In a sense, the atomic scare films of decades past are the children of J. Robert Oppenheimer and the parents of the film “Oppenheimer.”

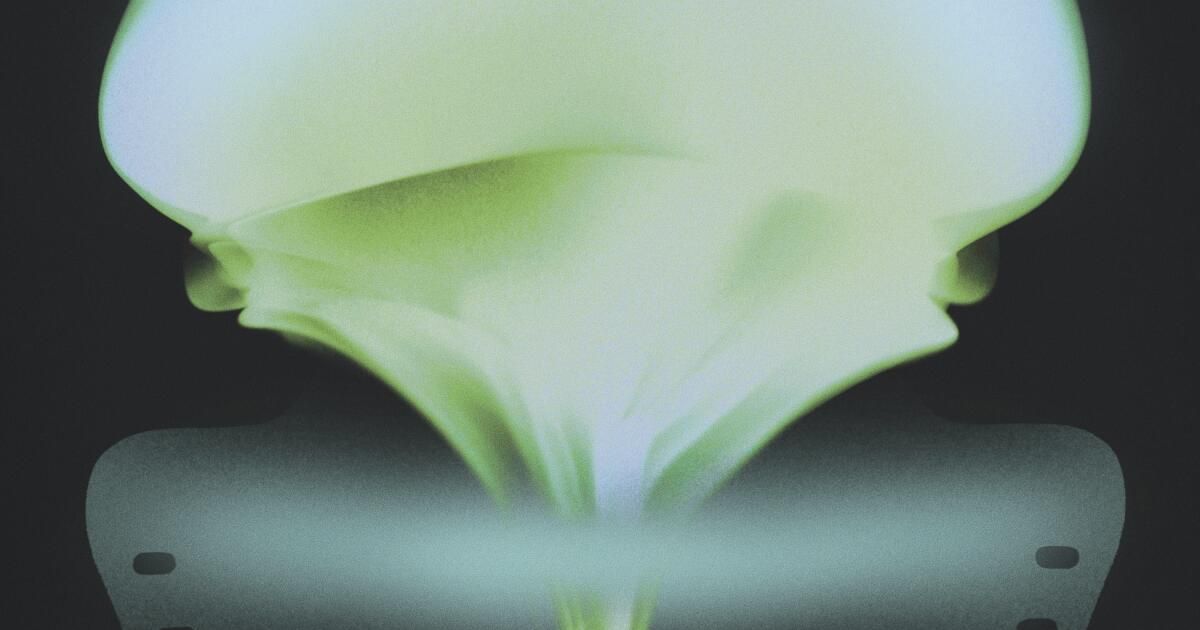

(Illustration by Agnes Jonas / for The Times)

The award juggernaut “Oppenheimer” is the story not only of one man, J. Robert Oppenheimer, but also of the world he helped create, a world in which fear of the atomic bomb, and then the hydrogen bomb , became a regular feature of American life. life. Oppenheimer, played by Cillian Murphy, saw the terror coming and experienced his fair share of remorse; Some of the film's most indelible scenes show the Los Alamos boss shaking his head at what he has accomplished.

Meanwhile, the movies also saw the capacity for atomic terrorism, beginning in the 1950s, moving through the 1960s, and reaching an era of renewed anxiety in the Reagan-era weapons buildup. These films spanned science fiction, drama, film noir, and even comedy, while highlighting a brave new world marked by duck-and-cover drills, apocalyptic speculation, and the legitimate possibility that the world could end at any moment, thanks in large part to man who, based on the Bhagavad Gita, supposedly described himself as “Death, destroyer of worlds.”

The first wave of atomic films was science fiction, a genre that, as film historian Foster Hirsch points out, did not even exist as a genre in the United States until the 1950s. “When Hollywood addressed the atomic age, it did not do so in a in a direct and realistic way, but in a fantastical, allegorical and metaphorical way and often through monsters,” said Hirsch, author of “Hollywood and the Movies of the Fifties. in a recent video interview. “That's how Hollywood was able to dramatize the impact of the bomb and the fact that we had the power to blow ourselves up.” Hirsch points to the murderous arctic creature in “The Thing from Another World” (1951), the rampaging dinosaur awakened by atomic testing in “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms” (1953), and the giant ants that swarm the New Mexico desert in “They! ” (1954).

