“The End,” from director Joshua Oppenheimer (“The Act of Killing,” “The Look of Silence”), is a grim musical about perhaps the only six people left on Earth: an oilman and his trophy wife (Michael Shannon and Tilda Swinton), their bunker-born adult son (George MacKay) and the three helpers (Bronagh Gallagher, Tim McInnerny, Lennie James) invited to this underground ark.

Something horrible is outside. We hear allusions to a blood-red sun, a poisoned sea, and vultures. But this salt mine sanctuary features walls adorned with artwork and a table set for wine. and Champagne. These survivors have isolated suffering for more than 20 years. Still, they can't breathe.

Not in the literal sense. The cast has the lung capacity for more than two hours of singing, and the songs, for which Oppenheimer wrote the lyrics and composer Joshua Schmidt composed, are absolutely dazzling, accompanied by a humble charm. If a voice breaks, it breaks. Emotion takes center stage, backed by unyielding violins and trumpets and slinky melodies that jump an octave to hit surprising notes.

But there's not enough air here for everyone to have personality. All the characters have rigorous manners, as if they were imitating the mannequins from the old bomb shelter film strips of the 1950s. In the opening song, people enter the living room one by one, cups of coffee in their hands, and when they realize that everyone else is already humming about another perfect new morning, they join in as if to be polite. . “We fight together in the darkness / our future is bright,” they harmonize, keeping their backs as straight as a church choir.

The irony is obvious and for the first hour that's all there is. The confident tycoon, the shallow wife, the adored child who was raised so cloistered that he whistles Canary songs to a crab tank and tries to teach tricks to a fish. These aren't full characters, they don't even deserve names, they're just the clichés we'd expect to see dining on Dover sole while the rest of us are dead. (Also, the workers don't deserve much attention.) Oppenheimer and his co-writer Rasmus Heisterberg have given each family member a flaw that they sing about so incessantly that the running time could be cut by a third. We get it, life in the bunker lacks air. This house is so gray and cold that something has to break.

During the film's stiff, boring first stretch, the family discovers a strange young man, played by Moses Ingram, who has endured the apocalypse long enough to track down the source of his smoke escape. If you think that's implausible, wait until you see how this presumably miserable refugee, a girl who's never worn shoes before, not only arrives with TikTok-trained options about working-class rights, but seems unfazed by these opulent digs.

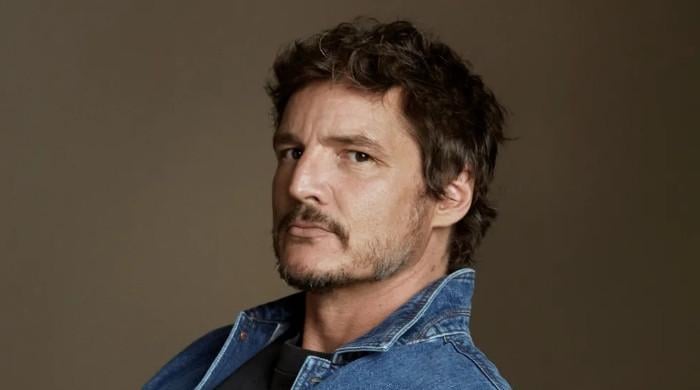

George MacKay and Tilda Swinton in the movie “The End.”

(Neon)

Ingram and MacKay start out as the kind of couple you wouldn't make even though they really might be the last fertile singles alive. But they like each other enough to sing their own duet, running through the salt mine with open arms. (Choreographers Sam Pinkleton and Ani Taj smartly choose liberated movement rather than precision.) Finally, the movie gets going and becomes something beautiful.

Oppenheimer is looking for something that gets right to the heart of what a musical is. Harmonize means to agree. It is a public display of solidarity, a pact to repeat the same deceptions like parrots. Here, only when these characters separate themselves do they sing their truth. Even then, they have felt so suffocated by lies that they can't always find the right words. In one number, Swinton, bright-eyed to show the cracks in her couture veneer, poses in a transparent raincoat as she bleats raw, howling noises that mingle with desperate strings. As for the naïve son, whom MacKay plays with red-cheeked, brain-worm precocity, during his wildest solo, he pushes his crotch and says, “Nyah, nyah!”

Lies are to Oppenheimer what the skeleton is to Da Vinci. He is obsessed with understanding how they work, how they evolve and adapt, how they end up controlling the way a person moves through life. When Shannon's patriarch insists that “oil drilling was just an excuse to build wind farms, clean water, and save chimpanzees,” he is rewriting history for an audience consisting only of himself and how he wants his son to do it. see. The magnitude of the destruction it has caused is vague and indescribable. We know there were riots because he insists there weren't.

Since our setting is the end of the world and all, we can estimate that his death toll exceeds that of Oppenheimer's groundbreaking 2012 documentary, “The Act of Killing,” in which former soldiers of an Indonesian death squad They recreated their past massacres to reinforce their conviction that they were the heroes. That powerful film sided with our desire to punish bullies. But when Shannon's fossil fuel magnate refutes that the rest of humanity also drove cars, well, he's right.

Perhaps out of a shared sense of guilt, Oppenheimer longs to give these sinners a chance to atone for their mistakes. Alone, they ask for forgiveness, as when Shannon scales a salt mound clutching a stuffed bird as if she thinks she's the heroine of “The Sound of Music.” Instead of condemning its characters forever, “The End” gives these plastic people the option to reclaim their humanity. That is which turns out to be torture.

This is a musical that treasures ridiculous imperfection, a scene where McInnerny does a funny little tap dance or the joy of Shannon's hyena laugh. Oppenheimer frees his script from the responsibility of explaining how this apocalyptic mansion works. The food stash, the waste disposal, none of that comes into play, and the characters are not at all curious about what's going on outside their cave. Instead, all the attention is focused on microchanges in people's moods, which, for such carefully curated characters, are as dramatic as a new ripple in a rock garden.

Only the Ingram home invader can be happy and sad at the same time. The girl cannot hide her emotions and that shakes this bunker to its foundations. The film around her is built on a fault line of contradictions: it is both lukewarm and insistent, a piece of decadent toast. But you leave thinking about the question that the characters never dare to ask or sing: What is the difference between being alive and living?

'The end'

Not classified

Execution time: 2 hours, 28 minutes

Playing: In limited release, it opens on December 6.