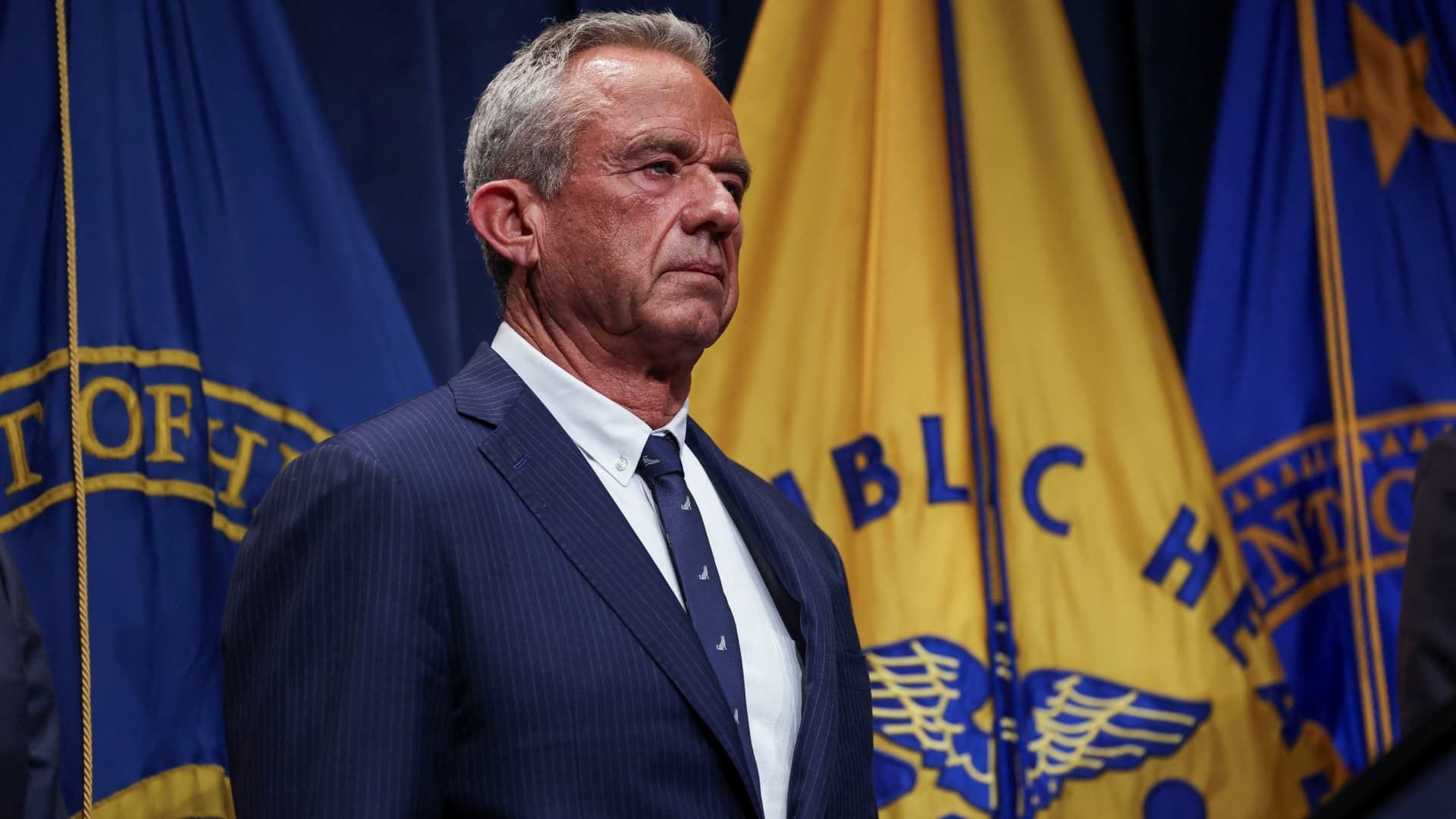

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s hand-picked vaccine committee on Thursday postponed crucial votes on hepatitis B vaccines for infants until Friday, saying it will give members more time to review proposed language on the measure.

One panel member, Dr. Cody Meissner, a professor of pediatrics at Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine, made a motion to postpone the vote because of confusion among the group over the language.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends that all babies be vaccinated against hepatitis B within 24 hours of birth.

It is unclear whether the panel, called the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, could significantly delay or eliminate the so-called birth dose of the vaccine for babies whose mothers test negative for the virus. The group introduced a vote on the vaccine in September because some members first asked for a more robust discussion.

But any changes could have far-reaching consequences: Some public health experts say vaccinating fewer newborns against the virus could lead to a rise in chronic infections among children.

Hepatitis B, which can be passed from mother to baby during childbirth, can cause liver disease and premature death. There is no cure.

“We have a vaccine that is very effective at preventing an incurable disease. We should make the most of it,” Neil Maniar, a public health professor at Northeastern University, told CNBC.

The birth dose recommendation was introduced in 1991 and has since been credited with reducing infections in children by 99%. Maniar called this a “remarkable success story that we risk reversing” if the committee changes the recommendation.

The panel's decisions are not legally binding, as it is up to states to mandate vaccines. But the ACIP recommendations have important implications for whether private insurance plans and government assistance programs cover vaccines at no cost to eligible children.

The panel's upcoming two-day meeting in Atlanta comes after Kennedy earlier this year gutted the committee and named 12 new members, including some well-known vaccine critics. During the September meeting, some advisers raised questions about whether the shot's benefits outweigh the potential safety risks.

But the vaccine is “an incredibly safe vaccine with minimal risks,” Dr. Sean O'Leary, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics' Committee on Infectious Diseases, said during a news conference Tuesday.

“I've never really seen a fever associated with the hepatitis B vaccine,” said O'Leary, who practiced for eight years as a general pediatrician and worked in a newborn nursery.

The AAP, which publishes its own vaccine schedule, continues to recommend the universal birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine because it “saves lives,” he added.

A new review, published Tuesday, of more than 400 studies spanning four decades also found no evidence that delaying the birth dose of the universal hepatitis B vaccine improves safety or effectiveness. The review also found that the birth dose does not cause serious adverse events or deaths in the short or long term.

A 2024 CDC study showed that the current vaccination schedule has helped prevent more than 6 million hepatitis B infections and nearly 1 million hepatitis B-related hospitalizations.

Merck and GSK make hepatitis B vaccines that are used from birth. None of the vaccines generate significant revenue for the companies.

But John Grabenstein, a former Merck vaccine executive and military pharmacist, said a change in the recommendation could lead to disruptions in vaccine supplies for companies.

“They have built up their reserves and are doing extensive calculations to be able to comply with the status quo,” Grabenstein, who no longer has financial ties to Merck, told CNBC. “If the status quo is altered without warning, then there would be too many things and not enough, which could easily create one-time shortages.”

Still, he said his first concern from a public health standpoint is that fewer children will be vaccinated in time, leaving them vulnerable to infection.

Merck, during the panel's September meeting, also declined to change the recommendation.

“Reconsidering vaccination of newborns against hepatitis B according to the established schedule poses a serious risk to the health of children and the public, which could lead to a resurgence of preventable infectious diseases,” Dr. Richard Haupt, Merck's head of global medical and scientific affairs for vaccines and infectious diseases, said at the time.