This election year has been so full of outsized stories that reading the news can feel like reading a thick novel. An assassination attempt on a presidential candidate. A late retirement of a sitting president, followed by the immediate rise of his successor. We live, as the old expression wishes (or curses) us, in interesting times.

Not to be outdone, Emmy season is filled with its own political intrigue, and not just the kind that usually accompanies awards competitions. As the country prepares to elect a new president, it seems fitting that some of the most nominated series are driven by the art, strategy and outright combat of politics. In television, as in life, it is a full-contact sport that requires subterfuge and a constant shifting between public and private identities. In the most extreme cases, such as the most awarded show of the year, politics is a matter of life and death.

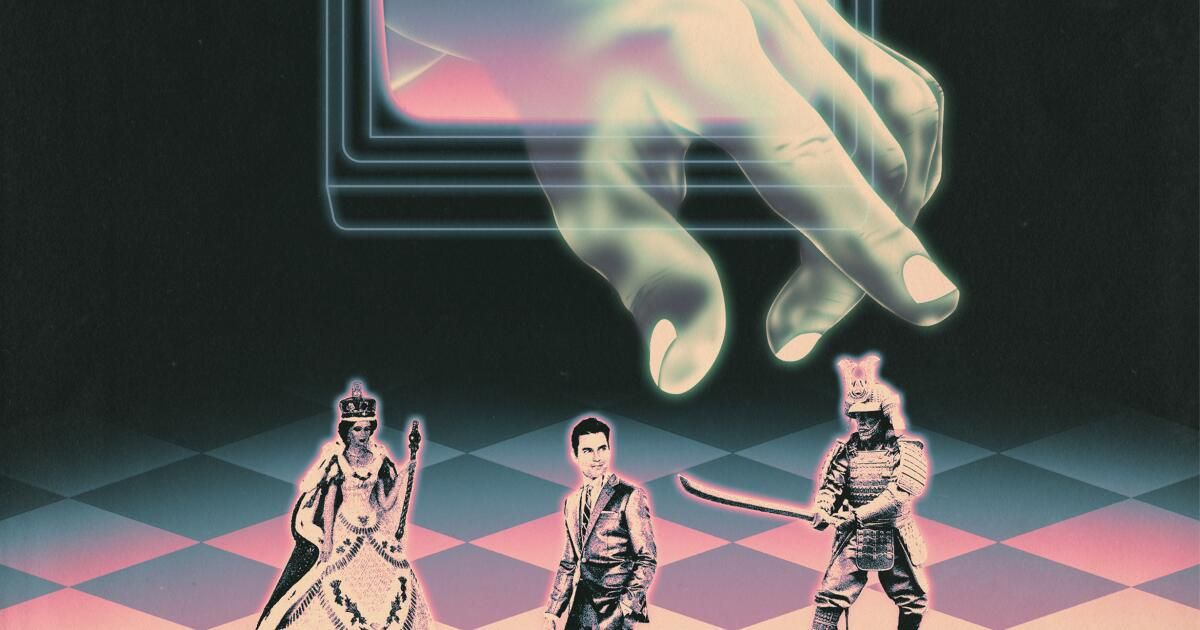

The political game in “Shōgun” is so intricate you might need a scorecard, or at least a good summary, to follow it. Nominated for 26 Emmy Awards, FX’s superb drama about power struggles in feudal Japan revolves around Lord Yoshii Toranaga (Emmy nominee and series producer Hiroyuki Sanada), a brilliant warlord seen as a threat by his peers on the Council of Regents. Toranaga’s rival regents concoct a plot to oust him from the Council and consolidate their power. But Toranaga has an ace up his sleeve. His name is John Blackthorne (Cosmo Jarvis), an Englishman Anjin (or pilot) who has washed ashore on the coast of Japan, Blackthorne becomes Toranaga's most valuable pawn in the three-dimensional chess game that follows.

On television, as in life, politics is a contact sport that requires subterfuge.

The strategy comes to a quietly operatic climax in Episode 8, “The Abyss of Life.” Toranaga has surrendered to his Council enemies and accepted his fate. Or has he? His loyal cabinet, led by Toda Hiromatsu (Tokuma Nishioka), refuses to believe their general has surrendered. Surely, this must be a ruse. Hiromatsu prepares to commit seppuku, or suicide by disembowelment, if Toranaga really plans to surrender. Will Toranaga let his old friend kill himself to perpetuate what could be a carefully constructed ploy? The scenario plays to the series’ greatest strength by wrapping a tense political struggle within a purely human drama.

Meanwhile, Netflix’s “The Crown,” which bows out after six seasons with 18 nominations (and a total of 21 wins since its 2016 premiere), continues its smart dramatic study of competing public and private political images. The topic has been a central one since the series began, with the ascension of Queen Elizabeth II (then, two-time Emmy winner Claire Foy; now, Emmy nominee Imelda Staunton) to the throne. The sixth season focuses largely on the death of Princess Diana (Emmy nominee Elizabeth Debicki), but it also has its share of less lethal royal politics.

For example, Prince Charles (Emmy nominee Dominic West) seeks his family’s approval for his fiancée, Camilla Parker Bowles (Olivia Williams), even as his entourage encourages him to publicly smear his ex-wife, Diana. Future Prime Minister Tony Blair (Bertie Carvel) attempts to carve out his own slice of influence with the royals — a dynamic that dates back to Season 1, when aging Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Emmy winner John Lithgow) sought to ingratiate himself with Elizabeth and her father, King George VI (Jared Harris).

This first Churchill story also dealt with circumstances that should be familiar in America in 2024: an elected leader facing enemies who consider him too old to do his job. And it addressed a question that largely defines British politics and recurs throughout the series: What is the role of an elected official in a society that cares first and foremost about its monarchy?

Matt Bomer, left, and Jonathan Bailey star in “Fellow Travelers,” a limited series whose juiciest political battles take place in the 1950s, at the height of McCarthyism.

(Ben Mark Holzberg/SHOWTIME)

Finally, and closer to home: fear and hatred in America and in “Fellow Travelers.” The Showtime miniseries, which received best-acting nominations for Matt Bomer and Jonathan Bailey, spans decades of its central characters’ lives. But its juiciest political battles are fought in the 1950s, at the height of McCarthyism, an era of blatant opportunism and fearmongering that still permeates American electoral politics.

Based on the novel by Thomas Mallon, the eight-episode series “Fellow Travelers” sits at the intersection of the political and the personal, and asks whether the two can be separated. Hawk (Bomer) is an ambitious State Department employee who helps Tim (Bailey) land a job with his hero, Sen. Joseph McCarthy (Chris Bauer, wearing a heavy prosthetic limb). They begin a tempestuous relationship, marked in large part by Hawk’s fierce desire to remain in the closet.

Tim, the conservative gay, is a romantic. Hawk, who leans left in his political allegiances, is a careerist shark. Both live under a reality of 1950s life: coming out means being banned from public life. Later, they live under a dark shadow of 1980s life: the AIDS epidemic.

The public/private schism drives “Fellow Travelers,” which has its own personal connection to the current presidential race in McCarthy’s hidden henchman Roy Cohn (Will Brill), a former mentor to Donald Trump who was disbarred in 1986. The series can be seen as a drama about the cost of selling one’s soul and whether redemption is possible after the transaction is complete.

Politics aren’t pretty in “Fellow Travelers,” which means it has a lot in common with the here and now. You enter the arena at your own risk. You can watch through clenched teeth. On TV, anyway, you have plenty of options.