he assumed emeritus status. After retiring, he devoted more time to his other lifelong passion, painting.

He often painted his patients (with their consent) and in 1988 took lessons from one of them, the Scottish painter John Bellany.

Dr. Calne may have been an amateur, but his paintings were widely praised by critics. In 1991, the Barbican Center in London mounted an exhibition of his work, titled “The Gift of Life.”