“It's been a hell of a ride.”

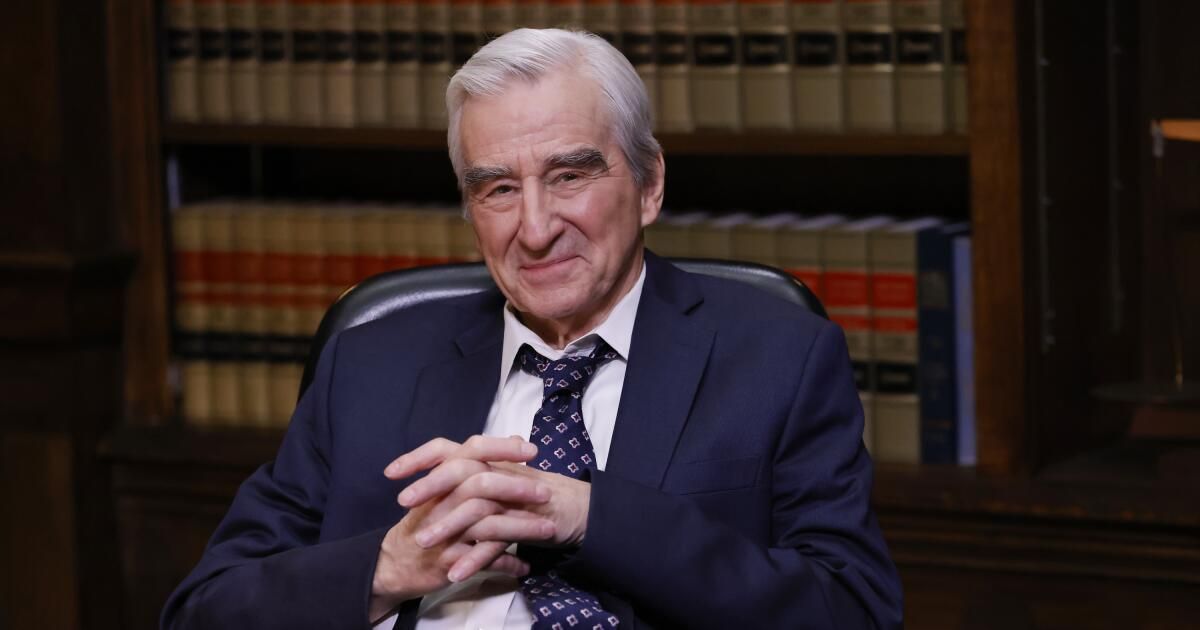

With those parting words, Jack McCoy stepped down from his job as Manhattan district attorney after decades of public service — and Sam Waterston bid farewell to his signature role on “Law & Order” after 19 seasons and 405 episodes spread over 30 years.

To put this run into perspective, Waterston made his debut appearance as McCoy in September 1994 in the Season 5 premiere of “Law & Order” — the same week that “ER” and “Friends” premiered on NBC. The Dick Wolf procedural — which famously told stories about “the police who investigate crimes and the district attorneys who prosecute the offenders” was already a well-established hit, but it had yet to become a ubiquitous, seemingly indestructible pop culture franchise.

Waterston, who joined the series after the contentious departure of actor Michael Moriarty, helped prove that the format was durable enough to withstand major cast shakeups. Yet he also became the closest thing “Law & Order” had to a central protagonist — the “ultimate conscience of the show,” as Wolf has put it.

Well before male antiheroes took over TV, Waterston played McCoy as a no-nonsense attorney who was passionate about justice but also willing to bend the rules in order to obtain a conviction — a prickly character whose sharp edges were somehow softened by Waterston's soothing voice and avuncular demeanor. And although McCoy's personal life was hinted at only fleetingly throughout the series, the character clearly wrestled with private demons (including a proclivity for affairs with his glamorous assistant district attorneys).