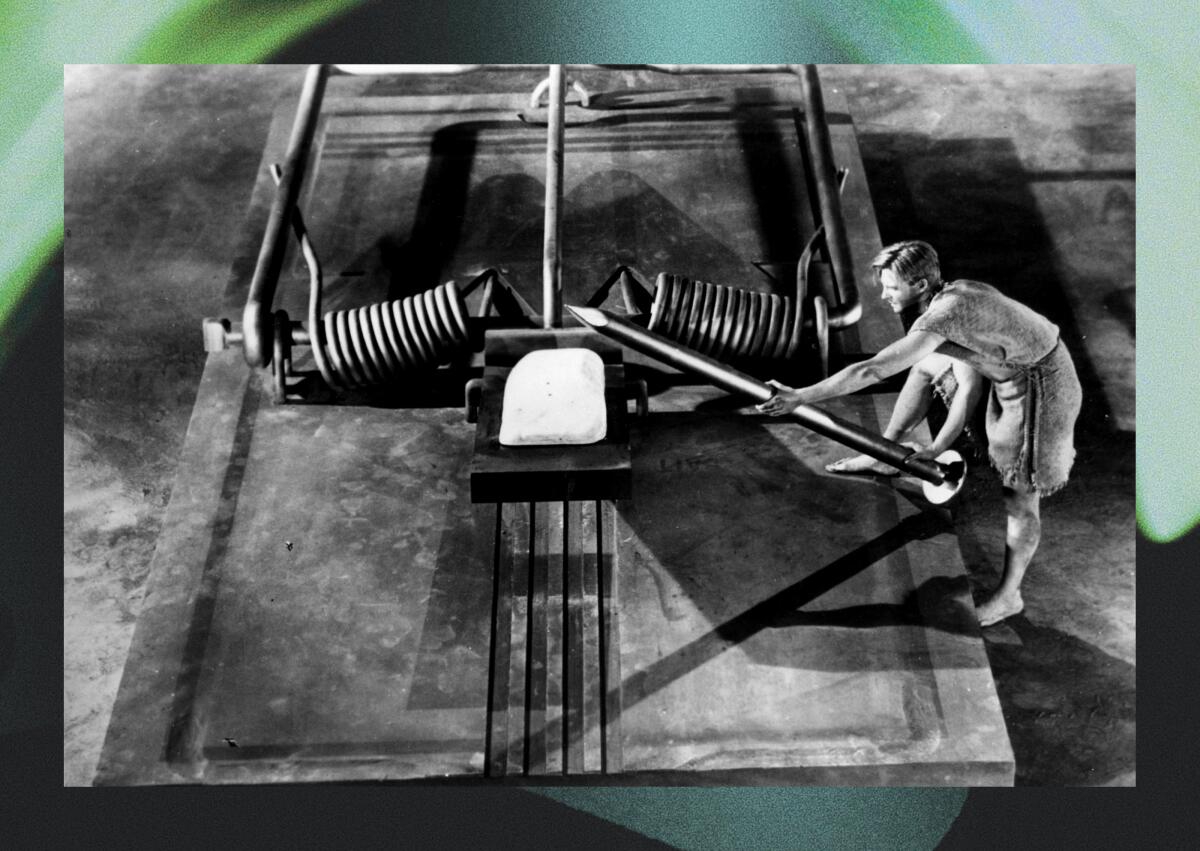

“The Incredible Shrinking Man” (1957) is a metaphor-laden fantasy in which a businessman (Grant Williams) is reduced to almost microscopic size after being exposed to a cloud of radiation and insecticide.

Among Hirsch's favorite films of the period was Jack Arnold's “The Incredible Shrinking Man” (1957), a metaphor-laden fantasy in which a businessman (Grant Williams) is reduced to an almost microscopic size. after exposing it to a cloud of radiation and insecticide. “We are reduced to zero as if we were reborn in another world,” Hirsch says. “It is the end of this world and the beginning of another parallel universe that we cannot yet enter.”

