I began the speech on “Fellow Travellers,” my adaptation of Thomas Mallon’s beautiful novel, with a fragment of my personal story. Growing up in a small town in Pennsylvania in the 1960s, I never heard the word “homosexual” out loud. There were no gay characters in movies, books or television. I grew up believing that my hidden self was evil. Unspeakable.

I was captivated by Mallon's story about Hawkins (Hawk) Fuller and Timothy Laughlin, two very different men who were having a passionate affair in 1950s Washington, DC, during the government's crusade against homosexuals. Hawk is selfish and trusting. Tim is religious and sensitive. They struggle to love while hiding the part of themselves that allows them to love.

I was told that this story would be impossible to sell for three reasons: it was period, political, and gay.

Being rebellious by nature, I decided to lean into elements of the story that were considered challenging. Is a period piece problematic? In our scripts, every detail will be meticulously researched and much of the dialogue will come from historical records.

Instead of avoiding politics, we will turn our political characters into flesh-and-blood antagonists, illuminating the dark secrets behind their destructive acts. Is this all too gay? We will create a gay love story with passionate, tense and hard sex scenes. We'll take you on a tour of gay sex through the decades, from park bathrooms to backroom bars. In the end, we will break your heart.

We sold the show and we did it. I have to give credit to the executives at Fremantle and Showtime who took our “cheeky” approach (the expression seems apt) and to my intrepid executive producers: Robbie Rogers, Dan Minahan and Matt Bomer.

We knew we needed to wrap our challenging elements within a story that was universal and modern. The paranoia of the McCarthy era seemed remote, and Mallon's book ends in 1957. But I had lived through the early days of AIDS, known terror as those around me fell ill and died, and witnessed hate directed at my community.

I realized that the AIDS crisis could serve as a culmination of the fear of lavender. Tim would live in San Francisco, as an activist, in the early days of the epidemic. Hawk will journey to Tim seeking forgiveness, giving Tim power over Hawk in a reversal of his previous roles. And these timelines will alternate throughout the show.

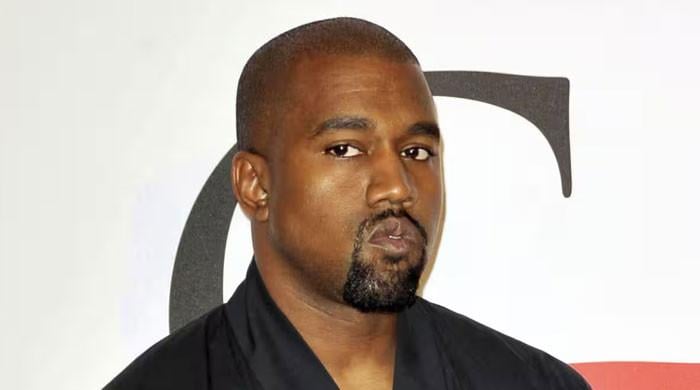

Ron Nyswaner created a gay love story, starring Jonathan Bailey, left, and Matt Bomer, “with passionate, tense and rough sex scenes.”

(Show time)

But the wheels of my mind kept turning. How could I get Hawk and Tim together once or twice more? Again I turned to personal history.

In high school, I was known as the sissy girl with liberal politics who loved Jesus. I protested the Vietnam War and refused to take the Pledge of Allegiance because the United States had not yet achieved “liberty and justice for all.” When I was relegated to the back row of desks in my classroom, I considered it a badge of honor.

The sixth episode of the series, “Beyond Measure”, is set in 1968. Tim's passionate anti-communist politics have transformed into pacifist politics. His Christianity, like mine in my youth, addresses his need to be exalted, to live and love “without measure.” As a teenager, my religious fervor offered what my peers found in sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll.

I came out in the late 1970s, drinking, snorting, and falling into bed with sweaty strangers after nights of dancing with Donna, Thelma, and Grace. It was glorious. We had some gay heroes, but none more inspiring than Harvey Milk, the first nationally prominent gay politician. His murder was a shock and a wake-up call, reminding us that we had only just begun to gain our freedom.

“Fellow Travelers” episode 7, “White Nights,” is set in 1979. Hawk and Tim reunite on Fire Island. They splash in the ocean, visit the meat rack and sweat on the dance floor. They seem free, until Hawk is forced to face unbearable pain. We set our second set of lovers, Marcus and Frankie, in San Francisco, for the “explosion of gay rage” that followed the trial of Harvey Milk's killer, Dan White, and his obscenely lenient sentencing.

Hawk's pain and longing to lose himself in drugs and sex were influenced by my own descent into alcoholism and addiction. The candlelight march in honor of Milk that ends the episode is combined with Hawk's decision to return home. Twenty-five years ago, I began my own journey home, finding a way to live sober.

The series ends on the National Mall in 1987 with the first exhibit of AIDS Quilt. Hawk kneels before Tim's comforter and puts into words the truth he has carried in his heart for three and a half decades: “He was the man he loved.” Hawk finds redemption by saying the unspeakable.

I know how he feels.