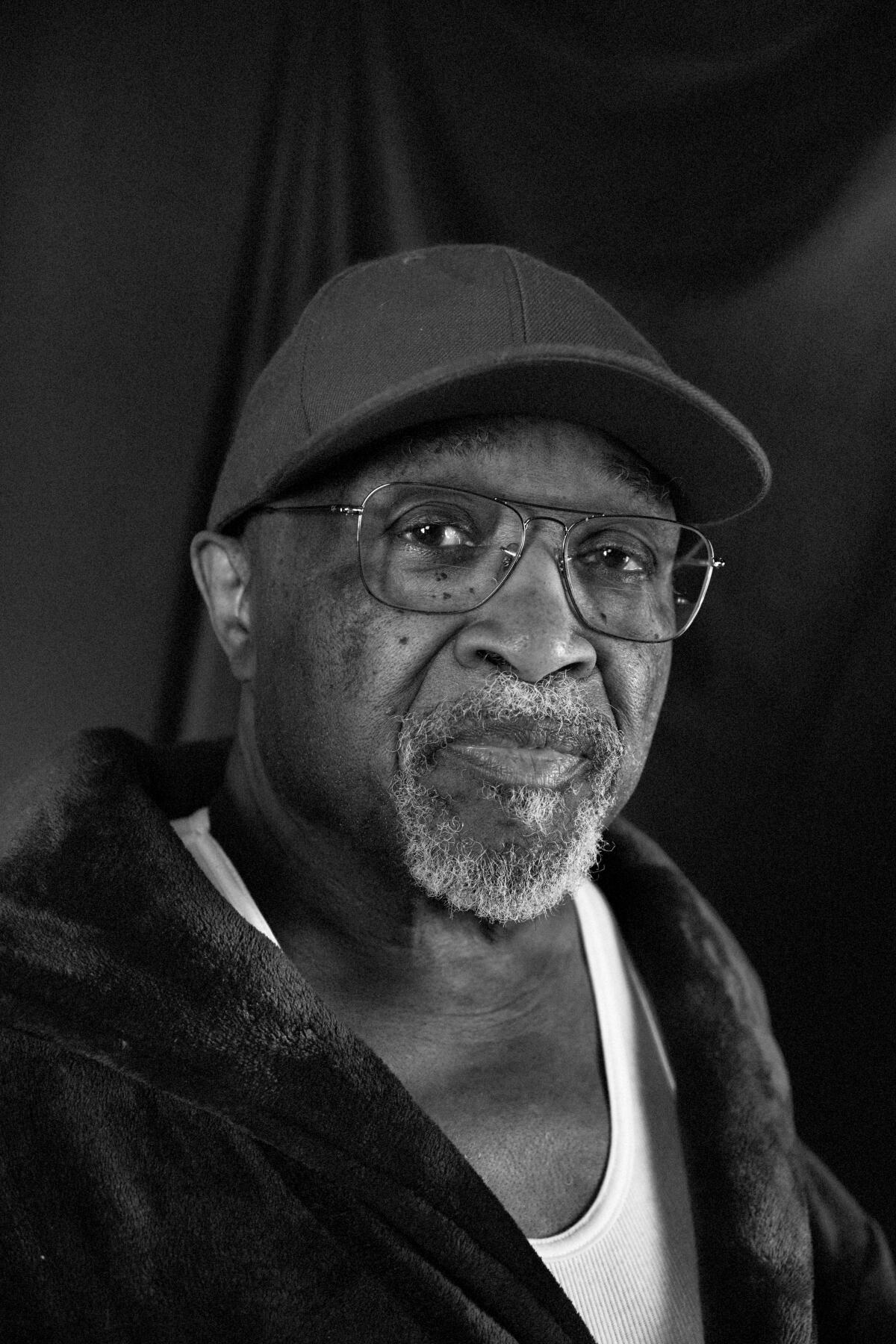

Jerry Williams Jr. has a simple reason for deciding to record a bluegrass album: he doesn't know how much time he has left to do it. At 81, the cult R&B singer, songwriter and producer, best known for his sleazy, wisecracking alter ego Swamp Dogg, can't take anything for granted.

