“I am an earthling; Then I am galactic and then I am universal,” Alejandro Jodorowsky tells me in Spanish from his house in Paris during a recent video call.

At 95 years old, the Chilean-born cult director refuses to be tied to a physical place or a nationality, not even to this planet or his own body. The concept of the city seems irrelevant to him. And when I ask him what he thinks of Los Angeles before his next visit, he responds with his own cheeky question.

“Should I respond politely or should I respond in my own way?” she scoffs. After insisting that he let go, Jodorowsky continues: “I don't want to say, 'Los Angeles is so wonderful.' I can't tell you if I like it. It depends on the spiritual, intellectual, emotional, sexual, physical state I am in at that moment. I will respond when I get there.”

The iconoclastic Jodorowsky comes to town this weekend for a retrospective at the American Cinematheque; It is his first visit in more than six years. The series, which will air Friday through Sunday, includes sold-out screenings of his seminal psychedelic works “El Topo” (1970), “The Holy Mountain” (1973) and “Santa Sangre” (1989).

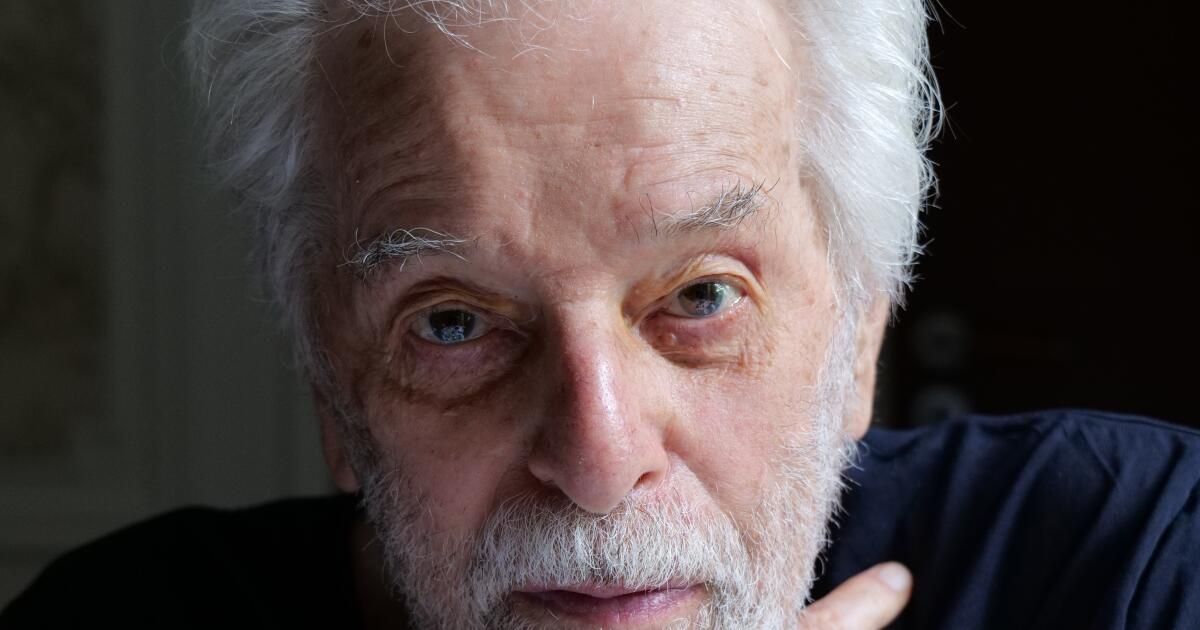

A scene from the movie “El Topo”.

(ABKCO Movies)

“We are thrilled to share his most iconic films at the historic Egyptian Theater so audiences can continue to discover and rediscover these surreal, mind-bending and singular works,” said Cindy Flores, film programmer at the American Cinematheque, via email.

Talking to Jodorowsky is a metaphysical experience. His brain-expanding comments about humanity's status in the cosmos often require some contemplation to digest. For example, take his lyrical reflections on why cinema continues to attract us.

“Cinema is an opening to creation,” he says. “We are tired of being locked in a physical body. We want to open ourselves because we see free bodies everywhere, in the seagulls flying or in a gram of dust carried by the wind.”

At his side during our talk is his wife of more than 20 years, an artist, Pascale Montandon-Jodorowsky, who occasionally jumps into the frame to confirm a name or numerical fact that may escape the filmmaker. Despite spending more than 70 years living outside his birthplace, Jodorowsky's Chilean accent is evident when he speaks.

