What is more psychically exhausting, in fiction and I suppose in life, than the story of the double agent, the mole, the traitor embedded among those he works against? It's a dramatic theme we return to again and again: Keri Russell and Matthew Rhys got six seasons of “The Americans” a few years ago. But as a viewer (and maybe it's just me), whenever the characters go undercover, I want them to get along with the people they're spying on, even like them, and I'm always disappointed, even annoyed, when Their cover has been blown, not to the spies, but to the people whose trust they betrayed. It's hard for me, I can tell you that.

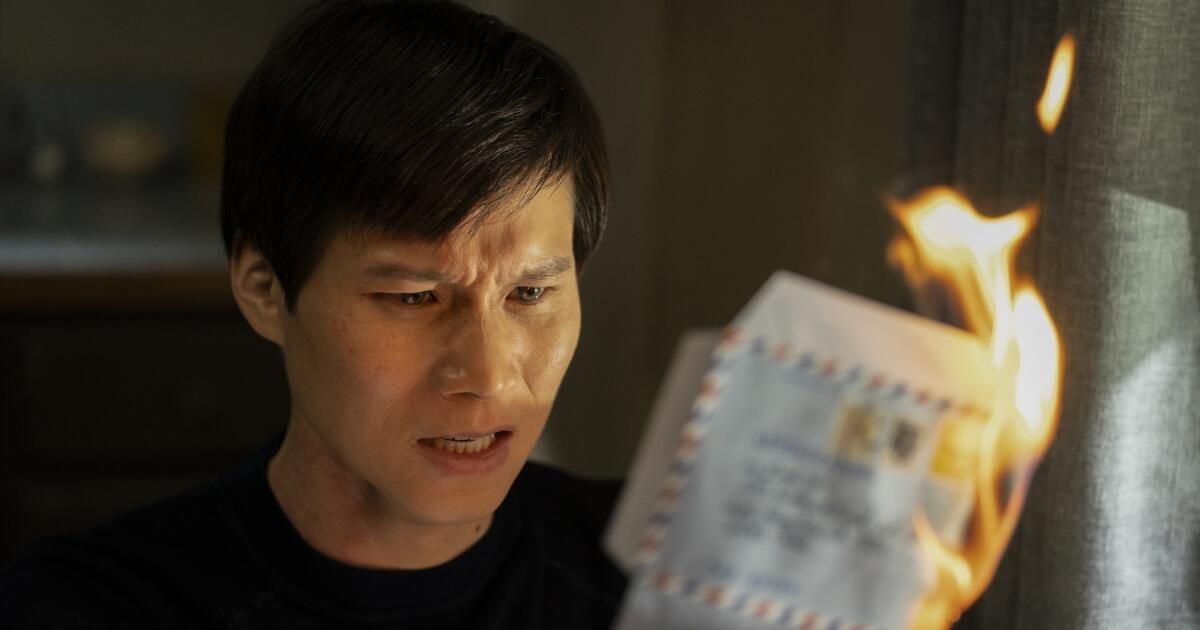

This added tension animates “The Sympathizer,” a serious dark comedy premiering Sunday at 9 p.m. Pacific on HBO. (It's no less tense for being a comedy.) Adapted by Park Chan-wook, who also directs the first three episodes, and Don McKellar from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Viet Thanh Nguyen, and set immediately after the Vietnam War. The American War, as they called it in Vietnam, is the portrait of a divided people and a divided person. The main character, called only the Captain (Hoa Xuande), is a “sympathizer” in both the American construction of “communist sympathizer” and someone who can see both sides of a story, not necessarily the best quality, psychologically speaking, for a spy.

When we meet him, on the eve of the terrifyingly recreated fall of Saigon, the Captain is a North Vietnamese mole working for the South Vietnamese secret police, under the command of the general (Toan Le), in whose house he lives with his wife. of the general. , Madame (Nguyen Cao Ky Duyen) and her daughter, Lana (Vy Le), an aspiring singer who in her head already lives in the United States. Much to his chagrin, he is ordered to travel to the United States to continue monitoring the General, whose paranoia he must alleviate and whose development plans he appears to support. Their war continues.

