Even before “Slave Play” burst onto Broadway in 2019, producers and studios were already urging Jeremy O. Harris to adapt his play into a film or TV show.

“The first thing I thought,” says the 35-year-old playwright, “was absolutely not.”

“Slave Play,” which Harris wrote during her first year as a graduate student at Yale University, revolves around three modern interracial couples who engage in “antebellum sexual performance therapy” on a former Virginia plantation. , where disturbing topics such as racial trauma are addressed, slavery, sexual identity and power are explored. From its first incarnations at Yale, then off-Broadway at the New York Theater Workshop, and finally on Broadway, the play managed to shock, confuse, and provoke audiences.

As the play's reputation exploded, Harris remained adamant: “'Slave Play' is not a movie. It is a play”.

His close friend Chris Moukarbel, a documentary filmmaker and producer, urged him to film the tour of the play, telling Harris: “Jeremy, it's crazy that you didn't film any of this. This is crazy. This is a great moment for you.”

Harris objected.

“I'd just like to see some documentary about me or the play come out when I'm dead,” Harris says, laughing. “I was resistant to any kind of formalization of what it could be.”

However, here is the “Slave Game”. It's not a movie. A Play.”, an HBO original documentary directed by Harris that premiered this month at the Tribeca Festival and will begin streaming on Max on Thursday.

“Slave game. It's not a movie. A Play.”, like “Slave Play,” takes a deceptively simple premise (in this case, an inside look at how a production is put together) and turns that on its head, challenging viewers to reflect on their biases. and preconceived notions about culture and race.

The documentary focuses on a workshop that Harris convened in 2022 with acting students from the William Esper Studio in New York. For two intense days, he led the 23 students who played the eight characters in a reading and deconstruction of “Slave Play.” But the film is as much about Harris and his view of his world as it is about his work.

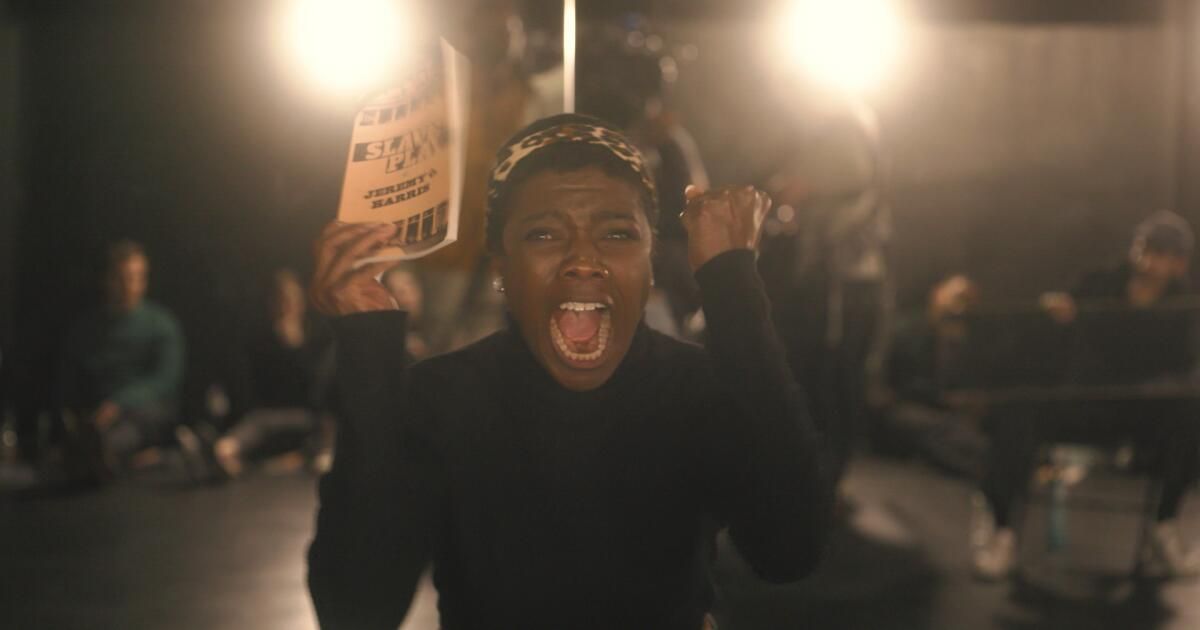

Jeremy O. Harris in the new documentary “Slave Play. It's not a movie. A play”, transmitted by Max.

(HBO)

“The initial idea was that I wanted to go back to Yale with the original Yale cast and recreate our original Yale workshop,” he says. “But now my friends from school are contract actors with real jobs.”

While the Yale cast members reunite in the documentary, it's not the way Harris originally envisioned. Still, the playwright-turned-first-time director wasn't afraid to plunge into uncharted territory. “It was a weird little experiment,” he says, “because everything I do is a weird little experiment. “I never push myself to work in any way other than like a playground.”

Harris already had an exclusive two-year deal with HBO, so his documentary seemed ideal for the cable network. Moukarbel, the film's producer, had also worked with HBO and shared his friend's passion for experimental work.

“The idea was: How do we make something that is experimental and also captures the challenging spirit of the work?” says Moukarbel. “For the viewer who did not see the play, he not only has a small window into the actual book of the play, but can also hear the lines read and performed.”

When “Slave Play” was ending its limited run in January 2020, Harris was offered the opportunity to move the production to a larger theater. At that point, he says, he considered filming that milestone. “Black plays are rarely performed on Broadway,” he says. “Now the small show that was able to return to a larger theater and last even longer. What would happen if we made a documentary about the transfer of the work?

