Disk! The same word takes you back to the 1970s, the decade in which it was gloriously born in the loft parties and underground clubs of New York, where it blossomed into a national obsession and entered its decadent phase, when Ethel Merman became disk. And if you don't remember the '70s, maybe you remember the parties where you dressed in your parents' old clothes and danced to their records.

It defined an era, and the three-part documentary “Disco: The Soundtrack of a Revolution,” which begins Tuesday on PBS at 9 p.m. Pacific (and is now streaming on PBS.org) links the music not only to its place in the evolution of pop but to the liberation movements of the time, as an expression, originally, of black, brown and queer subcultures, but also as a genre that gave female singers a different, more assertive and confident voice. themselves. “I will survive,” the song said, and if all this series achieves is that you hear Gloria Gaynor again or for the first time, it will have been worth it.

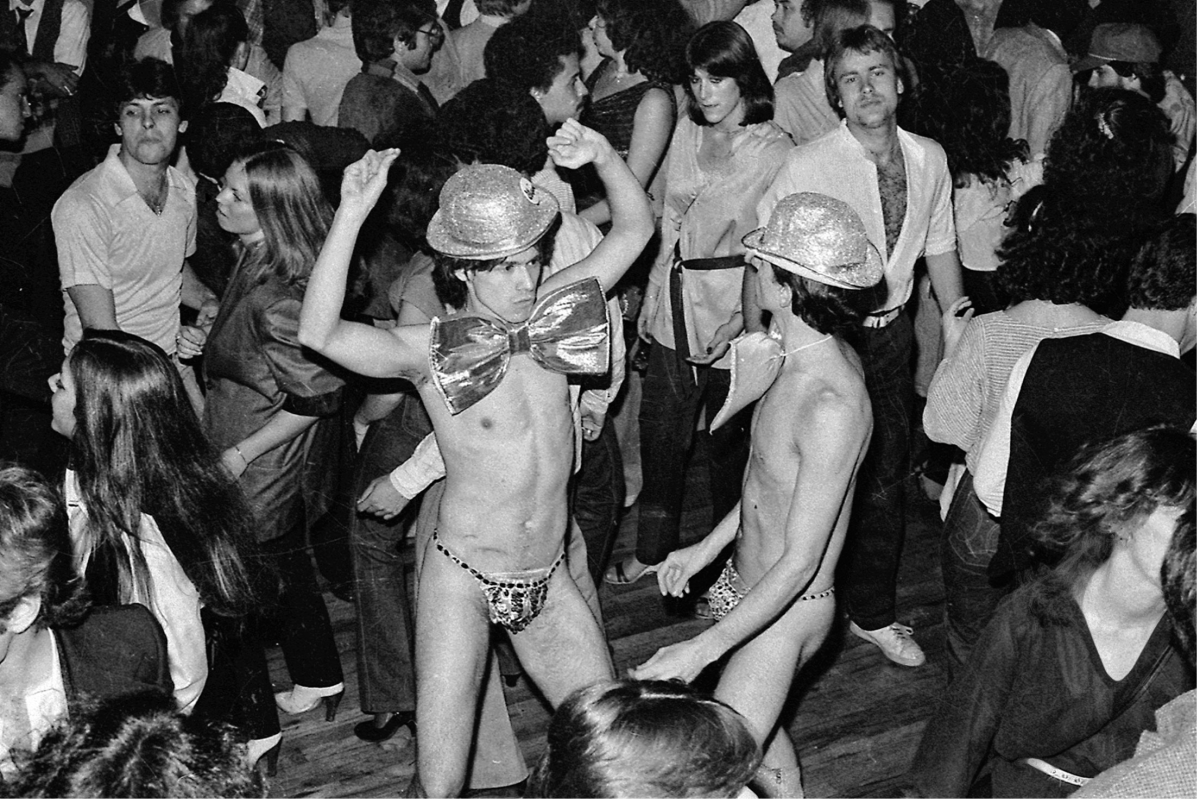

Studio 54 in New York City in 1979.

(Bill Bernstein/BBC)

Although massive success is obviously exciting and empowering for the artist, stories from music history are never more exhilarating than when they detail the creation of a new style, before money was an issue or even a possibility, when it is the expression of a community rather than the commitment of a corporation. “Soundtrack of a Revolution” captures that moment thrillingly, although, as is often the case with these types of stories, the rise is followed by a fall (the lows are here, along with the highs) and often a rebirth. . There is hardly a creative form that has not been declared dead only to sneak or roar back in some restructured but spiritually similar form. You can't maintain something as joyful and exultant, as flashy and extravagant and fundamentally democratic as the disco.

Ironically, in 1977, the year Studio 54 opened its doors to a select few, 5,000 nightclubs opened across the country. “Saturday Night Fever” premiered; Its soundtrack sold 200,000 copies a day. In a sense, it was the beginning of the end for disco: walled off by exclusion on one side and merged with the mainstream on the other. The “nightclub demolitions” that were briefly in the news (public destruction of disco records, most famously causing a riot at Chicago's Comiskey Park) were mostly a matter of straight white rock fans reacting to the heterosexual white embrace of disco music. hundreds of radio stations converted to music full time.

And so, chasing emotion, avant-garde dance music once again went underground, as “Soundtrack of a Revolution” rightly points out. Hip-hop as a local New York City phenomenon was already underway when the Sugarhill Gang's “Rapper's Delight” broke out in 1979. House music, born in Chicago, provided an electronic foundation to the post-disco disco music that has continued, through countless new subgenres and international branches, to inform dance culture to this day.

Studio 54 and the nightclub were an extension of gay life in the 1970s and early '80s.

(Bill Bernstein/BBC)

Not all artists have covers nor do you hear great songs. But “Soundtrack” hits all the important points throughout its three hours, with a compelling and, above all, very funny presentation: a mutually illuminating mix of anecdotal reminiscences, musical analysis, historical accounting and political theory. Along with interviews and archival clips, there are new interviews with singers Candi Staton, Thelma Houston, Anita Ward, Nona Hendryx and Victor Willis, the “cop” of the Village People (the gay Spice Girls of the '70s, formed from an ad seeking “Macho guys…should dance and have a mustache”); influential DJs Nicky Siano and François Kevorkian, who helped create a new career; Philadelphia drummer Earl Young, credited with creating of the four-on-the-floor disco beat; critics and clubbers; Robert Williams, whose Warehouse nightclub gave its name to disco's successor house music; and a host of activists and academics to sell the thesis of the title.

It's probably too much to say, in a cause-and-effect sense, that disco changed politics, or that politics created disco. But each movement has its signature sounds, whether it was the folk and gospel that accompanied the civil rights movement or the psychedelic music that underscored antiwar protests later in the decade. But music and movement advanced hand in hand, even as the broader culture followed at a distance.

And dance and dance music are almost by definition liberating, reaching back forever across all places and cultures, and as such have been labeled as dangerous by agents of the status quo. Sounds and footsteps change, and the inventions of one generation may be considered quaint by the next (which could be considered a kind of progress), but in their time they can shake and shake the world.