The Captain has a split personality in other ways. He attended college in the United States, speaks English fluently, and likes funk and soul music. He is biracial, the illegitimate son of a Vietnamese mother (deceased) and a French father, who remains in the shadows until almost the end of the series. As a child they called him “mestizo” and beat him. (“You're not half of anything,” says his mother. “You're double of everything.”) As an adult, they call him a bastard.

From left to right, Man (Duy Nguyen), Bon (Fred Nguyen Khan) and the Captain (Hoa Xuande), the friends who form the core of “The Sympathizer.”

(Hopper Stone/HBO)

However, he makes two childhood friends, together they call themselves the Three Musketeers: Man (Duy Nguyễn), who will also end up working undercover for the Viet Cong, and Bon (Fred Nguyen Khan), who has no idea who his friends are. friends. up and will carry a heavy load of trauma in his American second act. More than anything, it's their relationships that drive the series, which, for all its many themes and observations, turns out to be, most poignantly, a story of friendship.

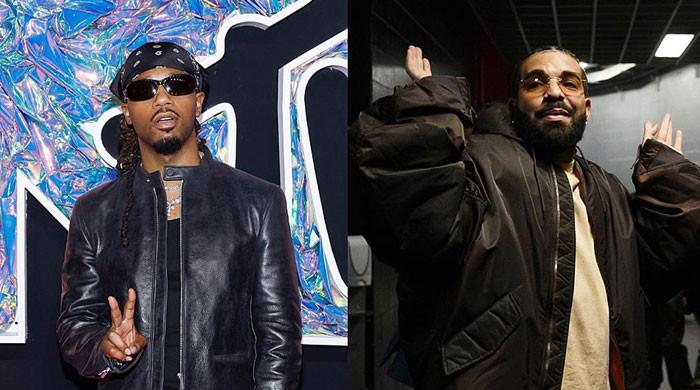

As a sort of counterpart to the Captain's mental split, Robert Downey Jr. plays four characters who could be seen as one, in that they are all aspects of American self-importance. These are the most comical figures in the series: caricatures, but interpreted with commitment. We will see them gathered at the same table in a scene, set in “the natural habitat of the most dangerous creature on earth, the white man in a suit and tie: the rotisserie.”

There's Claude, a CIA agent, with whom the Captain, disguised as a secret police, works in Saigon, and who shows up in Los Angeles, walking an assortment of dogs for cover. Hammer, his former university professor and head of the “Oriental Studies” department, considers the Captain a kind of pet. (Sandra Oh plays his assistant and a love interest for the Captain.) Ned Godwin is a right-wing blowhard and Vietnam veteran whose congressional campaign the Captain becomes tangentially involved in. (“Delighted to have an ethnic group following the path. Do you have any other skills besides being Vietnamese?”) And finally there is Nikos, called the Author in the novel, who is making a film about Vietnam, “The Hamlet”; It's Nguyen's riff. in “Apocalypse Now” and hires the Captain as an “authenticity consultant.” Giving the Vietnamese characters some lines, the Captain suggests, would be a start.

Robert Downey Jr. as Nikos, the author, one of his four characters in “The Sympathizer.”

(Hopper Stone/HBO)

The movie-within-the-movie, which occupies an entire episode, allows for some familiar commentary on the types, practices, and pretensions of Hollywood, and the less familiar situation of the Asian actor. It features David Duchovny as a “legendary method icon”, Maxwell Whittington-Cooper as the soul singer cast in the film, and John Cho as an actor whose previous roles include “the Chinese railway worker who was stabbed by Ernest Borgnine”. [and] the Japanese soldier Sinatra shot” and plays a Korean for the first time.

As television entertainment (and it is entertainment, and a successful one, rather than a history lesson), “The Sympathizer” necessarily summarizes the plot and summarizes and externalizes the ideas that Nguyen addresses again and again in the book. (Nothing in the text suggests that Downey, or anyone else, would play four characters, but it is, you know, a concept.)

