In “Inside the Episode,” the writers and directors reflect on the making of their Emmy-winning episodes.

“War,” the fourth season finale of Netflix’s royalist drama “The Crown,” is chilly.

And that's not just because it takes place right before and during Christmas.

This part of the story of Queen Elizabeth II (Olivia Colman) and her ilk is about the marriage that is destroying the lives of her eldest son and heir apparent, Charles (Josh O'Connor), and his long-suffering wife, Diana. (Emma Corrin). It's also about Parliament finally bending its Iron Lady, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (Gillian Anderson).

In a more relatable sense, as Jessica Hobbs' Emmy-winning direction shows, it's also about that icky, uncomfortable, self-conscious feeling people get when they're forced to be in a room where they know they're not wanted. In different ways, Hobbs focuses the camera on the ostracized women of Anderson and Corrin as they try to keep their upper lips stiff even though every hair on their body is firm and they count down the seconds before they can retreat to the privacy of their rooms. to cry. she, she screams she and collapses on the bed.

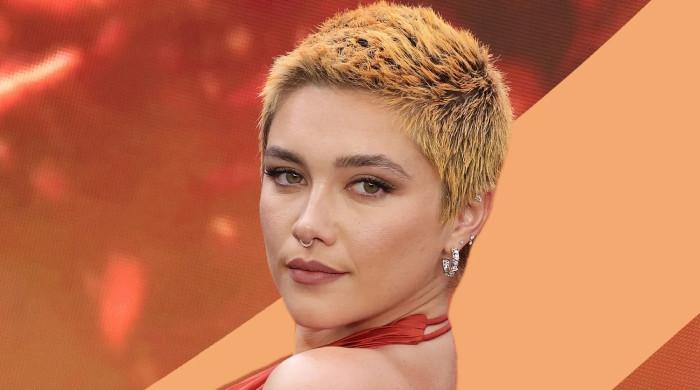

Jessica Hobbs won an Emmy Award for directing a drama series for the season four finale of “The Crown.”

(Gareth Cattermole/Getty Images)

Hobbs, who has directed several episodes of the series created by Peter Morgan, tells The Times that there were a few reasons he asked for this episode. One is that he likes the complete feeling of the season finale, when all the stories come together. Another is that this would be the final episode with this cast, as the show rotates between younger and older actors every two seasons to tell the stories of the real people it represents. And, he says, this wine had a lot of feminine power.

“I felt like that particular episode was very female-centric,” she says. “And I wanted to present those women's stories in a way that perhaps reflected her isolation as strongly as I felt it. We knew her public stories. It is the behind-the-scenes stories that I was interested in reflecting more.”

Here, Hobbs thinks about the episode's color palette, the sense of betrayal these women felt, and how to recreate the story while respecting those who suffered (such as Diana's well-documented eating disorder).

There seems to be a lot of blue in this episode. There is an icy blue coming through the windows as we prepare for the morning. In the end, when Diana arrives for Christmas with royalty, she stands out in a blue tartan suit, while everyone else wears more muted colors…

For the opening scenes, cinematographer Ben Wilson and I wanted to create an early-morning blue feel, which would actually occupy the way you'd watch the episode. This was the end of many things. The first man you meet [Paul Jesson’s Sir Geoffrey Howe] The ball is about to start rolling. He will initiate Thatcher's downfall, which will take the queen to a different place. And he begins to expose Charles and Diana's relationship.

We were entering a whole winter period. And that's why we wanted winter, Christmas, low light, unique fountains. It was something that affected the kind of palette of the entire episode. It wasn't summery or bright.

Plus, that family has a uniform. For a while, Diana would be okay with that. And she very deliberately in those last few years began to dress in a way that was most comfortable for her. [with] For herself. And we really wanted to reflect that. If she had maybe taken two steps forward and said, “Hello,” someone would have answered her. But there was like this gulf, this abyss, that existed there and [costume designer Amy Roberts and I] I felt like the costumes really reflected that.

The episode also begins with a peripheral character's morning routine. Geoffrey Howe is not a name immediately known to outsiders, but it is his speech in Parliament that brings down Thatcher. You also photographed her reacting to her comments from a lower angle and up close, as if to see if we caught her angry.

It's really lovely to start with a character you don't know because… you have the full concentration of the audience because they're trying to figure out what's going on.

And I did two things in [the Parliament] scene. I sat under her because I wanted to feel her vulnerability. And I shot her from her point of view. He wasn't looking at her and she never fully turned around. Gillian and I talked about this quite a bit. I think you are very aware when a speech is said about you that it is not going to come out well, and for me it was very important to portray her physical appearance by keeping her back to him.

You also follow his slow walk and car ride home before he finally goes up to his room. But the camera only looks at her crying there. It's like you're still giving him some dignity and privacy.

it really is [several filming] locations, so congratulations to Gillian. She is in the car and walks among her assistants another day. And then I went upstairs that same day, and then into the hallway and into the bedroom on the fourth day. So for her to maintain that composure of where she was emotionally, I thought she was great. But I wanted it to feel like it was a procession, that she was just going to the smallest, quietest space she could find and that was the only place where she could really show her emotions. Instead of being voyeuristic, we were being respectful of the privacy of the moment.

