It was a cold, wet afternoon as I walked down desolate Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. A countercultural thoroughfare in the late 1960s, the street retained almost none of its colorful flower power. But suddenly I smelled incense and heard a recording of Messiaen's psychedelic “Turangalila-Symphonie.” Annapurna, the flagship store that opened in 1969 at the same time as the historic protests at the now boarded-up People's Park, has survived.

The combination of this specific smell and the music, so familiar from my student days here, acted as a kind of nostalgic drug. For a surprising moment, I was transported back in time. But what's even more mysterious is that it was the music, the scent, and the color that recently brought me to the Bay Area.

The San Francisco Symphony was experimenting with scents in the concert hall for Scriabin's “Prometheus, The Poem of Fire,” a 20-minute symphony featuring solo piano. The Russian mystic composer experienced synesthesia, the neurological condition in which the brain involuntarily associates one sense with another. Scriabin's brain (like, coincidentally, Messiaen's) attributed specific colors to specific harmonies.

In “Prometheus,” Scriabin even went so far as to include a part for the “color organ,” a newly invented instrument that projected colored lights, in his 1910 score. But instead of one color mixing with another to achieve a dramatic effect, the result was a cloudy gray. Technology has evolved, and Jean-Yves Thibaudet, soloist with the San Francisco Symphony, had long dreamed of adding more senses to Scriabin's mix. Why not smell? The orchestra's musical director, Esa-Pekka Salonen, was intrigued.

I had doubts. The odors persist. As a kid enamored of movie tricks, I convinced my parents to take me to the 1960 Smell-O-Vision “Scent of Mystery,” which had dozens of everyday smells coming from under the seat. In the end, there was a stench of all-purpose in the theater. That was disgusting.

Mathilde Laurent, perfumer at Cartier in Paris, created three original fragrances for “Prometheus.” Capsules of dry concentrate projected from diffusers beneath every third seat. Large wooden devices around the hallway cooled and dried the air, so odors did not linger. That worked.

A crown of neon tubes high up and along the walls of Davies Symphony Hall looked kitschy but approximated Scriabin's color concept. That worked too.

“Prometheus” is an extraordinary score; Scriabin's extravagance goes far beyond synesthesia. Written for a large orchestra and inspired by Madame Helena Blavatsky's Theosophical Society, the symphonic poem is a fantastical transformation of the Greek myth of Prometheus, who steals fire from the gods. Scriabin's rich blend of erotic and spiritual ecstasy follows the mystical process of humanity (the piano), in the form of an all-encompassing ego (the brass affirms in an endless chorus an “I am” theme) arising from an incipient and imperceptibly silent chaos merging into a deafening and delirious joy, joined by an otherworldly chorus.

The lighting effects are intended to be full of symbolic intent. There are themes of creative principle and will and things like that. Blue, for example, is surpassed by the yellow of the sun, and that is supposed to mean something. But no one is going to understand that.

The flavorings were supposedly added for a different purpose. The highly publicized event caught the attention of the British weekly magazine New Scientist, which points out in its latest issue that smell ignores reason. Smell stimulates the parts of the brain linked to memories and emotions, just as Annapurna incense had done for me. Presumably, then, the art of smell can prepare our minds for new experiences.

In a pre-concert talk for the Sunday matinee, which I attended, Laurent described his first scent as evoking a feeling of anxiety at the beginning, where the music represents the world before civilization. It was a bit mushroomy. He selected a perfume that he had already invented for Cartier, sweet and sexy, to accompany the fire and passion. The last one was covered in joy grass.

Maybe it was just me, but the smells landed in the wrong part of my brain, knocking on the door of reason. Scriabin leaves you with enough questions, and here are more. Salonen and Thibaudet's sensational interpretation of “Prometheus” (transparent, nuanced and colorful) did not need to tickle the senses any further.

