It was just 25 years ago that “The Sopranos” debuted on HBO and reset the clock on what some like to call the Platinum Age of television.

Alex Gibney’s two-part documentary, “Wise Guy: David Chase and the Sopranos,” premiering Saturday, again on HBO, is, among other things, a kind of triple profile of creator Chase, star James Gandolfini and their mutual creation, New Jersey’s “waste management consultant” — that is, mobster Tony Soprano. In that “Sopranos” knowledge, its premise and characters taken for granted, it’s not a film for beginners. But it should appeal to anyone interested in the inspirations, decisions, revisions, sweat and serendipity that go into making a series so critically lauded that “Saturday Night Live” parodied the reviews (“‘The Sopranos’ will one day replace oxygen as what we breathe to stay alive”).

What made “The Sopranos” unique, if not unique, was the amount of freedom it was given. It was not the first creator-driven series — “Ozzie & Harriet,” written and directed by star Ozzie Nelson, preceded it by 47 years — and “The Larry Sanders Show,” HBO’s first major series, was largely a pure expression of Garry Shandling’s vision. But its massive success undoubtedly empowered future showrunners and shaped conversations in executive offices. It opened the door to similar series that might otherwise never have been proposed or greenlit — “Ozark,” “Animal Kingdom,” “Breaking Bad” — and inspired a rage for antiheroes from which television has yet to recover.

The cast of season 1 of HBO's “The Sopranos.”

(Anthony Neste)

What also sets the show apart is that it’s personal. No Sopranos fan is unaware of the fact that Tony’s nightmare mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand), is based on Chase’s. (“Do I trust that this creature I’m playing is dead?” Marchand said.) Not only did the show borrow from Chase’s life (the Sopranos lived in one of the neighborhoods where Chase grew up), it asked the writers to tap into the darkest, weirdest parts of themselves and their pasts. Describing the writers’ room, Robin Green admits, “We could have been mistaken for racists, sexists, whatever.”

There are the usual elements that make making-of documentaries appealing, of which this one is a prime example: audition tapes, on-set movies, amusing anecdotes, historical photos and footage. Gibney’s idea of interviewing Chase in a replica of Dr. Melfi’s office from the series, putting himself in the therapist’s chair, is a little too obvious, perhaps, but not inappropriate for the reluctant but ultimately willing-to-talk subject. “I didn’t realize this was going to be about me,” Chase says, and “Seriously, I don’t know anything about this,” and soon, “I’m talking too much.” Other commentators, including actors Lorraine Bracco, Michael Imperioli, Drea de Matteo, Steven Van Zandt and Edie Falco, and HBO executives Chris Albrecht and Carolyn Strauss, describe a sometimes difficult, if much-admired, boss from the outside.

We also see Chase’s Stanford student-directed film, “The Rise and Fall of Bug Manousas,” in which gangsters in 1940s clothing sport long hair and 1970s mustaches—a 1970s student film, in other words. “We thought we were making Godard,” Chase relates. “I don’t know what we thought Godard was making, but we weren’t.” After working on some sub-Corman exploitation films, he made his way into television, where, though successful (he worked on “The Rockford Files,” “I’ll Fly Away” and “Northern Exposure”), he was dissatisfied: “The problem was that you knew what the limits were, but you were always testing them and always failing.”

When HBO picked up “The Sopranos,” he says, “it was like I’d been in the middle of a terrible ocean and landed on a desert island, a beautiful palm-colored island. I thought, My life is saved.” On the big screen, movies that put gangsters, and specifically Italian gangsters, at the center of the story were nothing new: “The Godfather,” “Goodfellas” and “Casino” had all been released. And “The Sopranos,” which began as a feature-length script, had cinematic ambitions.

The pilot, in which Tony, becoming depressed after a family of ducks living in his pool takes off, reluctantly sends him to therapy, was thrilling to me. I loved the idea that a villain might learn something about himself, that the kind of character normally presented as static might develop. Well, I was wrong. That never happened. (Therapy, Chase says, didn't make him a better man, just a better mobster.)