The novel takes the form of a written confession, a manuscript in manuscript form, which the Captain has been working on in solitary confinement for a year; His interlocutor gives him style notes and sends him back to do more drafts. (“Were the ghosts there as literary symbols or as genuine superstitious indulgences?”) The Captain also narrates the series, immediately addressing the audience and his editor, with comments such as: “I know what you're thinking. Yes, I am telling something that I did not actually witness. Forgive me. Some of the dialogue is conjecture, but it helps explain the events that follow” and “I don't think this scene is strange, but if it offends you, feel free to skip it.”

Aside from Duchovny, Downey is the only white actor, and one of the few non-Asian actors, who has something to do here, but it would be a mistake (note to editor) to make him a headliner. Its characters are more symbolic than anything else (in their established arrogance, immune to any kind of self-interrogation or change), while everything of real interest happens to the Vietnamese characters and within the Vietnamese community, which, obviously, does not It is monolithic, and not everything is resolved.

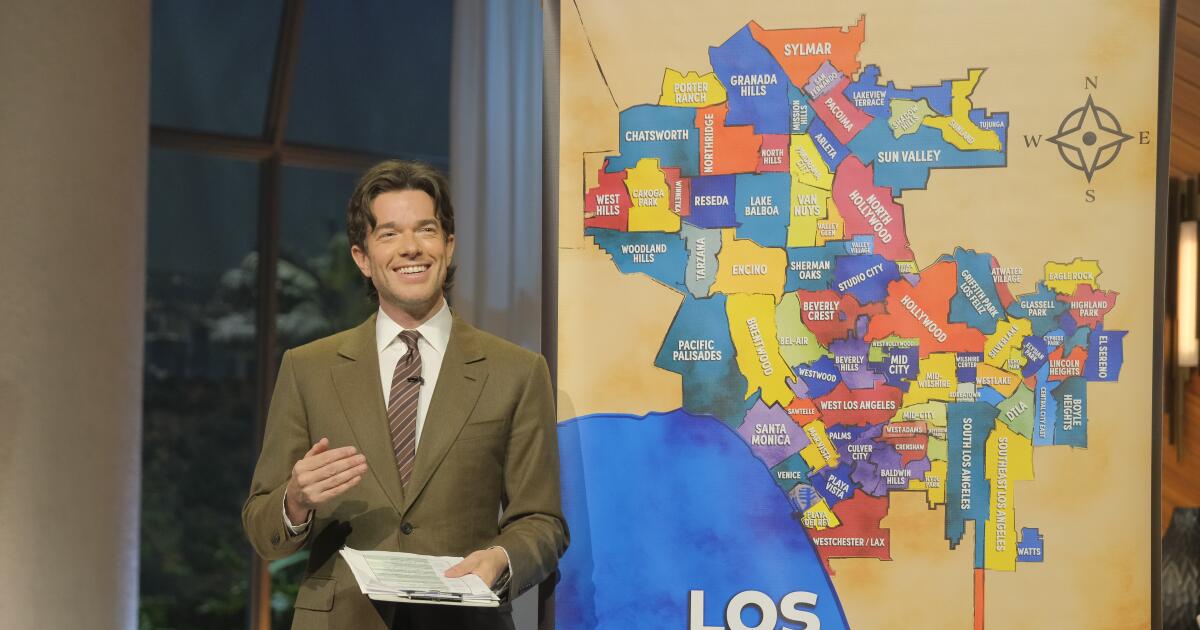

In the United States, “they eat your heart out and then complain of indigestion,” the general complains, without adapting to his new circumstances. In contrast, an enterprising former major will tell the Captain, “If you commit yourself fully to this land, you will become fully American, but if you don't, you will be nothing more than a wandering ghost living between two worlds forever.” And while the series focuses on the powerful (and formerly powerful), Park also does a good job of evoking the common, healthy community around them, establishing itself again at various events and gatherings. It's not a world we've seen in a big-budget, big-business TV series; There are more stories to tell there.