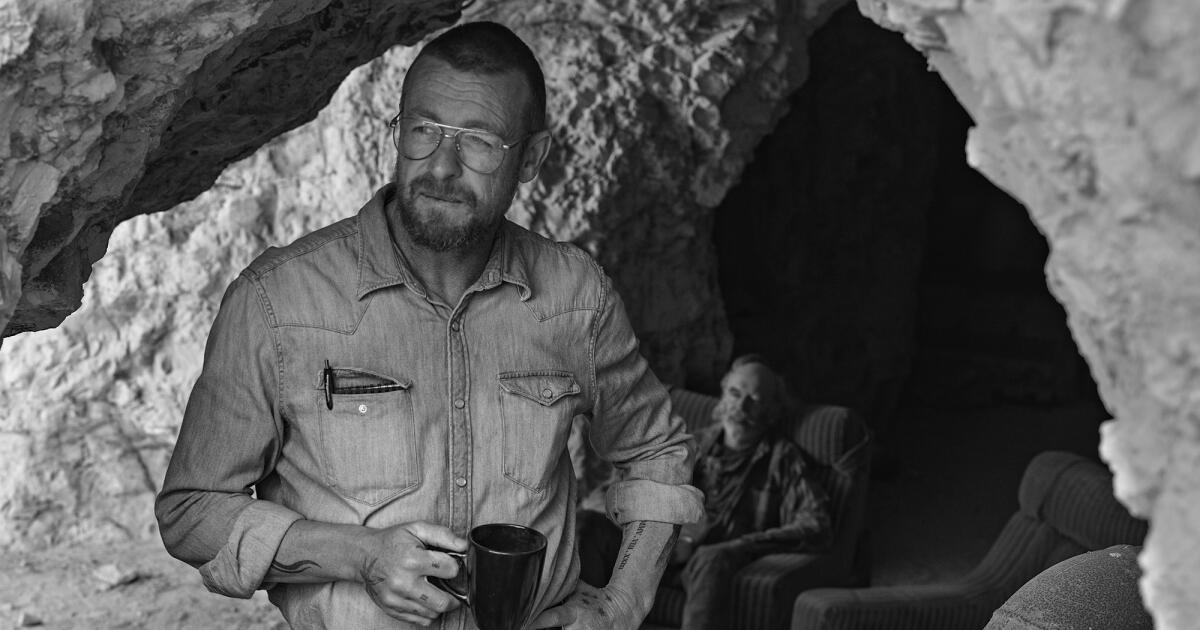

Daniel Roher’s 2022 Oscar-winning documentary “Navalny” helped make Alexei Navalny’s story more visible to people around the world, offering an intimate and personal portrait of a man known as an outspoken opponent of the president. Russian Vladimir Putin and for having survived a poisoning attempt.

That legacy deepens today with the shocking news of Navalny's death in a Russian prison.

Roher, born in Canada, was in Los Angeles on Friday and had just received a condolence phone call from Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau when he spoke via Zoom with The Times. Roher was shocked and still processing the news.

Was this outcome inevitable? Did you see that Alexei's story ended differently?

I did. In fact, I am surprised by how shocked I am, in light of the facts and despite the circumstances. I really thought Navalny would be one of those great defining figures of the 21st century. I think he will be, but I thought he would be sort of the mold of the politician who is in prison for 10 years and then emerges and galvanizes the country and becomes president and does all the things he wanted to do.

And in light of today's news, maybe I was naïve about it, but now I have to recalibrate and reconcile my view of this story. It's almost like, damn, this is how it ends? Is this how the story ends? But I just have to remind myself that no, the story has no end. This is just beginning. Navalny built an organization that is bigger than him. It is designed for continuity of movement even after his death. And it is my express hope that, in this time of pain, sadness and anger, people in Russia and around the world can transform those feelings into actions.

When was the last time you were in personal contact with him?

I think I sent him a letter in December. I don't know if it ever reached him. But before that, probably eight or nine months ago. There is a letter here, I keep it next to my desk. She sent me that letter after the Oscars and after I got married. His wife and his daughter were at our wedding. It was very meaningful for me. But it is somewhat challenging. I think something I will regret is the fact that I didn't get closer to him. As his life contracted and he existed in this gulag in these hellish conditions, my life expanded and all these wonderful things happened.

We got married and now we have a baby. And of course, thanks to the Oscars and all, my career is flourishing beyond my wildest dreams. And the legacy of that now is complicated. It's almost like this Faustian deal that I didn't sign up for, that I don't want. And I don't know what the legacy of this movie will be. I don't know what the legacy of this experience of my life will be, in light of Navalny's assassination. But I have a lot of gratitude for him, both for the moral courage he showed me and the world, and also for the deep understanding that if I didn't stumble upon him by chance and cross paths with him, I would. If I didn't have a baby, I wouldn't get married. My life would be radically different. And then I'm left trying to pick up the pieces of that and reconcile what these things mean in light of the circumstances.

And have you been in contact with your wife or family today since the news broke?

I have not. I sent [Alexei Navalny’s daughter] Dasha Navalny a message that just said I love you and I'm sorry. I don't know what else there is to say right now. This is like the eye of the storm of grief, the shock that comes when you lose someone and try to work through those feelings. And I want to give space to his family. I'm sure they are being flooded from all over the world. This event is shocking, disturbing and simply devastating.