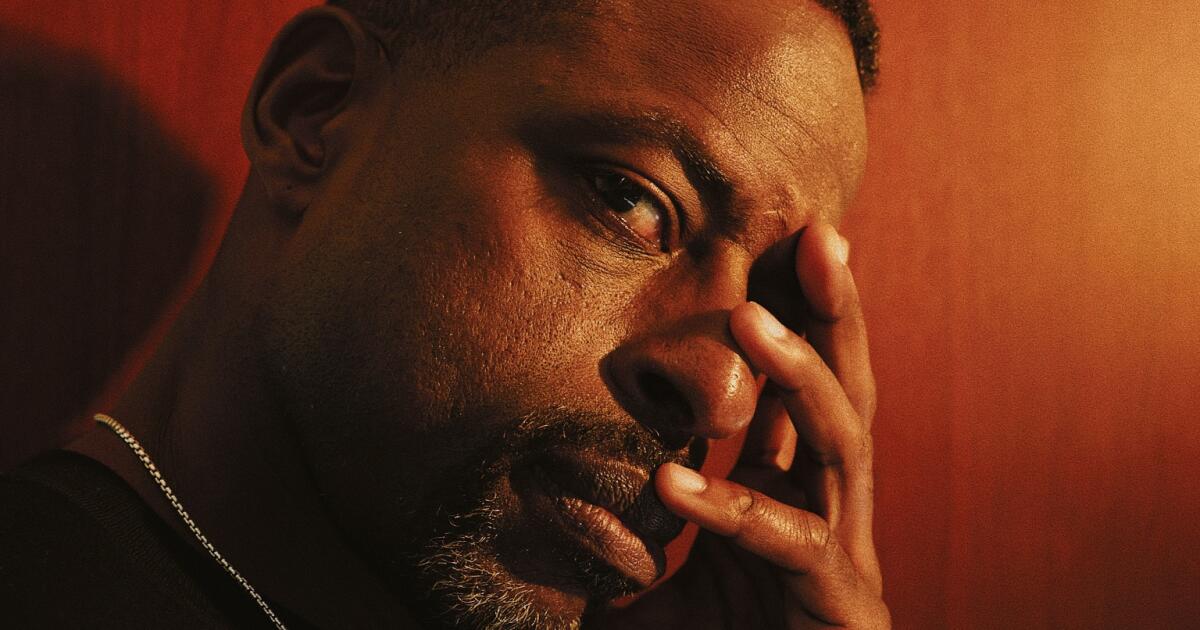

Michelle DeYoung and Gerald Finley sing while Esa-Pekka Salonen conducts Bartók's “The Castle of Duke Bluebeard.”

(Brandon Patoc / San Francisco Symphony)

A new revelation came after the intermission with an even more impressive concert of Bartók's “The Castle of Duke Bluebeard” that demonstrated the radical difference between theater and synesthesia. This time the neon lights underlined the atmosphere: red for the blood dripping in the castle's creepy rooms, green for the grass. They neither bothered nor increased, they were simply obvious.

But in one of the most magnificent orchestral climaxes in symphonic literature, when Bluebeard opens a door revealing a vast landscape, Salonen turned to the audience as he conducted, and the hall burst into brilliant daylight. Dazzling lighting and an overwhelming orchestral effect, not the color, made this take my breath away.

Otherwise, this “Bluebeard” needed no theater, thanks to Salonen's unerring sense of drama, along with ideal soloists: a fascinating Breezy Leigh (the narrator), an introspective Gerald Finley (Bluebeard) and the radiant Michelle DeYoung ( Judith).

I was in Berkeley on Saturday for one of the Kronos Quartet's “Five Decades” shows, celebrating the groundbreaking group's 50th anniversary. The Zellerbach Hall program included Sofia Gubaidulina's Quartet No. 4, one of more than 1,000 Kronos commissions.

As it happens, Gubaidulina is another Russian synesthete with a strong spiritual bent, and she included colored lighting effects in her score. Among his multitude of innovations, Kronos pioneered his chamber music concerts with lighting design shortly before Gubaidulina's 1992 premiere at Carnegie Hall.

That had been advertised as a big deal in New York. The work uses tape-recorded string quartet sounds alongside live performance. Gubaidulina wanted one type of lighting for what she called “unreal” sounds of balls bouncing off the tape strings and another for “real” live sounds. I remember the music from that premiere, but I don't remember the lighting being a big deal.

In Zellerbach, Gubaidulina's quartet performed as part of a tremendously varied program that highlighted the world premiere of “Segara Gunung” by Javanese composer Peni Candra Rini, in which she performed as a dazzling vocalist. To achieve a striking visual effect, he included shadow puppet theater.

I caught up with Kronos first violinist David Harrington at “Prometheus” on Sunday and asked him about the decision to omit Gubaidulina's desired lighting. He said Kronos never used Gubaidulina lighting even for the Carnegie premiere. He felt it was too strident for this exquisite score.

Live performance is theater. Lighting, movement, design, staging, acoustic projection all have their place, and perhaps smells too. But you need a director who can translate a synesthetic vision to the stage.

Salonen, in fact, had just that at a “psychedelic night” at the Hollywood Bowl a quarter-century ago, when he was music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. For this reason, Peter Sellars related “Prometheus” to the ritual of Native Americans. The aromas were of what the party next door had brought for a picnic dinner, or a sneaky whiff of marijuana.