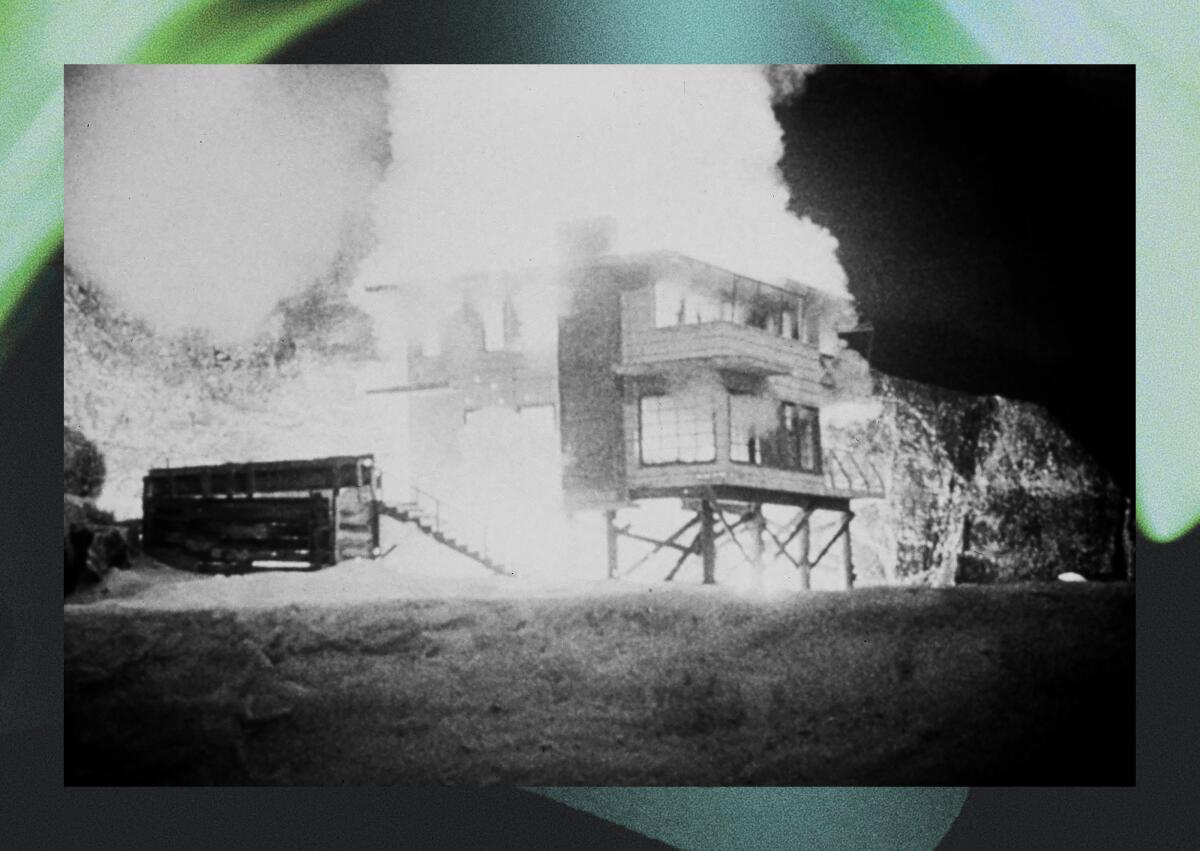

But science fiction wasn't the only genre concerned with the bomb in the '50s. The same decade brought Robert Aldrich's “Kiss Me Deadly” (1955), a deeply cynical noir starring Ralph Meeker as the sleazy private detective Mike Hammer by pulp novelist Mickey Spillane. Hammer is on the trail of “the big what,” a highly coveted case that everyone seems willing to kill for. Hammer believes there is some kind of treasure inside. He has no idea. A police lieutenant tries to explain what is at stake: “I'm going to say a few words. They are just harmless words. Just a bunch of letters mixed up. But its meaning is very important. He tries to understand what they mean: Manhattan Project. Poplars. Trinity.” He sounds like he just came back from watching “Oppenheimer.” But he's trying to warn Hammer about the case, which is actually Pandora's Box. And when it opens, at the film's climax, it leaves a powerful cloud .

Atomic concerns were addressed in noir style with Mickey Spillane's Detective Mike Hammer in 1955's “Kiss Me Deadly.”

Anxiety increased in the 1960s. The Cuban missile crisis of 1962 made the threat of imminent nuclear war more real than ever. And the movies were there to respond, first as comedy and then as tragedy. 1964 brought both “Dr. Strangelove” and “Fail Safe,” which used the same basic premise (a systemic failure leads to nuclear war between the United States and Russia) to produce drastically disparate films.

