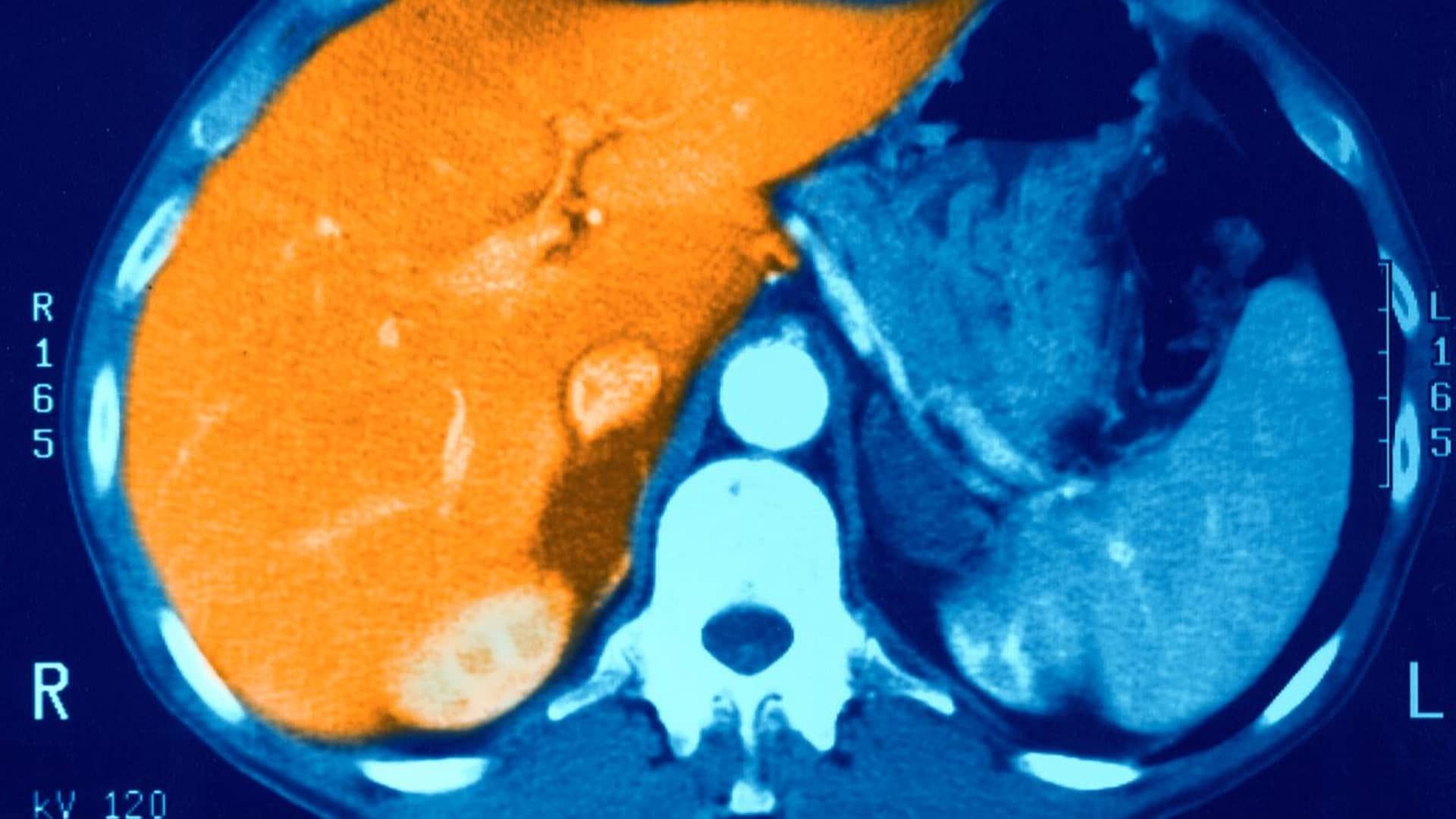

Image of a healthy liver not ravaged by fatty liver disease.

BSIP | fake images

Do you think a friend or colleague should receive this newsletter? Share this link with them to register.

Good afternoon! Drug makers aren't just racing to develop drugs to treat obesity. They are also racing to expand the uses of those weight-loss treatments, including for a severe form of liver disease.

Some drug manufacturers – including dominant market players, Nordisk and Eli Lilly – they already have demonstrated the drugs' ability to help patients lose unwanted pounds and regulate blood sugar.

Now their goal is to demonstrate that treatments can provide additional health benefits. Doing so could drive even more revenue from the booming market and expand limited insurance coverage for those treatments, most of which cost about $1,000 a month.

Competition intensified Monday after Denmark-based drugmaker Zealand Pharma and its partner Boehringer Ingelheim published strong results from a mid-stage trial testing their drug, survodutide, in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, or MASH. That condition is characterized by excessive fat accumulation and inflammation in the liver and can lead to liver scarring or fibrosis.

