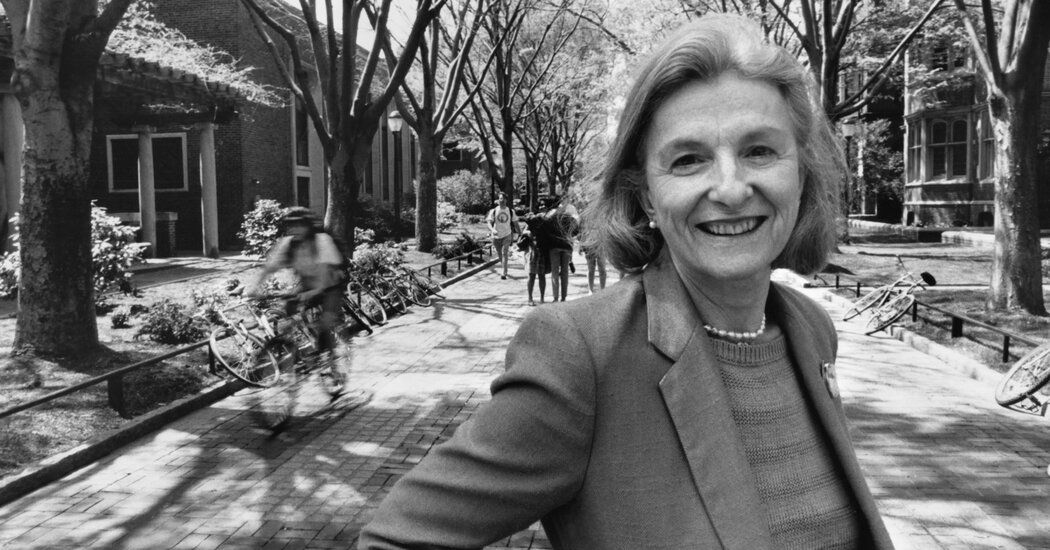

Claire M. Fagin, a leading expert, advocate and change agent in the nursing profession, and one of the first women to lead an Ivy League university, the University of Pennsylvania, died Tuesday at her home in Manhattan. She was 97 years old.

His death was confirmed by his son and only immediate survivor, Charles.

Among other accomplishments, Dr. Fagin is widely credited with reversing the common practice of strictly limiting parental visits to hospitalized children. She was inspired (and enraged) by what happened in the early 1960s, when she and her husband were visiting her young son Joshua, hospitalized for hernia surgery: They were ordered out of the hospital. .

So when he earned his doctorate in nursing from New York University in 1964, he made the practice of limiting visitors the topic of his thesis research. Her findings that the practice was harmful attracted widespread attention (she was interviewed on television about it) and initiated a transformation in medical care.

“She was the one who solved that,” said Linda H. Aiken, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, where Dr. Fagin was named dean in 1977.

Dr. Fagin transformed the school: tripling its enrollment, establishing a doctoral program in nursing, and turning Penn into a widely recognized world leader in nursing research and education. In 2006, Penn renamed its Nursing Education Building the Claire M. Fagin Nursing Sciences Building.

“It's really difficult to identify someone who has had a greater impact on nursing than Claire,” Dr. Aiken said.

In 1993, when Penn President Sheldon Hackney left office to become president of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Dr. Fagin replaced him as acting president, a position she held until 1994 (she is often credited with being the first woman to hold the position). she president of an Ivy League university, although Hanna Holborn Gray was acting president of Yale from May 1977 to June 1978).

Dr. Fagin later served as founding director of the John A. Hartford Foundation's national geriatric nursing program. She also served as chair of the advisory board that converted a $100 million grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation into the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at the University of California, Davis, which focuses on master's and doctoral programs in nursing. .

Meanwhile, she worked to earn nurses the professional respect she felt they did not always receive and the autonomy they needed to work in new ways, for example as nurse practitioners or researchers. She also advocated for baccalaureate programs for training registered nurses, as opposed to the two-year hospital-based or associate degree training programs that were once common.

In an interview for this obituary in 2003, Dr. Fagin said, “It's bad for nursing to not be able to differentiate professional nurses from people who go to school for two years.” (According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, a bachelor's degree is now the “typical” entry-level requirement for registered nurses.)

Before joining Penn, Dr. Fagin was chair of the department of nursing at Lehman College of the City University of New York and director of its Institute of Health Professions, as well as director of graduate programs in psychiatric nursing in the division of nursing education of New York. University. When the National Institute of Mental Health established a clinical research center in 1953, she was its first director of children's programs. She was a member of the National Academy of Medicine.

Claire Muriel Mintzer was born in Manhattan on November 25, 1926, the daughter of Harry Mintzer, an immigrant from Russia, and Mae (Slatin) Mintzer, from Poland. She grew up in the University Heights section of the Bronx, where her parents owned a grocery store.

He entered Hunter College at age 16; Despite the objections of her parents, who hoped she would emulate an aunt and become a doctor, she enrolled after one semester at Wagner College on Staten Island, which she chose because it had just established a bachelor's degree program in nursing.

His parents opposed his decision, until his aunt pointed out that he could always enroll in medical school after earning his degree.

But medical school wasn't something she wanted, she said in the interview. Instead, she said, she was inspired by the idea of wartime nursing service. And she, she added, not entirely jokingly, admired the glamorous blue, red-lined capes worn by members of the Army Nurse Corps.

By the time she earned her nursing degree in 1948, she had already begun working at Seaview Hospital on Staten Island, which was then a tuberculosis hospital. Her work with children there developed into a lifelong interest in children's psychiatric problems and in psychiatric nursing in general. From there she went to Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan, where she worked with emotionally disturbed adolescents.

After earning a master's degree in psychiatric nursing from Columbia University in 1951, Dr. Fagin joined the pediatric psychiatry staff at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.

While working there, she met Samuel L. Fagin, a mathematician and electrical engineer, and they married in 1952. He died in 2019 at age 96. Her son Joshua died of Covid in 2020 at age 62.

Well into her 90s, Dr. Fagin continued to write and speak about the importance of the nursing profession, as well as its problems and how to address them. In 2022, when there was widespread concern about Covid-related burnout among healthcare workers, particularly hospital nurses, she and Dr. Aiken published an analysis in STAT, an online magazine covering health, science and medicine, suggesting that the real cause of the burnout was a lack of hospital staff, something they said Medicare could fix by increasing existing hospital staffing requirements.

When Dr. Fagin died, she and Dr. Aiken were working to find better ways to encourage nurses, doctors and other health care workers to speak as one on public health issues.

Nursing is “a Renaissance vocation,” Dr. Fagin maintained. “Healing is an art. You are using a science to make an art.”

Despite her advanced degrees, her prominent academic positions, and her honorary degrees and other awards, Dr. Fagin always strove to identify herself as a nurse, a practice, she recalled, that did not sit well with her mother. Citing her other qualifications and the jobs she held, her mother said that her daughter was not, as she put it, “a real nurse.”

“I was like, 'Mom, I'm a registered nurse,'” Dr. Fagin said. “That's what it means: real nurse.”

Cornelia Dean is a science writer and former science editor of The New York Times. His latest book is “Making Sense of Science.”