His heady statements match what he has put on screen and in the pages of his comics for the last 60 years. As esoteric in their meaning as they are hypnotic in their imagery, Jodorowsky's films are modern fables. Entering them is like walking in a dream in which you have to accept a disconcerting logic.

In “El Topo,” his hypnotic 1970 Western, Jodorowsky himself plays a gunslinger traversing an arid landscape full of peculiar inhabitants. In “The Sacred Mountain” from 1973, heavily inspired by tarot cards, he is a sage, the alchemist, who guides others to immortality through ritual and sexually explicit tests.

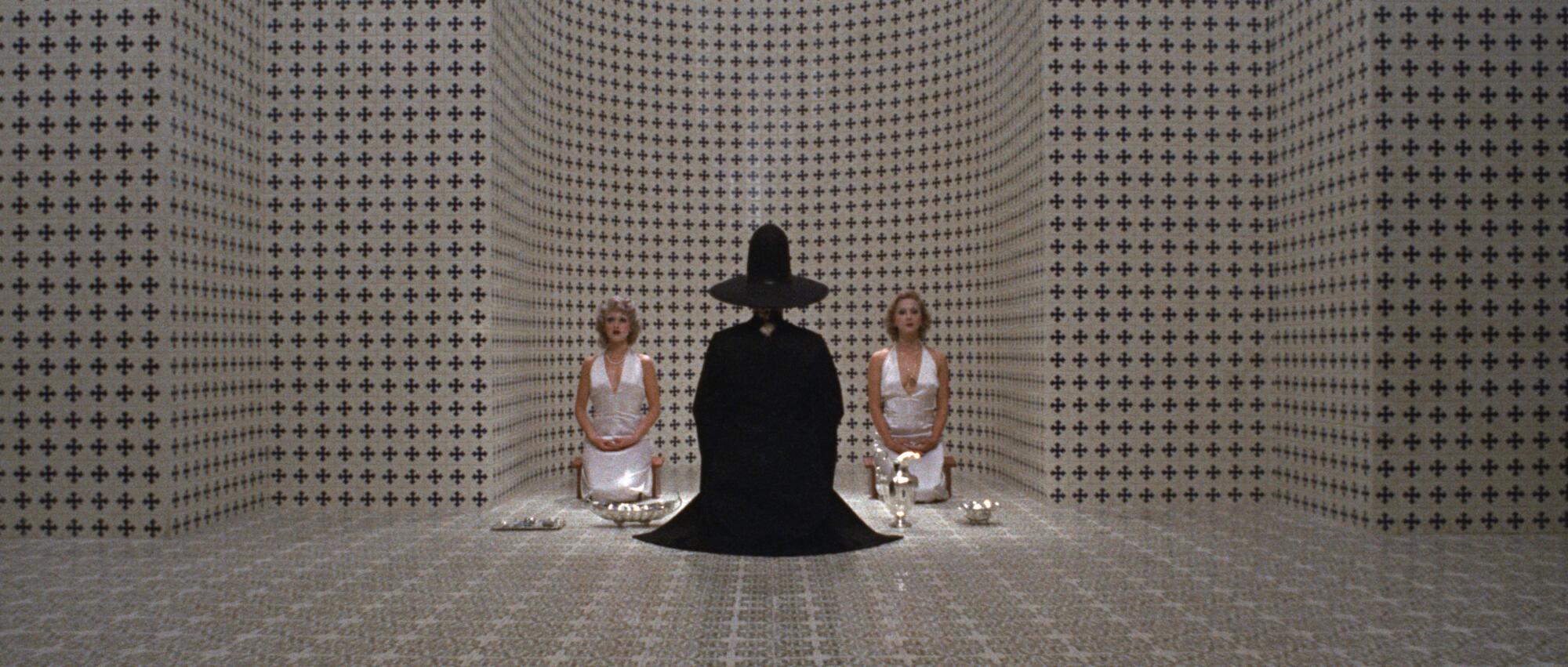

A scene from the movie “The Holy Mountain”.

(ABKCO Movies)

Hallucinogenic rocks from the original Midnight movie scene, Jodorowsky's work has long been an expression of countercultural transgression, the kind that could be called a trip. There is always a visual dialogue between carnal desire and enlightened thought.

Why do you think your films have endured over the decades?

