And so the two weeks in which I take an interest in athletics every four years have come to an end, with a ceremony to mark the occasion. There were many ceremonies along the way, of course, and the Olympic Games are themselves a kind of grand-scale ceremony, a ritual by which Earth's athletes measure their worth, though they are obviously busy with international competitions in the years between the games, winning medals and trophies and setting world records. But the world has agreed that this is the Big Show, as the world agrees on almost nothing else.

Since this is technically a TV review, let me say before I get to the spectacle that what happened between the opening and closing, as far as viewing goes, was exceptionally well presented — at least if you watched it via Peacock. (I can’t speak to NBC’s broadcast coverage, aside from the opening ceremony, where commentary was intrusive and uninformative, and the closing, which I’ll get to later.)

It was a platform from which one could launch in any direction, a well-executed interface that allowed one to follow any sport in any way, all of it, at any time, from before the start of an event until long after the end, in what I call the hug round. So many hugs! All that goodwill and affection, not just between teammates but between competitors, representing the diversity between and within nations, whatever the peculiarities of their individual governments and nativist movements. It’s a world you want to live in. (The Olympic spirit: it’s not just about gold, silver and bronze.) An illusion, perhaps, but as Marlene Dietrich said, “You can’t live without illusions, even if you have to fight for them.”

One of the five giant Olympic rings is lowered into place during the closing ceremony of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games at the Stade de France.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

As for Paris, the staging of the Games—and “staging” seems the right word—in and around the city center seemed inspired, somehow both very old and entirely new. True, there were parts and people of Paris that remained hidden, if not intentionally hidden. But the construction of temporary open-air stadiums beneath the Eiffel Tower, on the Place de la Concorde, and in the Gardens of Versailles demonstrated that a host city might have something to show the world outside—literally outside—its great stadiums, something essential to the spirit of the place. (Although, with its many parks and large public spaces, it might be better suited to the task than any other city.) Putting swimmers in the Seine may not have been the healthiest idea, but it had its look. Races held on crooked cobblestone streets, packed with spectators, were doubly exciting for being held on crooked cobblestone streets, packed with spectators.

Finally, the closing ceremony was almost by definition a disappointment, given that the games were over (though not yet “officially” over) and that all the races had been run, if only just (the winners of the women’s marathon received their medals during the ceremony). But given artistic director Thomas Jolly’s idiosyncratic opening show, set on the Seine, one might have expected something interesting, if not self-explanatory. If the opening was an often confusing but certainly exhilarating cavalcade of images and events, the closing came across as a unique, stately and snail-paced piece of theatre, rather like Robert Wilson directing Cirque du Soleil. It was framed by a prelude at the Tuileries (where a choral rendition of Edith Piaf's “Sous le ciel de Paris,” by the way, accompanied French swimming champion Léon Marchand, who took a bit of the Olympic flame to pass to us) and a Gallic version of a Super Bowl halftime show, anchored by the band Phoenix.

Alain Roche plays a piano hung vertically during the closing ceremony.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

The centerpiece was all about the founding and revival of the Olympic Games, and began with a golden winged figure descending to an abstract Earth to meet, after a solo dance passage, the silver horseman and the still mysterious hooded torch runner we saw at the opening ceremony, the latter carrying a pole from which the Greek flag unfurled. Voyager discovered the long-lost Olympic rings. Opera singer Benjamin Bernheim, in a robe made of recycled VHS tapes, sang the “Hymn to Apollo” accompanied by Alain Roche, playing a piano suspended in the air, perpendicular to the ground. Numerous grey figures unearthed giant rings, which rose into the air, one by one, while performing tricks on their inner scaffolding. An (inflatable?) replica of the “Victory of Samothrace,” like the famous one found in the Louvre, rose from the ground. The lights in the stands, coming from wristbands worn by the audience, produced gigantic animated athletic events like those found painted on a Greek vase. The five airborne rings were arranged in the familiar Olympic pattern.