“I figured at my age I don't have much time left to be running around here on Earth, no way,” Williams says over a Zoom call from his home in Porter Ranch. He leans back in his office chair, hands crossed in his lap and a baseball cap tilted atop his head. The blinds are closed behind him to block out the afternoon light.

So Williams says, “I'm really going to go where I feel.”

“Blackgrass: From West Virginia to 125th St,” Williams’ 26th studio album as Swamp Dogg, continues a renaissance that began in 2018 when he teamed up with producer Ryan Olson for the acclaimed “Love, Loss, and Auto-Tune.” ”. Gone are the blatant vocal effects shown on that and his last album. “I need a job… so I can buy more Auto-Tune,” replaced here by banjo, fiddle, and rawer, earthier narration.

There's the trademark sex and humor Swamp Dogg is known for on early albums “Mess Under That Dress” and “Ugly Man's Wife” and guest spots from Margo Price, Jenny Lewis and Vernon Reid, plus some of the best modern-day bluegrass pickers, including Chris. Scruggs and Sierra Hull. There's even the occasional love song, in which Williams's graying voice tinges anguish with weary affection.

“I wanted to get out of where I usually am musically and make an album for me” Williams insists, in his slow, catchy drawl. He points to the 1970s psychedelic funk classic “Total Destruction to Your Mind,” his first as Swamp Dogg, as the only one “made for me, by me” so far. “That's what I had in mind,” he says. “As I was doing this, I said, 'Well, no one likes it, no one likes it.' But it was time.”

That excitement was palpable from the first demos, according to collaborator, band member and roommate Larry “Moogstar” Clemons. “I was amazed,” says Clemons, who has lived and worked with Williams for more than 15 years. “It was like, wow, he's really excited. This is something you've been waiting for. You did it. You did it now.”

Williams has always dreamed of making an album like this. Since he was a child in Portsmouth, Virginia, in the 1940s, he was enamored of country and bluegrass, which he often heard on Norfolk radio station WLOW by DJ Sheriff Tex Davis or on records his grandfather brought home. to home. The first song he learned to play was Red Foley's version of “Peace in the Valley.”

Swamp Dogg put together his new bluegrass album, “Blackgrass,” with the help of his extensive back catalog: supposedly 2,000 songs he has written, recorded or produced.

(Sam Müller / for The Times)

“I just loved it. I loved the music, I loved the tempos of the mandolin and… I also loved the violins,” Williams says. “To me, it was just good music. And it was mixed with rhythm and blues. Between listening to Rhythm and Blues and Bluegrass, I always wanted to put them together.”

The new album does so with the help of Williams' extensive catalog (reportedly 2,000 songs he wrote, recorded or produced), including reinterpretations of songs he originally wrote for artists like the Commodores and the Drifters. There are also covers of songs he loved in his childhood, such as “I Gotta Have My Baby Back” by Floyd Tillman or “Have a Good Time,” a pop hit by Tony Bennett in 1952.

“If it was a hit once, no matter how long ago, it can be a hit again,” Williams believes.

Williams has had hits in the country scene before, although he never received the credit he was due. Most notably, he co-wrote “She's All I Got,” which reached No. 2 on the country charts with Johnny Paycheck in 1972. But as a black artist, he was caught between two worlds: when he attended that year's Country Music Association. . awards in Nashville, he was initially mistaken for a member of the kitchen staff.

Margo Price, who duets with Williams on the “Blackgrass” cut “To the Other Woman,” which she originally wrote for Doris Duke, was a devoted fan long before she learned of her country roots.

“He's always thinking about music, always reinventing himself, and he's super fun and down to earth. And it has great stories,” he says. “Just hearing what he went through as an artist, especially as a black artist, trying to break into the country music world and his experience at the CMAs: he's been through a lot and he's really an unsung hero.”

Still, Williams says, country was at the root of many of the songs he wrote over the years, even when they had R&B or soul guise.

“I was really leaning on country when I wrote them. It's just that once I put all those horns on him and [other touches] There, he cornered country, which is what he wanted to do,” Williams says. “I liked the country feel, but I knew black radio wouldn't touch it for a 10-foot pole.”

Calling the new album “Blackgrass” was a conscious attempt to reclaim the heritage of bluegrass and reframe its importance to black listeners.