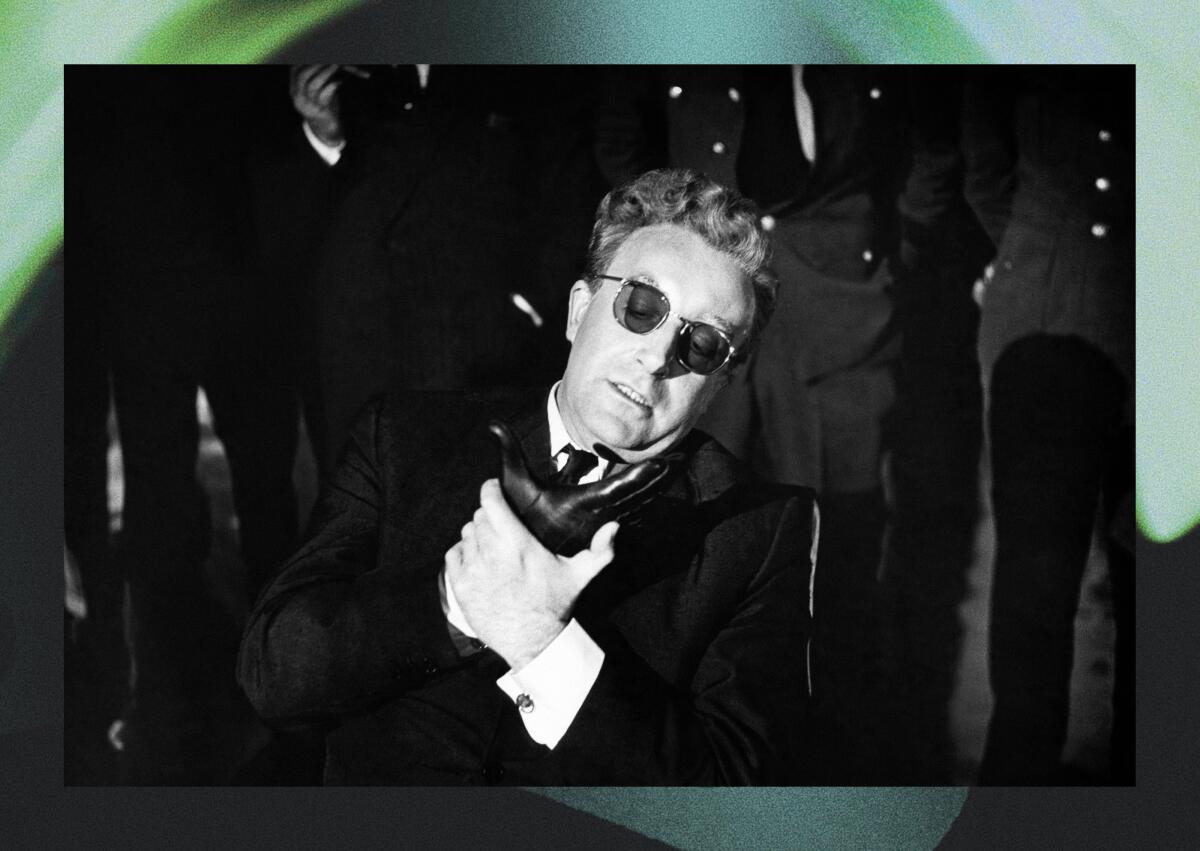

Stanley Kubrick’s “Strangelove” features a psychotic, gung-ho general, Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden), who orders an attack on Russia fearing a communist plot to drain its “precious bodily fluids.” The black comedy that follows encompasses the jolly General Buck Turgidson (played by George C. Scott and modeled after the head of the US Strategic Air Command, Curtis LeMay); ineffective US President Merkin Muffley (Peter Sellers), the spitting image of two-time Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson; and Dr. Strangelove himself (also Sellers), an American military advisor and holdover from the Third Reich excited at the prospect of mutual destruction.

The nuclear war between the United States and Russia was a priority for filmmakers, as was the case with Stanley Kubrick's 1964 film “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb”, starring Peter Sellers.

The most melancholic version came at the end of the year. In Sidney Lumet's underrated “Fail Safe,” a computer glitch sends American bombers toward Russia. The stoic president (Henry Fonda) negotiates with his Soviet counterpart as the clock ticks; The two men eventually reach a horrible but somehow reasonable compromise that essentially trades the destruction of Moscow for the destruction of New York City. If “Strangelove” was a laugh, “Fail Safe” was a gasp. But that year there was another key piece of atomic cinema, this one a strategic attack: the “Daisy” Lyndon B. Johnson presidential campaign ad, which used an innocent girl, a flower, a countdown, and a climactic mushroom cloud. to suggest that Johnson's opponent, Barry Goldwater, would lead the world to Armageddon. Political advertising would never be civilized again.

