Two of the most elegant crime thrillers of the 1980s, “To Live and Die in Los Angeles” and “Manhunter” by Michael Mann, will be screened at the Egyptian Theater on Saturday as part of Beyond Fest. Actor William Petersen, who starred in both projects in his first film roles, will be there for a Q&A after each show.

In “To Live and die in la” 1985, Petersen plays Richard Chance, a secret service agent assigned to investigate a falsification ring in Los Angeles. He is looking for Rick Masters (Willem Dafoe), a amoral artist who has turned his talent for forging money. With an evocative cinematography by Robby Müller and Music by Wang Chung, the film is a propulsive portrait of Los Angeles in the 80s, with an exciting persecution through the lex and a car persecution now iconic that goes through the incorrect form on the highway of the terminal island around Long Beach.

For “Manhunter” of 1986, Petersen, Will Graham, a former FBI criminal profiler with an unusual capacity to understand the mentality of serial murderers. Although he retired, Graham is attracted to a new disconcerting case. A disturbing meditative adaptation of the 1981 novel by Thomas Harris “Red Dragon”, the film presents Brian Cox in the role of Hannibal Lecktor (enigmatically spelling differently here) five years before Anthony Hopkins Immortalized in “The silence of the lambs”.

Petersen, 72, was put by phone earlier this week to talk about the experience of making these two films in the period of one year, throwing it to a race that would include a long series in the popular series “CSI: investigation of the crime scene”.

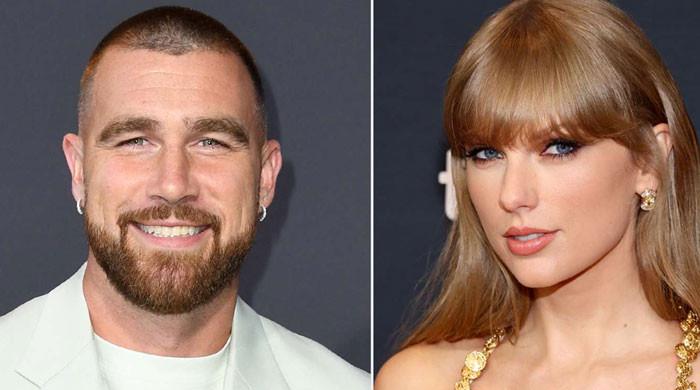

William Petersen and Darlanne Fuegel in the movie “Live and die in Los Angeles”

(Sunset Boulevard / Corbis through Getty Images)

[The following interview contains spoilers.]

These two films in particular – Friedkin's “Live and die in Los Angeles” and Mann's “Manhunter” – Now it seems essential crime Thrillers, Then it makes sense to show them together. How connected are theyHey for you?

They are really connected. I shot them both in the same year, and they were my first two photos, really. That was at a seminal moment for the American actors in Chicago. Suddenly we were suddenly brancing: I didn't even have an agent for those first two photos. I was doing deals with my business manager of my theater company, which became my producing partner, because we were only theater actors. In fact, when Billy [Friedkin] He offered me the role in “Live and die in la”. I had to call my friend John Malkovich, who had just made “the fields to kill”, because I had no idea what I was supposed to ask or get anything. He had no idea if he was supposed to win five hundred dollars per week or five thousand.

It would be one thing if I had started with a small indie somewhere with a new director or whatever. I learned a lot in that year from those two men and those projects. It was an incredible education for me. And I could continue to return and do the theater. Because it was never my intention to make movies, it was not as if I were looking for them. They just arrived and they found me.

I heard you say that before, that you feel you learned so much in that year making those two films. Can you boil that for a bit? What do you think you took those experiences?

They are such different filmmakers. Billy was all: running, assembling, improvising, stealing shots, we must not do this, let's do it anyway. And so it was almost like a documentary. It was as if we were really doing it. And then Michael is a craftsman that each part of everything is studied, controls and carefully attenuated. And for both of them to happen in a period of 12 months, consecutive, it took me a long time to process all that. I didn't know how much I was learning because I didn't have a frame of reference for any of that.

With “to live and die in la” in particular, there is so much energy in that film.. WDid that come from here?

[Friedkin] I wanted it. I wanted it to be like that. I think part of this was a call to “the French connection.” They were just trying to get shots and I think he felt that he really required energy like that. I remember that he told Robby Müller, our DP, a brilliant man, a wonderful man, he didn't care if we reached our marks. Robby had to discover how to capture this. Friedkin]said: “I just want them to react, I just want me to be. “Much of this was a kind of improvisation, both physically and textually.

