Just as the country prepares for what promises to be one of the ugliest and most historically significant presidential election cycles, Max gives us “The Girls on the Bus.” Inspired by Amy Chozick's 2018 book, “Chasing Hillary: Ten Years, Two Presidential Campaigns, and an Unbroken Glass Ceiling,” she follows four women as they cover a fictional primary for a wide variety of media outlets. (Warning: there is an influencer involved.)

As the title indicates, it aims to be a kind of feminist version of Timothy Crouse's classic 1973 portrait of campaign journalists, “The Boys on the Bus,” with excerpts from Hunter S. Thompson's “Fear and Loathing: On.” “Campaign Trail '72” is included. (In fact, Thompson, who died in 2005, is a real and rather irritating character here.)

Instead, what emerges is a manic Grrrl Power pixie dream drama in which all the women run around in a cloud of charger cords, vibrators, Twizzlers, and barely packed suitcases, seemingly too overwhelmed by evasive press secretaries, fellow conspirators and their own backstories. to present something resembling the regular coverage that this job requires.

Also, the two who work for the newspapers are more concerned with front page placement than digital issues, which is just adorable. All of this would be fine if it weren't for the underlying, and clearly unintentional, message that female journalists are more interested in exploiting their own psyches than in doing their jobs.

Though peppered with references to all sorts of important topics (double standards, authenticity versus impartiality, cancel culture), the series focuses on the emotional relationships of reporters. With as many iterations of these as one can imagine, along with an emerging mystery about the money trail and the campaign's obligatory connections, “The Girls on the Bus” feels more like the love child of “Scandal” and “The Sex Lives of College Girls” than any of the books mentioned above, including Chozick’s.

It's certainly tonally intentional, but it's still a little strange considering how many details, including references to some of his actual set pieces and snippets of dialogue, are lifted directly from “Chasing Hillary.” Chozick, along with Julie Plec (“The Vampire Diaries”), created and wrote the series, which jumped from Netflix to the CW before landing on Max, and a distinct CW flavor remains (Greg Berlanti is one of the producers).

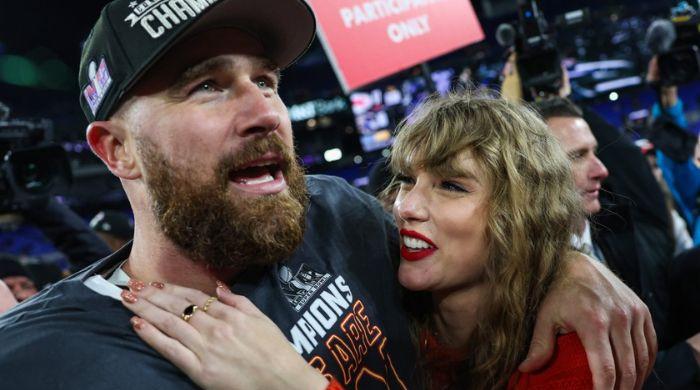

Melissa Benoist plays Sadie McCarthy, a reporter for the New York Sentinel, in “The Girls on the Bus.”

(Nicole Rivelli / Max)

“Supergirl”'s Melissa Benoist plays the lead (and Chozick as a stand-in), one Sadie McCarthy. A New York Sentinel reporter whose “conversations” with Thompson warn about the show's tense but frothy tone, Sadie's reputation suffered during the previous presidential campaign, after the candidate she had been covering lost. Sadie's tears went viral as a symbol of journalistic bias.

When her editor, played by Griffin Dunne, assigns her to cover the elderly candidate in this race, Sadie puts her foot down and convinces him that she has learned her lesson and can be trusted to report impartially on the frontrunner.

I don't know how things work at the Sentinel, but it seems to be a pretty haphazard, last-minute way of planning political coverage. But then Dunne's character, with a signature scarf, lots of cigarettes and endless encouragement of tough love, seems based on “Chasing Hillary's” depiction of the late, lamented New York Times columnist David Carr more than any editor. real politician that ever existed.

And I honestly don't know how to categorize any series in which a journalist talks about memes while smoking indoors. Was there some space-time continuum glitch that I missed?