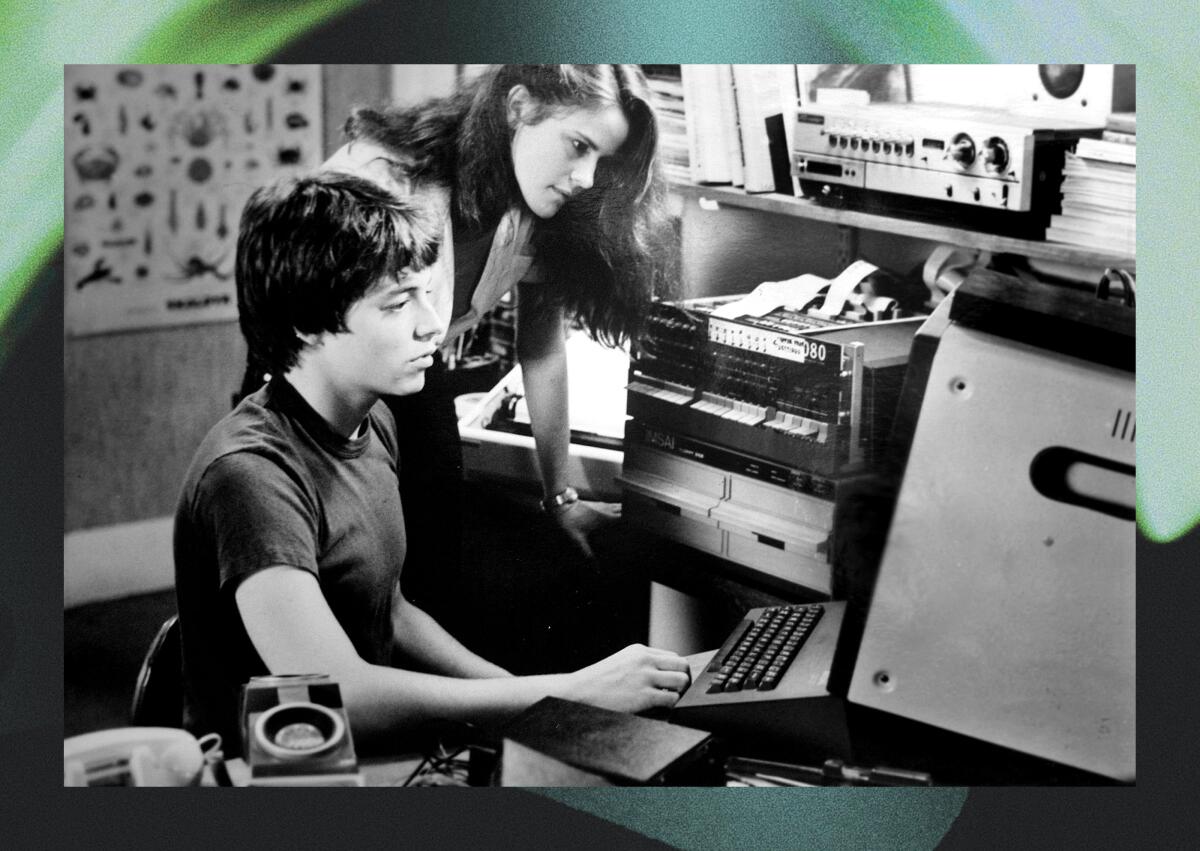

The 1980s brought a new era of nuclear fear, when the United States, under President Ronald Reagan, engaged Russia in a renewed arms race. Like 1964, 1983 proved to be an eventful year for atomic cinema. More than 100 million people tuned in to Nicholas Meyer's “The Day After,” a television movie that dramatized the effects of the nuclear holocaust in Kansas. Meanwhile, in John Badham's “War Games,” a mischievous teenager (Matthew Broderick) accidentally hacks into the American missile system, bringing the country once again to the brink of mass destruction.

Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy star in 1983's “War Games,” even as the '80s ushered in a new arms race with Russia.

This is the era that inspired journalist James Oliphant's obsession with atomic films, an obsession that would lead him to create his Substack Nuclear Theatre. Reflecting on films about the nuclear threat and broader issues of the Cold War, Oliphant taps into his years as a 1980s high school student who couldn't learn to stop worrying and love the bomb.

“There was a feeling that there was no way out,” he said in a video interview. “I couldn't even imagine that there would be any kind of disarmament or that any of the sides would back down. Of course, little could he have imagined that the Soviet Union would collapse in a matter of years and that the threat would seemingly disappear.”

But it never completely disappears. In a sense, all of these films are children of Oppenheimer and parents of “Oppenheimer.” That Trinity test explosion, so hauntingly depicted in the film, still resonates. And the technology he spearheaded is still more than capable of destroying worlds.