This also speaks volumes to people in power, particularly women, who are not allowed to show vulnerability.

Gillian and I talked about this. We felt like there were two places in the episode where she could show vulnerability. That was rather a horror that landed on her. In the meeting with the queen, [later in the episode]where she comes to ask him to dissolve Parliament, we wanted to make sure we created a balance between those two, that one didn't steal from the other.

This scene with the queen is one of many in which people are sitting and talking. Obviously, what they say is important. But as a director, how do you film them in such a way that they keep the audience interested?

A lot of it has to do with making sure the camera reflects the state and space around them, and that we allow time to let the tension build. And it was also choosing when to allow people to look directly into each other's eyes and when to observe them more from a slightly more profile angle. We give ourselves a lot of time to take the different shots that we know will develop in that dynamic.

I love Thatcher's rigidity. Curiously, in that second scene where she cried, she wasn't expecting it. She didn't expect her to do it. Olivia certainly didn't. And Olivia is very empathetic. I tell him: “Don't be nice to her. When we finish filming, you can get out of her and give her a hug.”

It was the way the words hit her in that moment, that they landed on her with such force that she felt like it was finally over. Whereas before, going up the stairs is a moment of anger and a feeling of brutality from all those men who approach her. This was her going with another woman and just [more or less saying]”It's done. Game over.”

In one of these conversations, Queen Elizabeth awards Thatcher the Order of Merit. I don't know if what was said between these two women is accurate. But it's interesting that you held the camera on the medal box, which Thatcher had left on the table. Is that something subtle?, “AND“Aren’t you done with me yet”?

Nobody knows what happens in private audiences with the queen. So those are always made up. …That's why it's always a great place to hang important dramatic scenes. … We worked very hard to find the queen's discomfort in her relationship with Thatcher, but that she wanted to give some recognition to another woman who had been in a very high position for several years and in a difficult way.

We were still arguing about [how to end] in post-production. She had said goodbye in one of the takes and I took it out. I really love how awkward it is, the silence at the end.

We had many conversations about it. [leaving the box] in the room. We decided there were people who would take care of that and deliver the box to him. I also liked it from a visual point of view. Particularly with female characters, like if someone comes out and has a really elaborate hairstyle, I'm like, “Who did that to them?” In terms of story, I'm always looking at what the logic is for what their appearances are like.

You show Diana's bulimia. But, like the Thatcher scene, it is handled respectfully. Were there conversations about how much of her eating disorder to show, both to honor her and any audience members experiencing this?

We had a lot of conversations about it and a lot of research and consultation. It's something we knew about her and it's also something that's not uncommon. I felt (and I know Emma also felt very strongly, as did the cinematographer, and we also talked to Peter about it) that she wanted to accentuate the loneliness of her, the isolation of her, rather than the energy of the situation. . act itself. The times we show it, you hear it and you are aware of it. But we actually filmed it on a mirror as part of the bathroom cabinet. And then she slowly sat down by the bathroom as we approached her. I felt like the visceral sound of her was enough for people to understand but also for them to experience the desperate sadness in terms of what was going on with her emotionally.

And then the second time, we just built it in a way that we felt like we could visually tell the story that she was done. She had had an argument with Charles that led her to almost a new way of being. And that's why too [the episode is] called “War”. When you get to the end of the episode, he's now been told, “Now I'm going to fight my corner.”

The episode also has to re–create another well-documented event: Diana's trip to Harlem, New York, where she became one of the first public figures to embrace AIDS patients. How do you do that without it being a parody?

I think we tried to find a line where, hopefully, you had the emotional experience. One of the doctors we spoke to who was there at the time said that he was smart enough to know that, by using his media presence, he would draw attention to something he needed to draw attention to. I also loved the child [she hugs] have some kind of agency and not just be a figure in a bed.

The fourth season of “The Crown” ends with Diana agreeing to be part of the family's Christmas photo.

(Ollie Upton/Netflix)

The episode ends with Diana agreeing to be part of the family's Christmas photo. However, she is wearing a much more modern black velvet evening dress and stands out from everyone.

He dresses as if it were his own funeral. What was so beautiful was [costume designer Roberts and I] she talked about the exposure of her back and how exposed she felt. That dress allowed me to photograph her from behind her, just to have that visceral understanding of how exposed this woman felt in this room full of people who were supposedly family.

The Queen's love for corgis is well documented in both “The Crown” and in royal photographs. Is there an art to tossing corgis?

There are a lot of corgis. Prince and Lily are the two protagonists, but they are very problematic. Some of the others were good. I mean, you don't see the points in between where some of the dogs get a little angry. …I loved the kind of dramatic nature of working with them and the fact that they could change the scene slightly.