“I wanted black people to know that when they made fun of bluegrass, it was Africans, not white Africans, [but] Black Africans: that brought that [music] to this land,” he says. She scoffs at anyone who dismisses it as “country music,” saying, “To me, that's prejudice.”

Throughout his career as Swamp Dogg, Jerry Williams Jr. has approached racial issues from a provocative and often controversial point of view.

(Sam Müller / for The Times)

Throughout his career as Swamp Dogg, Williams has made a habit of approaching racial issues from a provocative and often controversial point of view. Some of his best-known songs have titles like “I've Never Been to Africa and It's Your Fault” and “Call Me [N—],” which he claimed featured a member of the Ku Klux Klan playing the banjo.

“This really bothers people, because I guess that's what kept my career at a certain level,” he says with a smile. “They tell me: 'You say [the N-word] too much.' Look, only five black people came to my show. It had 300 targets. So, hey, I stick with what they like,” she adds jokingly.

Price believes Williams' message was visionary, even though it got him kicked out of Elektra Records in the 1970s. “He was saying incredible things, you know, socially and politically, and they dropped him,” he says. “And he never changed or compromised the artistic integrity of it. He kept it up all the time and has always been himself. “I strive to be like him.”

The social commentary of “Blackgrass” is of a softer variety, highlighted by “Songs to Sing,” a song originally written for his protégé Charlie Whitehead. Here it is transformed into a brilliant epic with echoes of Sam Cooke and the civil rights movement. There's also the newly written “Murder Ballad,” a chilling reinvention of an old folk song that's filled with racial tension and class violence. “We weren't thinking about killing anyone in particular. I don't think there are more than a couple of people I'd like to kill,” Williams muses, before quickly reciting the name of one of his former label bosses.

Indeed, Williams has a persistent obsession with success, money and status, a legacy perhaps of missed and denied opportunities. He boasts of owning nine cars at one point (“All of them are luxury except one,” she says) and a mansion on Long Island. Those things, he admits, are simply secondary. “For me, success is that people listen to it and like it. I did [the music] for me but where other people could enjoy it,” he says.

It's telling, then, that for the first time in his career, Williams decided to cede creative control of “Blackgrass” to his producer, Ryan Olson. It is their third album together and first since the 2020 country-soul collection “Sorry You Couldn't Make It.”

Jerry Williams Jr. sees “Blackgrass” as the beginning of a new era for Swamp Dogg. “This is me opening the door,” he says. “Now I want one without doors.”

(Sam Müller / for The Times)

“It's fantastic,” Olson says of working with Williams. “He's really confident. It's like there's no ego in it. He's just happy to bring new ideas into the mix. He's been doing it for so long. “If all relationships were like that, everything related to music would be a lot more fun.”

Olson also produced, directed and scored the documentary “Swamp Dogg Gets His Pool Painted,” which premiered at South by Southwest in March.

“He's family,” Olson says. “It's hard to get rid of family, you know?”

Olson and Price agree that Williams' close environment, including Clemons, helps keep him motivated, but Clemons also emphasizes his fierce inner drive.

“I think what keeps him fresh is that he believes in himself,” Clemons says. The particular purpose of this album increased that motivation. “This is something he really wants to push and spread, you know? He wants to leave things behind to help people. And music is healing.”

Beyond the personal story, “Blackgrass” is poignant for Williams because it will be released by Oh Boy Records, the label founded by his longtime friend, singer-songwriter John Prine, who died in 2020 from complications from COVID-19. The two had been close since working together on Elektra, with Prine's “Sam Stone” being a staple of Williams' live performances. Prine made some of his last recordings of “Sorry You Couldn't Make It.”

“That's another reason I feel successful: What record company is hiring an 81-year-old man?” Williams says, bursting into laughter.

But he sees “Blackgrass” only as the beginning of a new era for Swamp Dogg.

“I want to make a pure country album,” Williams says. “This is me opening the door. Now I want one without doors.”

He extends his hands in front of him, as if parting the seas.

“I hope to release at least five or six more albums before I leave,” he adds. “I already have the songs. I have to put melodies to some of them. And I have some ideas I want to write about.”