1

2

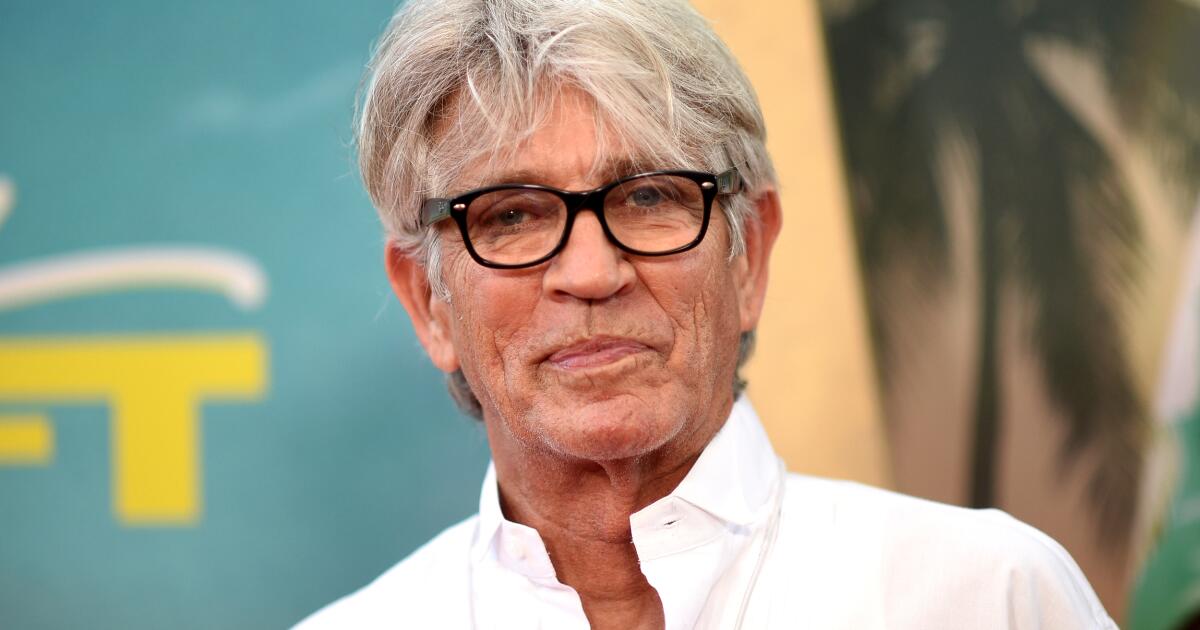

1. Steven Van Zandt was among several “Sopranos” cast members interviewed. (HBO) 2. Edie Falco in “Wise Guy: David Chase and The Sopranos.” (HBO)

Since most of us knew him as Tony Soprano before we ever met the actor, Gandolfini comes off almost surprisingly sweet. Much of the second episode is devoted to him, to the cost of living inside Tony, or Tony living inside him, and to the long hours the role required. “I came in with a big smile on my face and got punched in the nose,” he tells an interviewer. When he negotiated a $1 million-an-episode contract with HBO, he gave $30,000 checks to his castmates — aside from Falco, who seems to be hearing this story for the first time — but also agreed to have $100,000 docked for every day of work he missed, of which there were more than a few. Before assessing the infamous finale, Gibney moves on to the tribute to Gandolfini — he died in 2013 at age 51, six years after the series ended — and Chase’s moving eulogy.

Regardless of the show’s quality, Tony and his crew had me fed up some time before the finale, though I did watch it all the way to the end and the infamous moment when the screen went black as Tony stared at the door of the restaurant where he was meeting his family, a moment cinematographer Alik Sakharov calls “a resolution of irresolution.” Though Chase indicated at times that this was a death scene, it’s not a question he, or anyone else interviewed, wants to answer here. (Van Zandt has a de rigueur answer: “What happened was the director yelled ‘cut’ and the actors went home.”) Though Tony deserved his karmic comeuppance, I happily remain in that ambiguous space.

The show was widely discussed during its run and afterward, and there's probably little here that hasn't been expressed elsewhere. But this is a movie, and Gibney repeatedly juxtaposes the artists' lives with examples from the show. It may seem a bit simplistic, as it often does when discussing art in terms of life, but it's also quite persuasive. The analysis of the show, by Chase and others, is thorough, sometimes surprising (the staging of the finale was influenced by “2001: A Space Odyssey”) and sometimes poetic. You may not have grasped the significance of the lyric, “The movie never ends, it goes on and on and on and on,” from Journey's “Don't Stop Believin',” which plays during the final scene, but it illuminates that abrupt black screen.

“You may not move on,” Chase says, “but the universe will move on, the movie will move on.”