A Yale-educated actor who has played Hamlet on Broadway, Waterston admits there was a time he looked down on TV. Initially, he only planned to do a single season of “Law & Order.” But Waterston remained on the series until it was canceled in 2010. He is the rare actor to star in a long-running TV series who managed not to be pigeonholed by the part that made him famous, working continually in the dozen years “Law & Order” was off the air in shows including “Grace and Frankie.” He has agreed to reprise his role when NBC revived the series in 2022, anchoring a new cast that included Hugh Dancy as assistant district attorney Nolan Price. But earlier this month, NBC announced that Waterston would be leaving the series, with Tony Goldwyn set to star as the incoming DA

Waterston's farewell episode — written by Rick Eid and Pamela Wechsler and fittingly titled “Last Dance” — follows the case of Scott Kelton (Rob Benedict), a billionaire tech mogul who is accused of murdering a young woman in Central Park. Major Robert Payne (Bruce Altman), whose son is involved in the case, pushes the DA's office to cut a deal with Kelton — or else he'll support McCoy's opponent in the coming election. McCoy resists the pressure and decides to try the case himself, urging the jury to rule fairly and without prejudice despite the high-profile defendant. It works: Kelton is convicted. Over a celebratory drink with Price, he announces he's going to retire so that the governor can appoint “someone with integrity” to the job. In the closing shot of the episode, McCoy stands alone at night outside the Supreme Court building in Lower Manhattan — then walks off into the darkness.

The Times recently spoke via Zoom with Waterston, who will play Franklin Roosevelt in Tyler Perry's upcoming World War II drama “Six Triple Eight.” At 83, he is eager to tread the boards once again — and to continue working as steadily as he has for the last six decades.

“Actors don't really get to tell the future,” he said. “But I'm open for business. If anybody's reading this and thinking, 'Oh, too bad. I have retired.' “I haven't retired.”

Jill Hennessy, left, and Sam Waterston in a 1995 episode of “Law & Order.”

(Jessica Burnstein/NBC)

Let's start with the obvious: Why did you decided to leave now?

I always knew that I was going to stay on a short time. I didn't want to turn on the TV and see someone else playing the part when the show came back [in 2022] but I knew it was not for the long term. This was always going to be the year [to leave]. And then “Law & Order” designed just a beautiful exit. I couldn't have been more pleased with it. They gave me this fantastic send-off, with a pop-up delicatessen on the set, called Sam's Delicatessen. The last shots were all in the courtroom and speeches were made. Dick Wolf showed up. It was something else.

What did you make of McCoy's decision to step down rather than face likely defeat in an election?

Once I found out that Sam Waterston was leaving, it was pretty much a done deal.

Take me back to 1994, when you were cast on the show. What made the role appealing to you?

Dick Wolf took me out to lunch and persuaded me that it was a really good idea. Ed Sherin was the executive producer in New York, and he set the tone and made it a really interesting place to work. He was a theater director, and he did a lot of work in television. He had the dream of a lifetime to set up a resident theater somewhere, but he said that this was the fulfillment of that dream. And he grew talent, staff, sound guys, focus pullers — people who are now directors out in the world because of him. It was an extraordinary place to be. It was easy to stay, but I always thought I was going to leave the next year. I kept on signing up for one more season.

It was known for drawing many actors from New York theater.

We used to joke that it was the Café de la Paix of television. You know that saying about the Café de la Paix, “If you sit there long enough, the whole world passes by?” We used to joke, that was what went on [at “Law & Order”]. We had fantastic guest stars, and all kinds of people who then grew up to be stars on their own. Don't ask me to name them.

One of the things that's interesting about “Law & Order” is that we never learn much about the characters outside of work. Jack McCoy's backstory is pretty patchy, even after 19 seasons. Does this present any challenges — or rewards — to you as a performer?

The reward is that your own life is not used up. A lot of what you can do and what you are as an actor is also not used up. That means that if someone goes to see you in a play or a movie while you're doing “Law & Order,” the audience doesn't think, “Oh, gee, I already saw this.” And the stuff that you do get to do on the show, and in the case of [when I was] playing McCoy, was very intense, very engaging. The quality control at Wolf Films is fantastically high, so it was good stuff.

Do you have a favorite scene or episode from your run on the series?

The episode that hit me the hardest didn't really have to do with me, it had to do with Steven Hill, who was playing the DA [Adam Schiff] in those days. We gave a death penalty [storyline in which] his wife was on life support and dying. He was against pursuing the death penalty [in a case]but the state of New York was for it. [In the episode, “Terminal,”] they juxtaposed the execution, which Jack and his assistant witnessed, with Steven Hill sitting at his wife's bedside as she was taken off life support. It was unforgettable. It wasn't just great “Law & Order,” it was great TV and not just great TV, but really, really mighty.

