In “Inside the Episode,” the writers and directors reflect on the making of their Emmy-winning episodes.

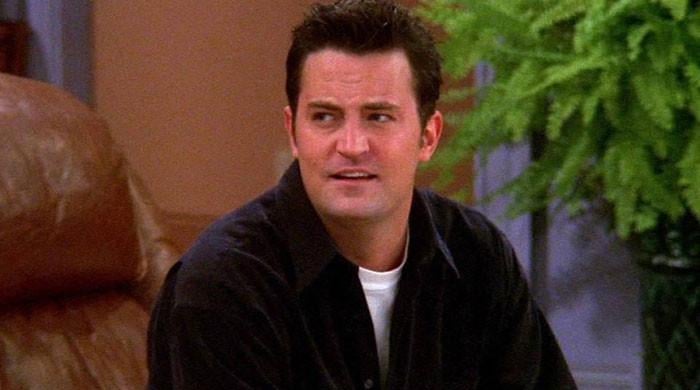

A CPR dummy becomes one of Buffalo Bill's victims in “The Silence of the Lambs.” A cat falls through the ceiling. The best boss in the world (in his opinion), Michael Scott, is roasted. These are just some of the antics that make up “Stress Relief,” a two-part episode that aired in 2009 during the fifth season of NBC's mockumentary “The Office.”

Jeffrey Blitz would win a Comedy Director Emmy that year for overseeing all of this mayhem. Blitz, who broke into the business with his 2002 Oscar-nominated documentary “Spellbound,” talks to The Times about the rules of directing a scripted comedy that feels like a serious documentary, the art of cat stunts and the commitment of comedian Cloris Leachman with her craft. .

I'm not sure there is an easy way to answer this, but what are some of the main differences between directing A real documentary and directing a comedy that looks like a documentary?

Appearance is really the only similarity, and that's a trick, of course. Real life doesn't stick to a script, doesn't have more than one take, and can have quite dubious craftsmanship. “The Office,” as a mockumentary, borrows the style of a documentary, but is otherwise scripted like any scripted show, with one exception: the amount of improvisation. Even there, it feels less like real life and more like a game.

What are some things to remember about making a mockumentary look like a documentary? How are the original settings maintained? Were there rules on “The Office” about how much originality you could use in interview segments where characters explained things directly to the camera?

There were rules for our filming. Or rather, there were standard procedures that usually originated with showrunner Greg Daniels. As the directors came to watch the episodes, they learned these basic ideas. We were always free to challenge those rules, but we never did it simply to be “new”: it always had to be a choice based on character and story. However, in a broader sense, a camera would almost never go where a camera operator in a documentary, or a camera stand, could not exist. We tried to stay true to that, not out of duty, but because it helped create the feeling of real human beings watching/recording/present at all times.

Were there rules in place about how often cameramen “filming the documentary“ Could or would you get involved? This episode begins with Dwight (Rainn Wilson) starting a fire to test his co–workers emergency preparation training. The supposed cameramen who make this documentary do not prevent him from doing so. But they do warn Pam (Jenna Fischer) that there is a fire.

The basic approach was that the camera crew should never be involved, as in a traditional type of documentary. But, as in the real world, when the human stakes rise to a level where film ethics are less of a concern because real life is at stake, things get trickier. I imagine that if I were part of the documentary team and a thug like Dwight started a fire, I would feel that the scene was worth exploring unintrusively and there were plenty of ways to handle it before it got out of control. On the other hand, if I felt like the staff (and documentary crew) were truly at risk, I'd feel comfortable taking off my documentary hat and putting on a more human one.

Dwight soon learns that his co–Workers do not remain calm under pressure. ailurophil Angela (Angela Kinsey) rescues a cat that has been hiding in the office and throws it into the Oscar (Óscar Núñez), who tries to escape through the roof. He misses and the cat crashes into another part of that ceiling. What was the cat casting process like? How did you decide on that cat? How many takes did you have to get the cat joke and the Oscar joke?

In the original script, Angela threw the cat onto the ceiling and Oscar simply kicked it down. I thought it was too petty for Oscar. Walking around the set, looking for a fun alternative, I cast so that it would pass through Oscar's hands, disappear into the open part of the false ceiling, and fall unexpectedly through another ceiling slab.

We quickly ruled out a stuffed cat (even the realistic ones looked fake) and instead came up with a very elaborate approach that involved using two cats that looked identical. One would be the one that Angela's double would throw into the arms of a cat sitter hiding on the roof behind Oscar. That cowboy would catch the cat for sure. About six feet behind them, another cat was hidden on the ceiling with a matching cat placed on an already scratched ceiling tile so that the matching cat could be dropped more safely.

But the best laid plans of cats and men. …On the day of filming, Angela's double threw Cat 1 onto the roof, but the catcher missed, although he didn't see it from the dropper behind her. What does it mean two In reality, identical cats crossed the roof, one as planned, the other quite scared but fine after taking the trip of his life. We were filming with two cameras and luckily one of the cameras missed the second fall of the cat, so we were able to use that angle to maintain the gag. After that, there were no more shots with the cat. By the way, I thanked the cat when I won the Emmy for that episode..