Survodutide, which helped overweight or obese patients lose up to 19% of their weight in another Phase 2 trial, is just one of a long list of drugs that could eventually become treatments for MASH.

A Monday update to STAT's obesity drug tracker shows that at least 23 (or about a fifth) of the 105 weight-loss drugs in development or on the market are also being investigated for their ability to treat the condition. .

So why are drug makers focusing on this specific form of liver disease? For one thing, there are no approved medications to directly target MASH. The drugs being tested may not cure the condition, but their reach could be large: around 115 million people worldwide are affected by MASH, and it is estimated that between 3% and 5% of American adults suffer from the condition, according to some studies.

The new data underscore the potential for weight-loss medications to help. According to Zealand Pharma, up to 83% of trial participants treated with survodutide experienced significant improvements in their disease without worsening liver scarring after 48 weeks, compared to 18.2% in a group receiving a placebo.

Survodutide also met one of the trial's second goals, which was to show a “statistically significant” improvement in liver healing. There were also no unexpected safety or tolerability issues among those who received the drug, even at higher doses.

Mayank Mamtani, an analyst at Riley Securities, said the data “materially exceeded investor expectations” and even appears to improve on the mid-stage testing data that Eli Lilly released earlier this month.

About 74% of patients who received the highest dose of Eli Lilly's drug, tirzepatide, became free of MASH without worsening liver scarring after one year. That compares with about 13% of those who received a placebo.

It was less clear to what extent this drug reduced liver scarring, which was the second objective of the trial. Eli Lilly did not disclose whether tirzepatide met that goal, but the company said the drug's effect on scar reduction was “clinically significant” at all dose sizes.

However, Jefferies analysts cautioned in a note on Monday that the Eli Lilly trial included patients with more severe forms of liver scarring compared to the Zealand Pharma study. That may explain the differences in the data.

The two medications work differently. Zealand Pharma's treatment mimics a gut hormone called GLP-1, which suppresses appetite, but it also mimics another hormone called glucagon. Meanwhile, Lilly's tirzepatide targets GLP-1 and a different hormone called GIP.

It is too early to say whether one drug is better than another for treating MASH. It will probably be years before we see drugs from Eli Lilly and Zealand Pharma on the market as therapy for fatty liver disease.

Boehringer Ingelheim told Reuters on Monday that the company expects survodutide to be launched as a treatment for MASH or obesity in 2027 or 2028, depending on favorable trial data.

Full results from Eli Lilly and Zealand Pharma's mid-phase trials will be presented at a medical conference this year. We also have to wait for data from other drugmakers: Novo Nordisk is studying semaglutide, also known as Wegovy for weight loss and Ozempic for diabetes, in a late-stage trial for the treatment of MASH.

But a biotech company may be the first to bring a successful MASH drug to market: The Food and Drug Administration must decide whether to approve a drug called resmetirom from Madrigal Pharmaceuticals on March 14.

The latest in health technology

Change Healthcare outage reaches seventh day after cyber attack

Traders work at the booth where UnitedHealth Group is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Brendan McDermid | Reuters

It's been a tough week for Change Healthcare.

The company, which offers solutions for payment and revenue cycle management, said its systems are down for the seventh consecutive day after the parent company UnitedHealth Group revealed that a cybersecurity threat actor “suspected of being associated with a nation-state” gained access to part of its information technology network last week.

The scope and nature of the breach is unknown, but UnitedHealth said it isolated and took the affected systems offline “immediately upon detection” of the threat, according to a filing Thursday with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

The company did not disclose exactly which Change Healthcare systems the attack disrupted, but the breach has caused problems for health systems and pharmacies at companies like CVS Health and Walgreens.

UnitedHealth told CNBC late Monday that more than 90% of all U.S. pharmacies have implemented modified workarounds for electronic claims processing to mitigate the impact of the disruption, while the remaining pharmacies have implemented workarounds. out of line.

For consumers like Cary Brazeman, the disruption has been a headache.

Brazerman attempted to pick up a prescription at a Vons pharmacy in Palm Springs, California, on Saturday, but was told the pharmacy had not received the transmission from his doctor. Even if the location had, employees said they wouldn't have been able to get his insurance.

“I thought, 'Okay, what am I supposed to do now?' and they say, 'We don't know,'” Brazerman told CNBC in an interview.

On Monday, Brazerman said the pharmacy had set up a solution that helped it communicate with some insurance companies, but not all. He said he plans to go back to see his doctor to pick up a printout of his prescription, take it to the pharmacy and hope for the best.

His immediate concern is not whether his information was compromised, he said, but whether people who really need medication can access it. Especially patients who have more serious conditions than yours.

“I'm mobile so I can make these rounds if I need to and I can pay cash if I need to, but there are a lot of people who can't,” he said.

Feel free to send tips, suggestions, story ideas, and facts to Annika at [email protected] and Ashley at [email protected].