How do you think Jack McCoy evolved over the years? Especially in earlier seasons, he was known for doing whatever it took to get a conviction. Did he mellow with age?

I don't think I have changed. I think being the DA was hard on him because he didn't change, but to do what was necessary to do the job, he had to restrain himself in ways that he didn't have to before.

You came back to the show after 12 years away. Was that strange?

What was strange was how familiar it was. que was really strange was that our set, for the whole time that I was on the show, had been at Chelsea Piers, on the west side of Manhattan and they rebuilt those sets at a studio in Queens. You walked onto the set and you're back in the same world. It made the hair stand up on the back of your neck. When I did “The Great Gatsby,” I walked out of a door in Newport, RI, and walked into a room in London. That was creepy too.

You did plenty of TV before “Law & Order,” including the NBC drama “I'll Fly Away,” but you were primarily known for movies and theater. Did you watch down on TV at the time?

Of course I did. We all had the same prejudices and now, what and behold, streaming services are the business. We looked down on it, and we were stupid. When I was growing up, theater was the thing. And the movies were looked down upon. How unbelievable is that? We were dumb people.

You have played Abraham Lincoln on numerous occasions (including in the miniseries “Lincoln” and as a voice actor in Ken Burns' “The Civil War”), What keeps drawing you back to this part?

I always used to say that if you're an actor, there should be some reward for being plain. I counted that as the reward. [laughs] It was an excuse to go down an endless rabbit hole of fascination with a really extraordinary person. You can't exhaust the fascination, especially if you like words. I started out wanting to be a Shakespearean actor. That's all I wanted. And Lincoln had a way with words.

Odelya Halevi, left, as Samantha Maroun, Hugh Dancy as Nolan Price and Sam Waterston in a scene from “Law & Order.”

(Eric Liebowitz/NBC)

I have to point out that you also played Robert Oppenheimer in a 1980 TV series called “Oppenheimer.”

If you live long enough, all the parts you've ever played in your life will come back to you being played by someone else.

As you look ahead at your career, are there roles that you are still hoping to play?

Sure, but there is no planning. Bradley Cooper plans his career. I am not an actor-producer, so I am very much subject to what comes under the door. There are lots of things I want to do. Joel Gray and I want to do “On Borrowed Time,” a play that was made in 1938 and made into a movie starring Lionel Barrymore. I want to do that, but will I get to do it? We'll see.

How have you been spending the spare time since you finished the show?

It is mind-boggling. There's never been a time in all the 60 years of my working as an actor — for which I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the people reading this article, and everyone else in the world [who is] watching — there's really been no time when I wasn't either working, or really sweating looking for work. This is the first time I've walked off a set without thinking, “What the hell am I going to do next?” It was literally a physical feeling that there was a space opening up in my head that I had not even known existed for all those years, space that was taken up by the job or the search for the job. Suddenly you're free to think about all kinds of other things. It's intoxicating and makes you feel drunk.

Fascinating. Is it the freedom of not having to learn all those lines?

That's part of it. “I have these lines, will I know them on the day?” Also, for an actor, it's got to do with having a piece of your mind occupied by someone other than yourself — by the character. I haven't retired, but McCoy has. I don't know where he is. He's on a beach in Brazil or something. But he's not in my head and it's really quite extraordinary and wonderful. Just wonderful! But I loved [playing McCoy]. Boy, what a blessing.

You and Jerry Orbach They were named living landmarks in New York City. Do you have any recollections of working with him, even though you were not often in scenes together?

We weren't in that many scenes. But we did pass each other in the hall in the studio very often. And he's one of the most extraordinary and beautiful people I have ever known, certainly in the profession. I broke one of his rules, which was that you never leave a show while it's running. I'm going around, saying this to anyone who will listen, that I hope that the theater gods won't punish me for breaking his rules.

Do you ever find yourself in a hotel room or on a plane, watching yourself in old episodes of “Law & Order” and getting sucked in?

My wife likes to watch old episodes of “Law & Order” while she's cooking. Sometimes I'm passing through the kitchen and I stop and I think, “Why were you so critical of how you looked in those days? Look at yourself now.”