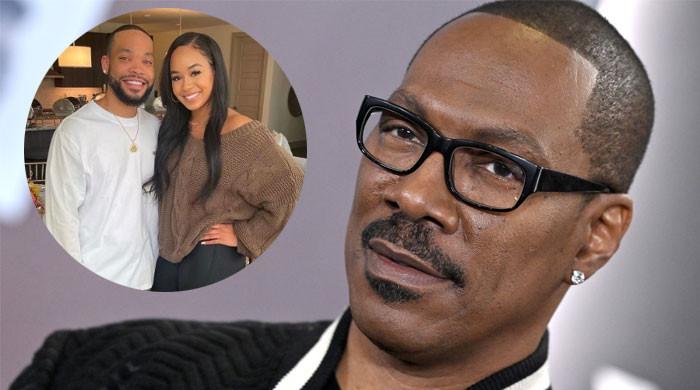

Jeffrey Blitz won an Emmy as comedy director in 2009 for the “Stress Relief” episode of “The Office.”

(Staff illustration; Matt Sayles/Associated Press)

Were there conversations about how elaborate you could get there without losing credibility?

By season five, the tone of the show, the world it lived in, was pretty clear to everyone who worked on it. I will say that I think everyone knew we were going to do something big for that cold open and some of the more normal episode backups were cut. For example: When Kelly Cantley, one of the assistant directors on “The Office,” initially broke down the schedule, all the segments of that cold open were supposed to fit into half a day. I told Kelly I wanted to go big here and dedicate a full day just to the cold open pieces (a very rare time allocation on “The Office”), but she understood and rearranged the schedule to give me the full day to those pieces.

Dwight's fire–the alert test fails and Stanley (Leslie David Baker) suffers a heart attack, causing the staff to attend CPR training. Dwight mocks this and butchers the CPR dummy so he can use its face as a mask as if he were the serial killer from “The Silence of the Lambs.” How many CPR dummies had to die because of that face? What were the conversations like with the props department about what that would look like? What was it really made of? Because I always think he looks like Silly Putty.

The CPR dummies were the work of “The Office” prop master extraordinaire, the late Phil Shea, who experimented with the actual material of a CPR dummy and discovered that it could work well. Rainn nailed the action right from the start, so there weren't as many horribly ruined dolls as there could have been. The actor who played the CPR instructor was a real CPR instructor who, as I remember him, was completely ecstatic about his luck in getting the role. She charmingly went on to say how special this all was, giving voice to what I and many of us felt working on that show.

This episode is also unique because there is a movie within the program. Pamela, Jim (John Krasinski) and Andy (Ed Helms) illegally download and watch a fake indie where a character played by Twenty-one breaks up with his girlfriend, played by Jessica Albabeing with his grandmother, played by Cloris Leachman. How did that casting come about?

As I recall, and this should all be questioned by those who care because, you know, it was 2008 when we had a lot of fun, Jack had already signed on while the script was still being written. The role of Cloris Leachman was initially envisioned for Angela Lansbury, who was not available. And Jessica signed after Jack and Cloris were doing it. There were several different versions of what the film would be, including what genre, before this sort of “Graduate” type independent film came into focus.

One story I love from the filming of this is the clip where Jack pulls Cloris out of the bathtub. Cloris, who was a committed actor through and through, wanted to perform the scene naked, without the usual flesh-colored swimsuit, to really sell the passion. He had to lower it to keep an orderly group that moved quickly. But I will always treasure the conversation between Cloris, Jack and me.

Sometime, Michael Scott by Steve Carell, the head of this operation, decides he needs to get the team together for a Friars Club-style roast of him. This backfires and the jokes become quite cruel. I don't know if any of the roasts were improvised, but did Carell know in advance what he was going to say? How did you work to get reactions not just from him but from everyone else in the room? Were there jokes that were changed because they were too bad?

All roasts were written, at least in their basic form. But look, we're talking about Steve Carell. Man's talent for taking root, for making himself real, present and alive, in situations that might otherwise seem patently absurd, is unsurpassed. Many jokes were cut, but it was more a matter of time than because the tone was too exaggerated.

I'm sure we modulated on set and editorial decisions were made to upstage him, but everyone knew the goal. It was Steve's idea to take a sort of Nixonian stance upon realizing that he is the target of ill will. I always loved that choice; Even then, even childish and wounded, Michael Scott is, indeed, great.

The catalyst for the episode is Stanley's heart attack, and it ends with a huge, guttural laugh as Michael roasts him. This makes it seem like all is forgiven. How important was it to end the episode with Stanley laughing? How did you work with Baker to get such a throaty response?

Leslie's laugh is genuinely Leslie through and through. There was no enthusiastic directorial work on my part, except that I knew to step back and let him be him.