The stories of hardship, dedication and love of music in the Oscar-nominated short documentary “The Last Repair Shop,” about the unseen heroes who repair musical instruments for students in the Los Angeles Unified School District, tend to leave no one indifferent. no spectator, and even less. the film's co-directors, Ben Proudfoot and Kris Bowers. (The film is co-distributed by Searchlight and LA Times Studios.)

“I still cry involuntarily and we've been watching this movie for four years,” says LAUSD alumnus Bowers, a sought-after film and television composer when not collaborating with Proudfoot. (They also made “A Concert is a Conversation,” nominated for an Oscar in 2021.) Bowers cites the story of Paty, a brass instrument technician who, before being hired at the shop, struggled to survive, as especially poignant as he became a father. himself since he started working on the film. “His vulnerability and openness about what it was like to be a single mother without the resources to support his family breaks me.”

Also count Los Angeles' own leaders among those affected. Proudfoot says: “We were in City Hall and these tough councilors were saying, 'I blew the trumpet!' He calls the film “this special key that unlocks everyone's childhood.”

“The Last Repair Shop” directors Kris Bowers, left, and Ben Proudfoot.

(Breakwater Studios)

What went through your mind when you learned about this hidden gem of a city-funded service, operating for six decades?

Kris Bowers: When you're a kid you don't think about that, do you? When an instrument doesn't work, you send it away, it goes somewhere, then it comes back and you're excited to have it. I remember spending a lot of time at the piano, expressing myself, playing songs and not thinking about how that was facilitated.

Ben Pie Proud: Esteban [Bagmanyan]who is the host and hero of the film, tuned the piano at Kris's elementary and middle school 20 years earlier.

Arches: Discovering: “Wow, has this place been a part of my musical journey?” It was exciting to meet these people and how their craft is something that means a lot to them too.

Did the workshop employees participate enthusiastically?

Proud Foot: The four people you see in the film are literally the only ones who raised their hands to be interviewed. And it was one epic story after another. Then Kris came in and said, “We have to interview the kids.” And she changed the movie.

Arches: I think what was so humiliating about these artisans is that they are doing this without even knowing the children; They never get the satisfaction of seeing relief on the child's face. For me, it was this really interesting distance between two people who have this secret communication. That seemed important to me.

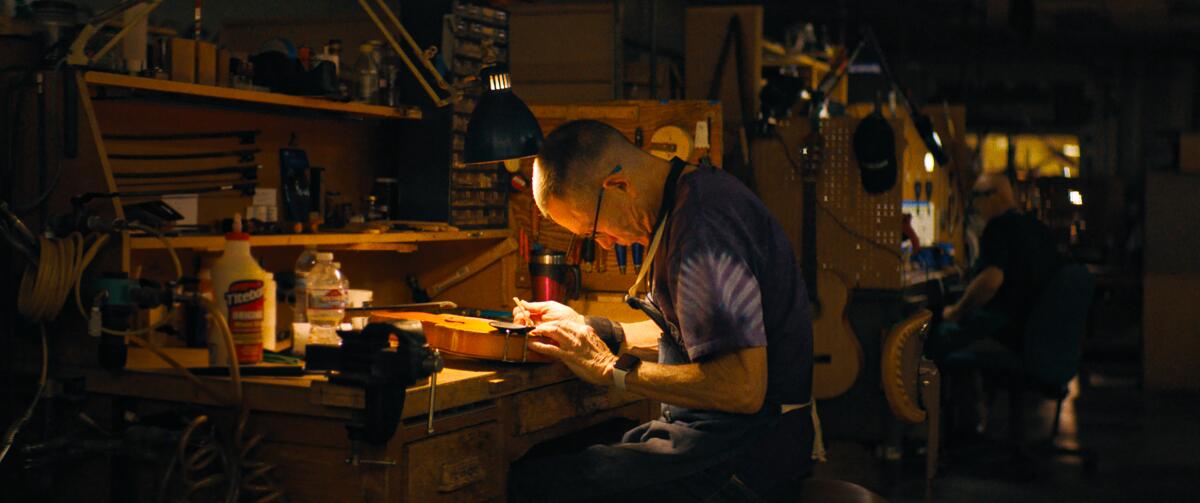

Dana Atkinson works repairing a string instrument in a scene from “The Last Repair Shop.”

(Breakwater Studios)

The close-up photography of the repair work is very lush. It makes the instruments look so beautiful and complex.

Proud Foot: What guided the look of the film was the very real practice of sticking a light bulb into a saxophone, or anything with valves, to see if there is a leak. That inner golden light initiated the peak of the images. And we made the decision to maintain a bit of bewilderment about how the instruments work, because we prefer to see them as a vessel of love. The warm mahogany tones of the string instruments, that classic brilliance of the brass, created a really nice color palette.

After these moving stories, the final sequence with the featured students and artisans alongside LAUSD alumni, playing songs you wrote, Kris, is a wonderful grace note.

Arches: It's taking a risk to put a 9-year-old next to someone who played on “Jaws,” so it required a lot of consideration in composition and intentionality. But I'm always surprised by what musicians can do. They can play it instantly as if they have been playing it for years. It only happens in a handful of cities and that's why most of the scores are in Los Angeles for these emotional art forms.

Proud Foot: That historic gathering of generations of LAUSD musicians was probably the most memorable day of production I have ever experienced.

Work done on an instrument.

(Breakwater Studios)

Based on the reach of the film and the positive response from city leaders, is this repair shop, the only one of its kind in the country, better protected?

Arches: At City Hall someone said: “This space can never be closed.” So it's really gratifying that there has been such a reaction from the people responsible for making those decisions. Hopefully that will spread as they pass their jobs on to their successors and more people focus on how music is such an important part of the beating heart of Los Angeles.

Proud Foot: I think it is safer. But you can never say never. We hope that even questioning it will prove at least deeply unpopular. Defenders of the film are on every street in Los Angeles, as long as we can speak with one voice.

Work done on a metal instrument.

(Breakwater Studios)

What makes you return to the short documentary to tell stories?

Arches: We are in a time where people want to see something very quickly. So this is the space where you have the greatest impact, with a very small amount of resources.

Proud Foot: The short documentary has no commercial purposes. It is by far the most accessible, democratic form of cinema with the lowest barrier to entry. And in a time when so many millions of talented storytellers are kept out of our art form simply because of cost, the short offers a welcome entry to people around the world. We didn't do this to generate cash. We made this movie because we thought, “This is a story that we think people need to hear.” That's why we have it free everywhere, on YouTube, Disney+, Hulu, Instagram, everywhere.