In any case, the decision allows Sadie to quickly reunite with Grace (the always magnificent Carla Gugino), an older, wiser (aka more talkative) journalistic icon from a competing newspaper (presumably the Washington Post) who is known for apparently getting, even during the election campaign. Together, they roll their eyes at the entrances of Kimberlyn (Christina Elmore), a reporter for a conservative cable station, and Lola (Natasha Behnam, who steals every scene she's in), an influencer who courts sponsors and who openly supports Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. -as a candidate.

Of course, the four, all women who question on one level or another the ability to remain truly impartial about anything and the toll such a demanding profession exacts on their backstories, that is, their lives, will soon become best friends.

Natasha Benham plays Lola, an influencer who reports on the election campaign in a less conventional way.

(Nicole Rivelli / Max)

Relationships, not information, are the driving force of “The Girls on the Bus,” which is surprising because Chozick knows better than anyone how long and hard women have had to fight to be taken seriously as journalists (in “The Boys on the Bus,” Crouse describes the few women who cover the campaign as “pretty” or “plain”).

Obviously, a show in which the main character talks to a long-dead journalist doesn't have the same tone or audience as, say, “The Wire.” But it would have been nice if “The Girls on the Bus” had portrayed the chosen medium in a less soap opera-like way, especially if at least part of the goal was to chronicle the real demands of campaign journalists and/or restore trust in the press. during an election year.

Instead, each episode of “Girls on the Bus” is a campaign that reports the story of Izzy-kills-Denny-to-get-him-a-new-heart-and-then-sees-his-ghost-of- “Grey's Anatomy”. ”was for the medical profession. That can appeal to a certain type of audience, and I admire anyone who tries to make a television show about journalists because it's a great visual and narrative challenge.

With television presenters, in the style of “The Newsroom” and “The Morning Show,” there is at least a little glamor and bustle of a television studio. But the business of actual reporting? Let's just say that the most accurate cinematic image of a reporter's job remains the scene in “All the President's Men” when Woodward and Bernstein examine every request the White House made to the Library of Congress for an entire year. And even that scene depends on a magnificent upper setback, which accentuates the symbolic rings within the rings of the building's historic reading room, to make it interesting.

No matter how explosive the story being pursued may be, the actual work of news gathering and production is visually repetitive and often silent. “The Boys on the Bus” illuminated many of the personalities (almost all male) involved in the coverage of the 1972 Democratic primaries and the subsequent contest between George McGovern and then-President Richard Nixon, but served primarily as a highly analytical critique. to pack journalism. , in which a tangle of reporters must report daily on the same series of often not very significant events. Not only did Crouse believe that herd mentality resulted in a “losing the forest for the trees” situation, but he also suggests that a largely liberal press felt compelled to be tougher on McGovern than on Nixon.

In her book, Chozick also questions the ability to remain impartial and insightful while being part of a pack, as she does most obviously in “The Girls on the Bus.” But when Chozick was one of those “girls,” she also managed to file stories daily, often more than one.

The other challenge a show about journalists faces is, as I'm demonstrating now, that it will first be critiqued by real journalists. As Aaron Sorkin discovered in “The Newsroom,” critics and columnists, who happily praise dramas in which doctors, lawyers, educators and even mobsters behave in ways no real member of their profession would ever do, tend to jump happily about anything real or real. They perceive inaccuracy in the way a reporter does his or her job and tear the program to pieces.

So I tried, as hard as I could, to see “The Girls on the Bus” for what it is: a television show designed to entertain, rather than a docudrama created to inform. And there are plenty of entertaining moments, some thought-provoking subplots, and an excellent evocation of how exhausting it is to be shuttled from state to state to cover candidates who monotonously refuse to give interviews.

If only it didn't make everyone involved in maintaining a free and informed democracy look so foolish. In a year when the presumptive Republican nominee is up to his eyes in legal trouble and doubling down on his previous attempt to overturn a legal and fair election, when he and his supporters have helped diminish the country's trust in the press and multiple platforms news organizations have experienced catastrophic layoffs, tense and frothy might not have been the way to go.