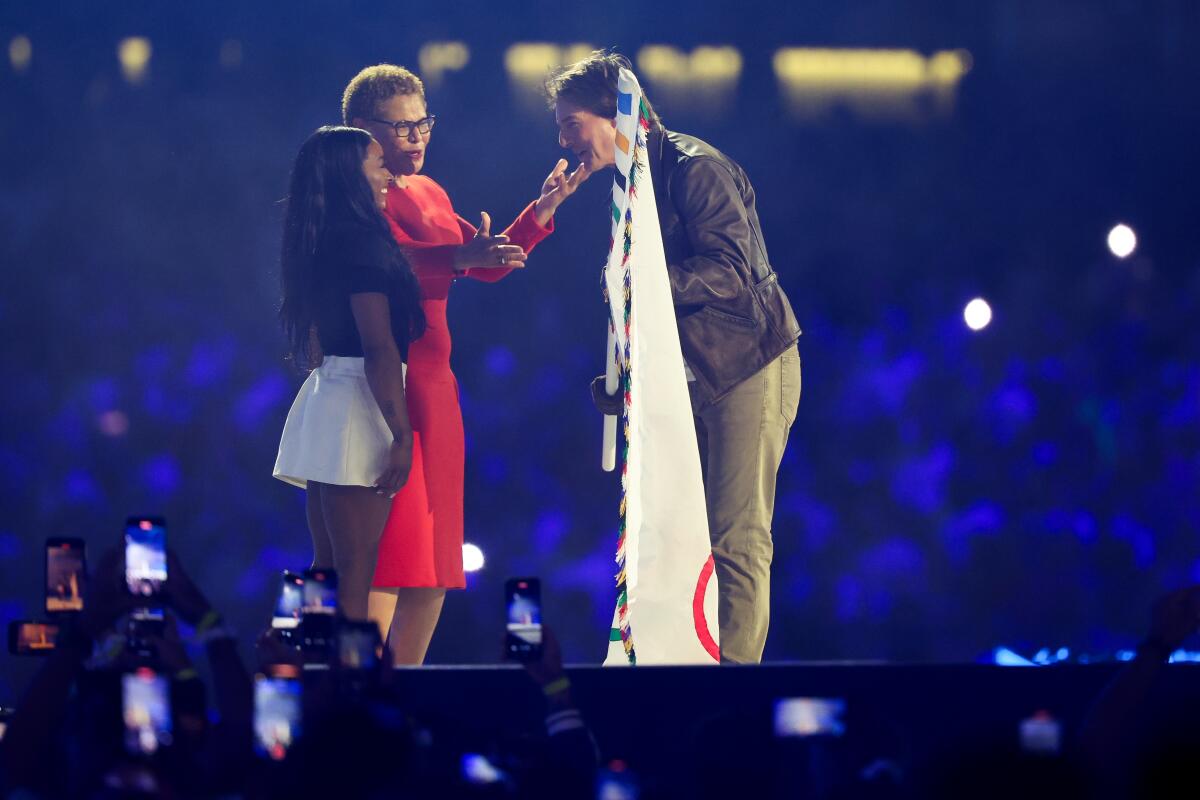

Then came the fireworks, the pop spectacle and the protocol: speeches (beautiful, generous), declarations, the lowering of the Olympic flag and the handover of the games to the 2028 host. HER, sporting a white Stratocaster like the one Hendrix played at Woodstock, performed “The Star-Spangled Banner,” proving once again that it is a song best performed by an R&B singer. Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo handed the flag to Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, accompanied by beloved American gymnast Simone Biles, and the spectacle became shockingly Hollywood.

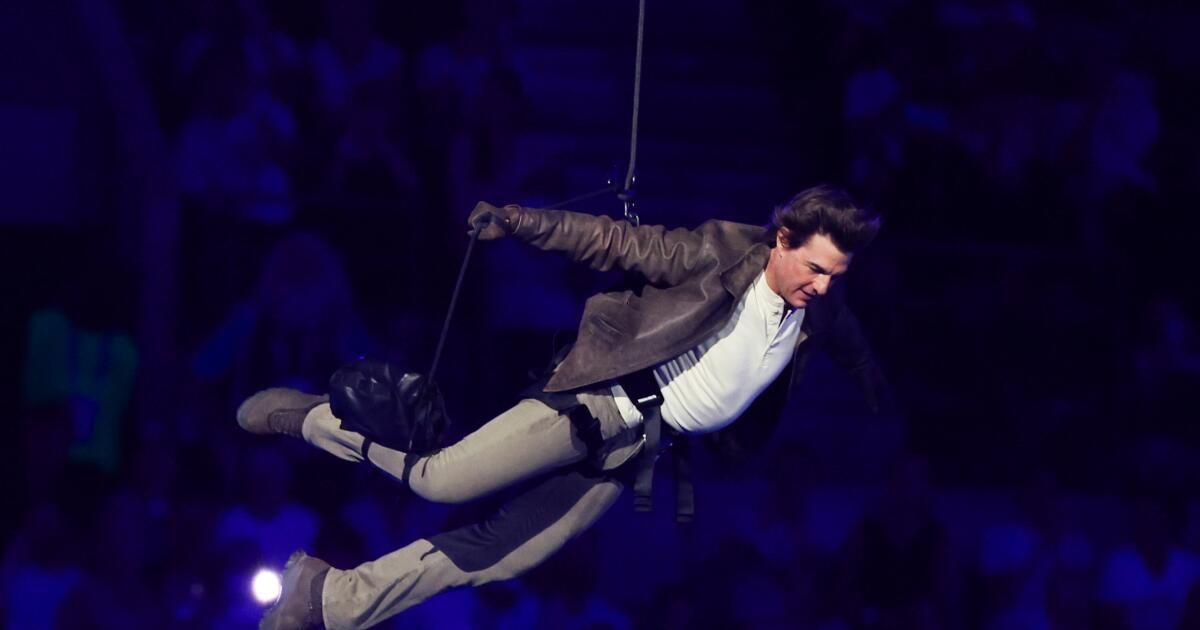

Tom Cruise receives the Olympic flag from Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass and gymnast Simone Biles during the closing ceremony.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Tom Cruise, whose status as an international superstar was enough to justify his presence, rappelled into the stadium, grabbed Bass and Biles’ Olympic flag and carried it away on a motorcycle, exited the Stade de France, and entered a filmed scene in which he boarded a cargo plane, skydived into the Hollywood Hills, and placed three additional O’s on the Hollywood sign to create an image of the Olympic rings. He passed the flag to a series of Olympians: first, to cyclist Kate Courtney, who passed it to Olympic sprinter Michael Johnson, who passed it to skateboarder Jagger Eaton, who arrived in Venice Beach. Then, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Billie Eilish, and Olympic ambassador Snoop Dogg performed in another filmed scene (shot in Long Beach, actually) that looked like nothing more or less than an MTV “Spring Break” special. (I’m pretty sure those palm trees were trucked in.) Aesthetically, it was like leaving a dark movie theater after a mysterious foreign film and walking into the bright sunlight of a noisy American shopping mall.

Fortunately, things didn't end there. We returned to the darkness of the Stade de France, where French singer Yseult performed an unusually subtle and sensitive version of “My Way,” whose English lyrics are by Paul Anka but whose music, by Jacques Revaux, is French. (The original, “Comme d'habitude,” has lyrics by Gilles Thibaut and Claude François.) In case you were wondering, why “My Way”?

The commentary was no less essential with the addition of Jimmy Fallon, who also has a show on NBC.

Yseult performs “My Way” during the closing ceremony.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)