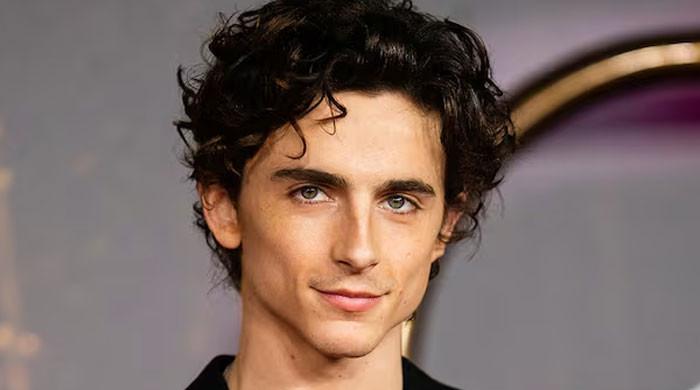

Petersen, on the left, and John Pankow in the movie “Live and die in Los Angeles.”

(Sunset Boulevard / Corbis through Getty Images)

There is a moment in the movie in which you have one of those Metal metal and start hitting it against the wall again and again until it finally opens. What was improvised?

We don't think the scene was going to take so far. It is configured as something true, and then at some point we stop and put the case of support, which will open. And we begin to film that scene and we only continue in it. Billy never cut it. I don't stop until I heard cut. And Billy knew. So I was hitting the thing, that's why [co-star John] Pankow half of the time screams only: “What are you doing? What the hell are you doing?” Because we had not gone so far in terms of preparing it. And the thing finally broke. And fortunately there was a telephone guide within it.

That's all real. Happened. And he never cut it. I just wanted to see what would happen. And sometimes I felt bad for the other actors, because, of course, they were not there all the time. And they didn't know what I was going to do. Pankow was afraid until death when he was driving: “You don't have business doing this. My life is in danger.” Shouting from the back seat.

That is a classic car persecution now. What made you want to make your own driving? That looks like a great decision but Also a little crazy.

First, you are young and you think you know what you are doing. And I had the idea that I could also be a type of acrobatics. Why can't I be a type of acrobatics? I didn't even think I was going to be a film actor. Then, suddenly, I was in the thing and I would get angry if I thought I couldn't use me in a shot. I remember that friend Joe Hooker, who was our acrobatics coordinator, and was talking about all these things he could and could not do. There were certain things that were not going to let me do it. But in general, I have to do a lot of what I wanted to do. What else am I going to do? Sit in a trailer? I was not used to that anyway, the entire movie of the movie where you hurry and wait.

Then, once Billy discovered that it was a game, he always wanted him to be part of him. Buddy Joe was really great. Dick Zike was the guy who did what he was driving. The acrobatics boys were fabulous. He didn't let me jump from the bridge. God bless you – Dar Robinson did that.

I am reluctant to spoil a 40 -year -old movie, but I have seen several times, and every time I am surprised that your character dies and happens so close to the end of the movie. Was it a shock for you when you first read the script?

I thought it was the best. I thought that was the key. At the end of the image, I remember that Billy came out and that we had a long afternoon talking. We were on the beach and he said: “They want to shoot another end.” I thought: “Billy, this is the reason we did this. All the reason I could interpret the guy in which I played it was because it does not come out of jail.” Otherwise, they are mistakes, they do the right thing. There was a moral, I felt. Chance, he pushed him too far. And I didn't seem correct to have them suddenly, it would only leave, “Are we not great agents of the Secret Service?”

That is what the movie did, I thought. Now granted, did it cost them at the box office? I guess. They certainly felt he would. It is shocking. I have a couple of 14 -year -old children who have not seen the movie. You will see it on Saturday. And there is a debate on whether to tell you what happens or not. And I haven't even concluded. I have half of my people telling me: “Hey, you have to tell them.” And the other half goes: “They do not destroy it.” Then, the debate continues, 40 years later, either the right thing. He triggered an alternative ending. We had to return to Los Angeles and shoot this nonsense where I was bandaged and we are supposed to be in Alaska somewhere, in a remote secret service station. We shoot in such a way that there would be no way to use it. It was simply ridiculous. But look, Billy had large balls, man. He did it.

And then “Manhunter” is such a different environment. It is very methodical and there is something really disconcerting about it. How was it changing a project directly to the next?

They were completely opposite things. Both symbolize a kind of gender of the slippery copy of the 80s, but it was such a different material. The characters were also completely different. You had my character in “To live and die in la”, I just wanted to jump from bridges, drive to the highway and shoot the bad. The “Manhunter” character, Graham, didn't want to have anything to do with anything like that. It was even reluctant to answer the phone. The character of “To Live and die in the” was more like me then, and the character of “Manhunter” is more like me now. Stay at home and forget about it.

“Living and dying in Los Angeles” was not disturbing. I was going home after a day and drank a couple of beers and saw a football game. While “Manhunter” was a much more difficult experience due to the material with which he is treating during the day. And it wasn't a method thing. It wasn't Daniel Day-Lewis.