“Because they are true,” says Jodorowsky, with absolute conviction. “They were not made by producers. They were made by people who love art. When they see them, people always say, 'These films are more modern than the ones currently being released.'”

Still artistically active, Jodorowsky has a full schedule in Los Angeles. In addition to hosting Q&As at his screenings, he will present an exhibition titled “Another World,” featuring paintings co-created with Montandon-Jodorowsky (under the joint moniker pascALEjandro) at the Blum Gallery.

And to top it all off, he will present the screening of his 2019 documentary “Psychomagia, a Healing Art”, accompanied by a master class on the therapeutic practice he devised using creativity as a vehicle to cure both emotional and physical ailments. Jodorowsky's book on the subject, “The Path of Imagination,” will hit stores later this year.

“It's a free healing that comes from my love for humanity,” Jodorowsky says of psychomagic. “A human being cannot achieve what he wants in this world or in others if he does not perform acts of love.”

Nothing excites Jodorowsky more than knowing that he will be received with packed houses, especially because he feels that today's youth has largely lost interest in cinema. However, they still want to see the visions of him.

“Before, everyone had to go to the movies,” he explains. “Now the young people don't go. They look for real depth, not fairy tales or war stories, but other things. Something that allows us to discover the inner mystery that we all carry inside.”

Jodorowsky's most recent fiction film projects, “The Dance of Reality” (2013) and “Endless Poetry” (2016), proved difficult to finance. Only thanks to crowdfunding and two angel investors who donated around 2 million dollars each was he able to complete them. Due to these financial constraints, the third part of a planned autobiographical trilogy addressing childhood, adolescence, and adulthood will be turned into a book.

“If it is so expensive to make films, I am going to make films without films,” he explains. “I'm going to do what cinema does in a different way, without images.”

Without mincing words, Jodorowsky declares that films are in a period of decline, especially those coming out of Hollywood, a system he calls a “prison” and to which he would never submit.

“I have made 10 films, which for a film director are few,” he says. “Another can make 100 movies because he makes fairy tales. It can be repeated. There is no great mystery to discover in those films. True art is not about totally entertaining the viewer but about changing their life.”

This brings us to the inevitable topic of Denis Villeneuve's two-part “Dune,” which has grossed $1.1 billion worldwide. Jodorowsky is used to receiving questions from the press about the sci-fi epic he attempted to adapt in the 1970s, with a fantastic cast that would have included Mick Jagger, Gloria Swanson, Orson Welles and his own son, Brontis. , like the messianic hero Paul Atreides. (Frank Pavich's 2013 documentary “Jodorowsky's Dune” chronicles the director's fascinating, if failed, attempt.

Not even the premiere of Villeneuve's second part convinced the maestro to see them. Your reasoning for it? Civility mixed with hard-earned arrogance. “If I'm going to see the movie I'll have to be polite and praise it a little,” he confesses. “But I am sure that they will never be able to have Salvador Dali as Emperor.”

Jodorowsky is pleased to find that his radical ideas continue to gain followers: “The Incal,” a comic he published during the 1980s centered on a triangular artifact containing the world's wisdom, is being adapted by the “Jojo Rabbit” filmmaker. Taika Waititi. Jodorowsky keeps expectations of him in check.

“He will only be able to express an approximation of what he wants, because where there is a producer in charge there is no perfection,” warned Jodorowsky, always cynical about the money side.

He cares little for materialistic notions of success. “Look at me, I'm 95 years old and I'm here saying so many stupid things,” she says with an infectious smile. “I'm having fun. And if I can have fun, I made it. I'm not suffering. I'm happy to be creating in every way possible.”

At his age, Jodorowsky's thoughts often turn to what awaits him next, not professionally, but when he transitions from this plane of existence and ascends to something greater.

“I am condemned to spend less time on Earth,” he tells me matter-of-factly. “I have fewer years left than you. Because you have a black beard and I have a white beard. White indicates less life time. I have to accept it, but I'm not on the decline yet.”

Even when his mortal body no longer shares this space with us, he plans to refuse to disappear.

“I will not be an immobile skeleton,” he says. “I am going to be something else because I believe that there is eternal life. You and I are going to talk in a different way. We will talk for thousands of years. That is my hope.”

How can I not believe him? As soon as Jodorowsky says goodbye, hugging his wife tightly, I already look forward to our next meeting somewhere in the endless unknown.