In the sense that television is a lens through which we see ourselves, it is more often than not a lens that is cracked or greased with Vaseline to make things crazier or prettier. A certain kind of restraint and support (given the relative lack of commercial potential) is needed for television to address life as it is, without the mediation of scriptwriters or reality show producers. For that, public broadcasting will have to be used.

Filmed in five installments over 34 years, “Two American Families: 1991-2014,” which premieres Tuesday on “Frontline” on PBS (and is also available to stream on the PBS app and PBS.org), looks at a pair of Milwaukee families — the Neumanns, who are white, and the Stanleys, who are Black — after their breadwinners lose their unionized manufacturing jobs.

Although originally planned as a single documentary (the original installment was titled “Minimum Wages: The New Economy”), over time it becomes a story of what has not changed and how that reality has changed the lives of its protagonists.

Directed by Tom Casciato and Kathleen Hughes, with Bill Moyers as narrator and interviewer, it bears a resemblance to Michael Apted’s poignant British “Up” films, which began in 1964 with “Seven Up!,” focusing on a variety of 7-year-olds, and, returning every seven years, ended in 2019 with “63 Up!.”

That series, which began as an investigation into the effects of social class on children's outlook, evolved into a more general look at the ups and downs of individual lives. Social and emotional stories are inseparable, both here and there.

The working class has been underrepresented on television, especially those living near or below the poverty line, where bills go unpaid and luxuries are out of the question. There was “Roseanne,” before the show went off the rails, “The Middle,” “Good Times,” “The Honeymooners” and certain characters on “Friday Night Lights.” Food insecurity is dramatic, apparently, only if it’s part of a post-apocalyptic scenario; we’d much rather see rich people fighting over extraneous money than a family fighting to stay in their home, unless that home is a castle.

Though “Two American Families” is never expressly political (it’s not known how any of these people voted, or if they did), it is implicitly a critique of a system that keeps the poor poor and makes the rich richer while hollowing out the middle class. The villains looming here include exorbitant interest rates, predatory banks, contract labor, a health care system that punishes those without benefits (and anyone else without a job), and the destruction of the labor movement (which is now, at least, experiencing something of a renaissance). We see presidents from Bill Clinton onward promising a brighter tomorrow, even as the Neumanns and Stanleys barely change or change for the worse.

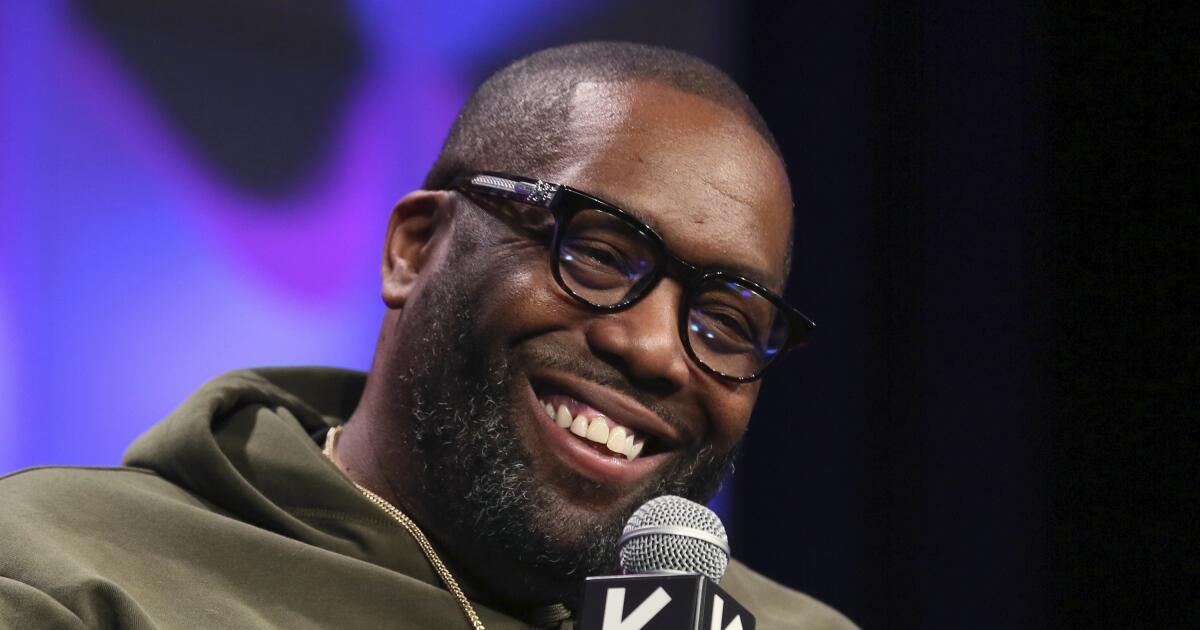

“Two American Families: 1991-2024” follows a pair of families living in Milwaukee.

(Frontline / PBS)

“People are getting angry, they are getting frustrated, they are getting violent because they don’t see any way out,” says Terry Neumann. “There are so many people who are struggling in the same way with the cost of everything and not enough pay to cover monthly expenses. It’s like we haven’t made much progress.”

Though the Stanleys face the added burden of racial discrimination (Jackie, who has a real estate license, can't sell houses in wealthier white neighborhoods), the families aren't all that different. Both are churchgoers and have a slew of kids. Each has to contend with increasingly violent neighborhoods. Jobs come and go, the parents hunch over classified ads as they search for work that pays a fraction of a living wage. They live paycheck to paycheck, paying bills and running up credit card debt. “It's called robbing Peter to pay Paul,” Jackie says, “and I steal so much from Peter that Peter just stands there.”

Obviously, this is merely a sample of lives lived every day of every year over three decades, not just during the filmmakers’ visits: 34 years in two hours, edited to tell one story. The stop-motion effect highlights both stagnation and decay. Neighborhoods deteriorate, health problems arise. (“I planned to get older,” Jackie says, “but I didn’t plan to get sick.”) People just get older.

Yet even as they struggle, our characters survive. Claude and Jackie Stanley, holding hands as they give interviews, are the picture of a solid marriage; the Neumanns, who work different schedules and are rarely seen together, drift apart over the years, but both sets of parents remain committed to their now-grown children, some with children of their own, with their own hopes and challenges. Not all remain in Milwaukee.

Above all, the series is a rebuke to the fantasy, so deeply held by certain (rich) politicians, that any family can (and some of them claim to) survive on a single salary. Your own resources can only take you so far.

“I think we’re kidding ourselves if we think it’s just a matter of hard work,” says Keith Stanley, whose parents fought to put him through college and who now runs an economic development agency in Charlotte, North Carolina. “A lot of times, it’s a matter of luck, who you know, your ZIP code, and I think that sometimes gets confused in our society with, ‘Work really hard and you’ll succeed. ’ I think there’s a lot more to that equation.”