Then COVID-19 happened. Broadway closed. The measure was postponed. But Harris remained committed to the project.

“What I decided to do was use it as a playground to make the kind of documentary I would like to see if I were a theater student,” he says. “If 'Slave Play' was a play I had read in class, it would be a great complement to that play.”

Even if you've never heard of Jeremy O. Harris, chances are you've seen him or his work.

The 6-foot-5 former Gucci model is also an actor (“Emily in Paris,” “Gossip Girl”), screenwriter (“Zola”) and producer (“Euphoria,” “Irma Vep”). In conversation, he is charming, playful, and witty, with an easy laugh that belies his thoughtful penchant for provocation. Think of him as that curious and cultured guest who makes sure his evening is memorable.

When “Slave Play” premiered at the Golden Theatre, Harris became the youngest black playwright to stage a play on Broadway, a distinction that has since been surpassed by “Ain't No Mo'” playwright Jordan E. Cooper. “That's the fun thing about having superlatives,” Harris says, helpfully. “You have them so someone else can take them.”

His self-confidence is evident in the film, but so is his honesty. For a brief but poignant moment, all of Harris' vulnerability is on display as he reacts to “Slave Play” receiving a record 12 Tony Award nominations but coming away empty-handed.

Harris astutely acknowledges the division of her labor at the top of the film with a video taken in a post-show conversation in 2019. In it, an angry white woman in the audience shouts, “I don't want to hear that white people are the damn thing.” plague… and a lot of stuff about how white people don't realize how racist they are.”

From the stage, Harris responds: “This play is about eight specific people, and if you don't see yourself here, that's great. … There are eight specific people who are in a play, which is a metaphor for our country. And a metaphor does not have to represent all the people that make it up.”

That wasn't the first time the play provoked an angry response. During the Off-Broadway run, an online campaign called for the production to be shut down due to its “graphic images mixed with laughter from a predominantly white audience.” There were even threats of violence, forcing the theater to beef up security.

“Slave Play” quickly became the talk of the town. She continued to make headlines when Rihanna, whose song “Work” appears in the play, attended a preview and angered some Broadway purists by texting during the show. It turned out that she was texting the playwright, who fiercely defended her.

“One thing I said then and still stand by is that theater has to deal with the fact that phones are a fact, and controlling people about using their phones in the theater is impossible,” Harris says. “We have integrated these objects into our lives as if they were new appendages, and not recognizing how much they reconfigured the ways we interact with space, the way we interact with art, is another barrier we have to break down in order to build new audiences. ”.

Harris remains committed to changing the norms of theater to attract diverse and younger audiences. To that end, he and his producers reserved 10,000 $39 tickets during the Broadway run of “Slave Play.”

“I didn't see my first Broadway show until I was 20, because I couldn't afford it,” he says. “I'm trying to break down as many barriers to entry as possible for the kid who wants to engage with theater on a broader level, and also make theater sexy and cool and different.”

Playwright Jeremy O. Harris, dressed in pink, is surrounded by acting students in a scene from the new documentary “Slave Play. It's not a movie. A play”, transmitted by Max.

(HBO)

One of the beneficiaries of the discounted tickets was actor Amani Owusu, 28, who would later participate in the workshop, playing Kaneisha, a sexually frustrated black woman who finds release in playing a submissive slave to her partner's whip. white, “Massa Jim”, in the The surprising first act of the play.

“Everyone was talking about 'Slave Play,' but no one was giving any kind of synopsis; everyone was saying, 'Go watch it,'” Owusu recalls. “We were very shocked by the first half. We thought, 'Should we stay? Should we go?'”

Things that didn't make sense when he saw the play came to light during the workshop after hearing Harris' motivations behind the writing. “It seemed like two intense, separate experiences,” he says. “Seeing the play and saying, 'Wow, this is the craziest thing I've ever seen in my life,' then revisiting it and things really click.”

LaTonya Grant, 45, who also played Kaneisha in the workshop, says she avoided “Slave Play” on Broadway. “Hearing about slavery and race relations and all the pain that comes around that topic, she had no interest in seeing it,” she says. And when she was chosen for the workshop, she initially didn't want to participate. “But after reading the play, I said, 'Oh, wow, this isn't what she thought at all. Count me in,'” she says. “I had to get comfortable sitting in the midst of discomfort.”

To this day, Harris remains surprised by the success of “Slave Play,” but also encouraged by the impact it has had on theater.

“I didn't think at all that there was something bigger to this work outside of a kind of niche notoriety,” he says. “In the wake of 'Slave Play' doing so well, there was a huge push and sort of resurgence of work by queer people, work by people of color, women. “People were beginning to see that there was the possibility of celebrating diverse works in commercial settings.”

Beginning in 2025, Harris will serve as the inaugural creative director of Williamstown Theater Festival's Creative Collective and is juggling other projects, including a new production company. Meanwhile, Harris returns to London this week to work on “Slave Play,” starring Kit Harrington (“Game of Thrones”) and Olivia Washington, daughter of Denzel and Pauletta Washington. The performances, which begin June 29, will include two “Black Out” nights similar to Broadway performances for audiences who identify as Black.

“To have an all-black audience at the possibility that maybe we could have a space where a black play could come to Broadway and be as full of black people as a Tyler Perry play was phenomenal,” he says. “We all have to make our voices heard. That's one of the reasons I started producing: I complain about it, I could fight it or I could become an agent of change and start working to make the things I want to happen happen.”