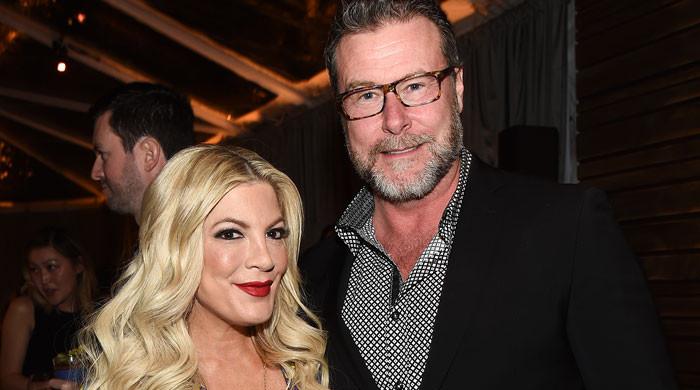

Daniel Roher accepts the Oscar for “Navalny” at the 95th Academy Awards in 2023.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Many people have already been sharing a moment. online from the doctor when Navalny He says, “If they decide to kill me, it means we are incredibly strong.” Today, do you think that is true?

I do, yes. I mean, the only reason they murdered him is because they were terrified of him. Putin is a very small, insecure little man, and the walls are closing in, and I think he feels the pressure that is starting to build. In Russia there will be elections in two or three weeks. Navalny has been his normal self, brooding, outspoken and agitating. And for some reason, the regime thought now is the time.

The bold and brazen nature with which Alexei was murdered is a middle finger to the world. And I am hopeful that his followers can channel, as I said, the anxiety, the fear and the deep sadness of this moment into action. Let's redouble our efforts. I wonder what he would think or say Navalny if he were here. And it's something like: “Don't cry. Let’s have a shot of vodka, raise a glass, and then get back to work.” There is much we have to do in light of this brutal dictatorship. I hope that's what people think today.

Was his death something you and he talked about often? Aside from that moment in the documentary, did you have any other conversations about what would happen if he was killed?

It's kind of uncomfortable. He and I became friends and it's awkward to ask a friend to hypothesize about his own death. The question of his mortality haunted all of our interactions, everything he did when it came to life outside of filming. He was more eager to talk about politics or learn about film, something I could teach him a little about.

But when it comes to talking about life and death, we save it for the cameras because it's so uncomfortable. I feel uncomfortable asking you these questions, but I am doing my best to diffuse the awkwardness and ask you these questions on behalf of the world. And today they are repeated on the radio and in the news around the world just because of how prophetic they seem. But I didn't imagine it would come true. Like I said before, I didn't want that to be the end of the story. I wanted it to be a good sound bite for our movie.

One thing I'm thinking about today is our movie. I used to tell people it's a comedy, it's funny, he's funny. I don't think it's a comedy anymore. And the legacy of the film will inevitably change in my own head, and I'm still coming to terms with that.

I think people will definitely turn to the film today and in the future. Days and months come. What would you hope they get out of it? hHow do you think that movie Can it change for you?

That is a good question. I don't know how his legacy will change. I don't know if I'll ever be able to see him again. I loved seeing him up there. And I remember this extraordinary moment in my life when, by chance and circumstance, I was faced with this man and the challenge and the opportunity to tell his story. And now it's almost like it's a piece of history. Plays as a commemorative piece. And that is difficult and unusual. And I think I'm still trying to process what can't be processed. And it will take me a long time to be able to fully articulate how this changes work.

But I'm less interested in my perception of the film than in how Navalny's death changes the world. She feels like the light has gone out. That's what I'm thinking about today. And I am hopeful that someone will take up the torch and the journey will continue and his followers will continue and his staff will continue the mission and the fight. And Navalny's death is not in vain. And the beautiful Russia of the future, for which he lived and died, will arrive soon.

Is there any personal moment or memory you have of him that comes to mind today??

I really liked laughing with him. I think the reason this movie works so well is our shared sense of humor. That was kind of like our common language. On paper I should never have made this movie. I'm a Toronto boy. I have never been to Russia. I do not speak Russian. The only thing I knew about Russia was Russian hockey players. And I think the reason I was able to connect with him is because we both have a sense of humor and that comes out in us, kind of like making fun of each other mercilessly.

My favorite anecdote is that, for those who know me, I always carry a sketchbook with me. I'm always drawing, painting and writing things. It's to help me deal with my ADHD. And he didn't really understand. He saw me drawing and said to me: “Daniel, what's wrong with this notebook?” And I explained to him that it's for my ADHD and I just draw everything and it helps me focus. And he turned to Maria, her number 2, and said, “Oh, it's so good that we hired a special needs director.” And I think that anecdote really sums up our relationship, the nature of our relationship. And I think that energy comes through in the film. In the first moment of the movie, I ask him a question, he rolls his eyes at me, and the movie begins. And that's how I remember our relationship.

When he was at the Oscars, he talked about himself as if he had taken on the role of what he called brand ambassador Alexei Navalny. Is that a role? Do you think you will continue playing?

Absolutely. Like I said, I come from downtown Toronto. I never thought life would turn out in such a way that I would be delivered to the guy's door and end up working with him and doing this. You couldn't foresee that happening. But of course it happened and all of a sudden I'm traveling the world with this movie and audiences are responding to it and it has this energy of feeling. And I'm in the middle of the storm. And what I'm trying to do more than anything is keep his name in the global consciousness, do everything possible to deter the regime from assassinating him. For us, that meant keeping his name relevant to him.

As we know now, that was not successful. But I think the mission of the film now changes. It is now a legacy piece and will exist for history, so that people will never forget it. And here we have a film that tells the story of this extraordinary man and his mission, his family and his sacrifice. And now it exists for history, which is kind of surprising.