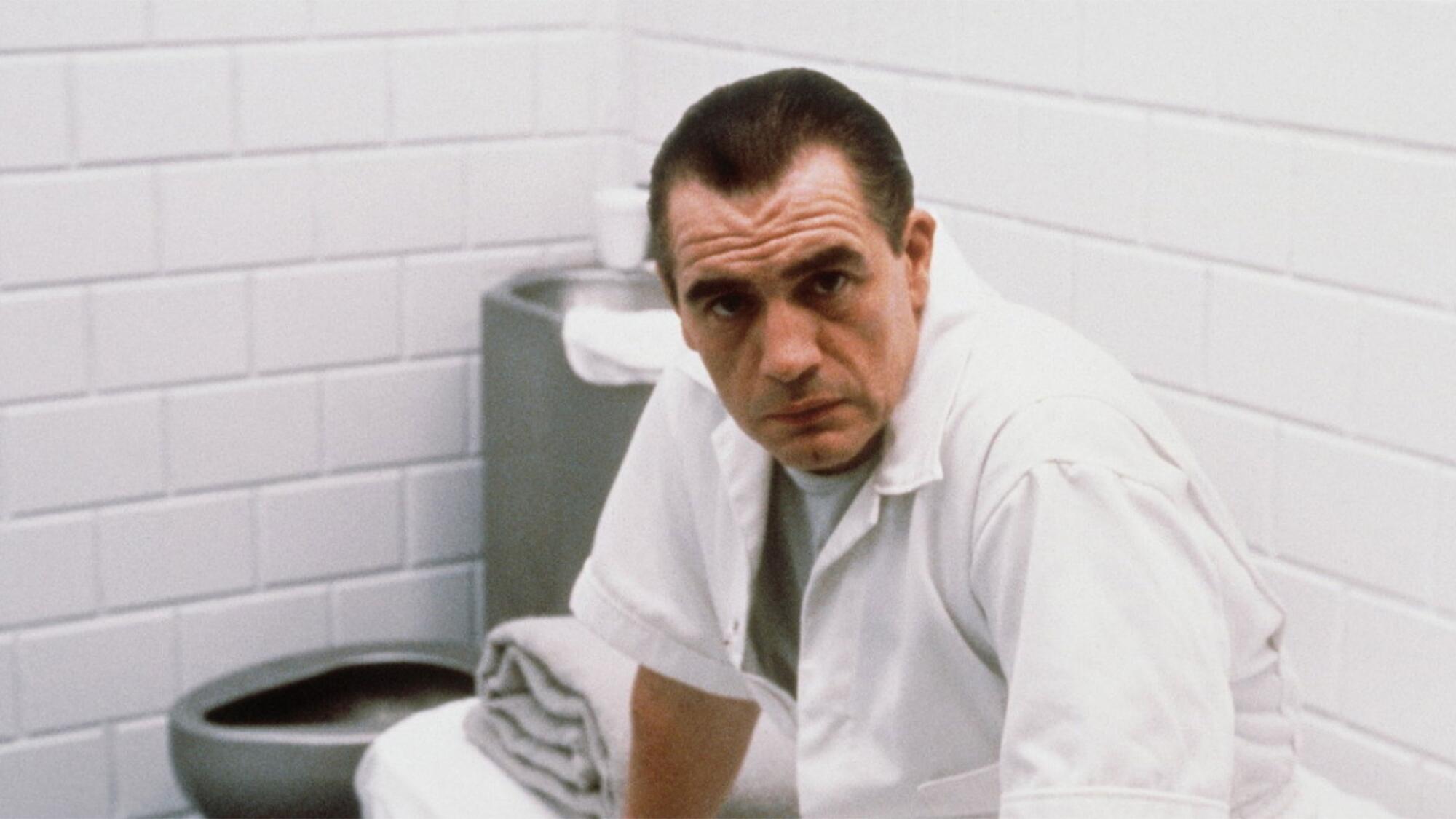

Brian Cox as Hannibal Leckor in the movie “Manhunter”.

(Rialto Pictures / Beyond Fest in American Cinematheque)

Serial murderers, profilers, that is such an accepted part of pop culture now. There are so many programs, movies and podcasts about thembut a he time was still new. YoIt wasn't something that everyone knew so much.

One of the things I liked about the “French connection” was the manufacture of heroin and falsification. When you see the falsification in “Live and die”, people were fascinated by that. And then we did “Manhunter”, and we went to the FBI laboratory and used things to lift latent impressions, all laboratory things. I found that people were fascinated by that. And that's why I knew that the idea of ”CSI” was the one that was, because people were fascinated with everything “How do you do this?”

I want to make sure to ask about his scene with Brian Cox, the Leckor scene. Really establish yourself and do A long dialogue scene, which must have wanted to make a Play in the middle of the movie.

Yes, it was. Brian, of course, is a wonderful theater actor. Interestingly we play a couple of the same parts in the theater in different countries. I worked with him basically only for about two or three days. He took a long time because, of course, Michael was doing all these very interesting camera things with the bars, going and coming. I loved him in a certain way and got it. And so it took a long time because there were many shots. I just remember that it was wonderful because I was really tampado. Brian was simply brilliant and surprising as a Leckor. He is my Leckor. Anthony Hopkins is fine, but it's something completely different for me.