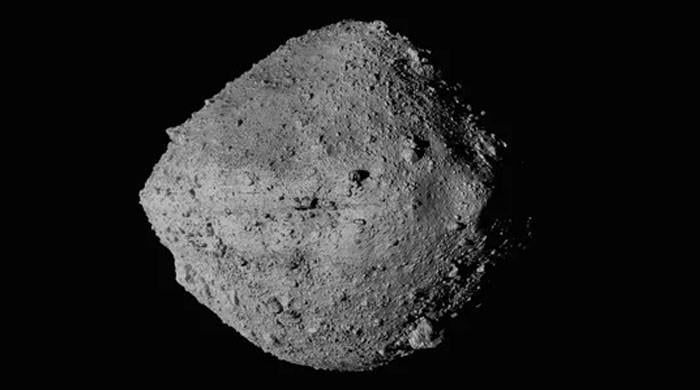

WASHINGTON: A heated debate over the cosmic rock that killed the dinosaurs has gripped scientists for decades, but a new study has revealed some important — and bizarre — insights into the impactor's origin story.

The researchers, whose findings were published Thursday in the journal Science, used a groundbreaking technique to show that the apocalyptic culprit that crashed into Earth's surface 66 million years ago, causing the most recent mass extinction, had formed beyond the orbit of Jupiter.

They also refute the idea that it was a comet.

New insights into the apparent asteroid that crashed in Chicxulub, in what is now Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, could improve understanding of celestial objects that have impacted our planet.

“We can now, with all this knowledge… say that this asteroid initially formed beyond Jupiter,” said Mario Fischer-Godde, lead author of the study and a geochemist at the University of Cologne. AFP.

The findings are particularly noteworthy given how infrequently this type of asteroid hits Earth.

That information could be useful in assessing future threats or determining how water came to be on this planet, Fischer-Godde said.

Samples

The new findings are based on the analysis of sediment samples formed during the period between the Cretaceous and Paleogene eras, the time of the cataclysmic asteroid impact.

The researchers measured isotopes of the element ruthenium, which is not uncommon in asteroids but is extremely rare on Earth. So by inspecting deposits in multiple geological layers that mark the impact debris at Chicxulub, they were able to be confident that the ruthenium they studied came “100 percent from this asteroid.”

“Our laboratory in Cologne is one of the few laboratories that can perform these measurements,” and it was the first time such study techniques had been used on layers of impact debris, Fischer-Godde said.

Ruthenium isotopes can be used to distinguish between two main groups of asteroids: C-type, or carbonaceous, asteroids that formed in the outer solar system, and S-type, silicate asteroids from the inner solar system closer to the Sun.

The study claims that the asteroid that triggered a megathrust earthquake, precipitated a global winter and wiped out the dinosaurs and most other life was a C-type asteroid that formed beyond Jupiter.

Studies from two decades ago had already made such an assumption, but with much less certainty.

The findings are surprising because most meteorites (fragments of asteroids that fall to Earth) are S-type, Fischer-Godde said.

Does this mean that the Chicxulub impactor formed beyond Jupiter and headed straight for our planet? Not necessarily.

“We can't really be sure where the asteroid was hiding just before it hit Earth,” Fischer-Godde said, adding that after its formation, it may have made a stopover in the asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter and where most meteorites originate.

It's not a comet

The study also rules out the idea that the object that caused the impact was a comet, an amalgamation of icy rocks from the very edge of the solar system. This hypothesis was put forward in a highly publicised study in 2021, based on statistical simulations.

Sample analyses show that the celestial object had a very different composition than a subset of meteorites thought to have been comets in the past. It is therefore “unlikely” that the impacting object in question was a comet, Fischer-Godde said.

As for the broader utility of his findings, the geochemist offered two suggestions.

He believes that defining more precisely the nature of the asteroids that have struck the Earth since its beginnings some 4.5 billion years ago could help solve the enigma of the origin of our planet's water.

Scientists believe the water may have been brought to Earth by asteroids, probably C-type asteroids like the one that struck 66 million years ago, although they are less common.

Studying asteroids from the past also allows humanity to prepare for the future, Fischer-Godde said.

“If we find that past mass extinction events could also be linked to C-type asteroid impacts, then… if there's ever going to be a C-type asteroid in an Earth-crossing orbit, we have to be very careful,” he said, “because it could be the last one we ever witness.”