Book review

Ready for my close -up: the manufacture of Sunset Boulevard and Hollywood's dark side

By David M. Lubin

Grand Central Publishing: 336 pages, $ 30

If you buy linked books on our site, the Times can obtain a commission of Bookshop.orgwhose rates support independent libraries.

For a long time, the lists of President Trump of favorite films have consisted of gold age classics such as “Gone With the Wind” and hard -like rate as “the good, the bad and the ugly” and “Bloodsport”. However, in recent years, a new title has entered the mixture: it has routinely praise the “Sunset Boulevard” of 1950, with several reports that say it projected it on its private plane, as well as in the White House and Camp David.

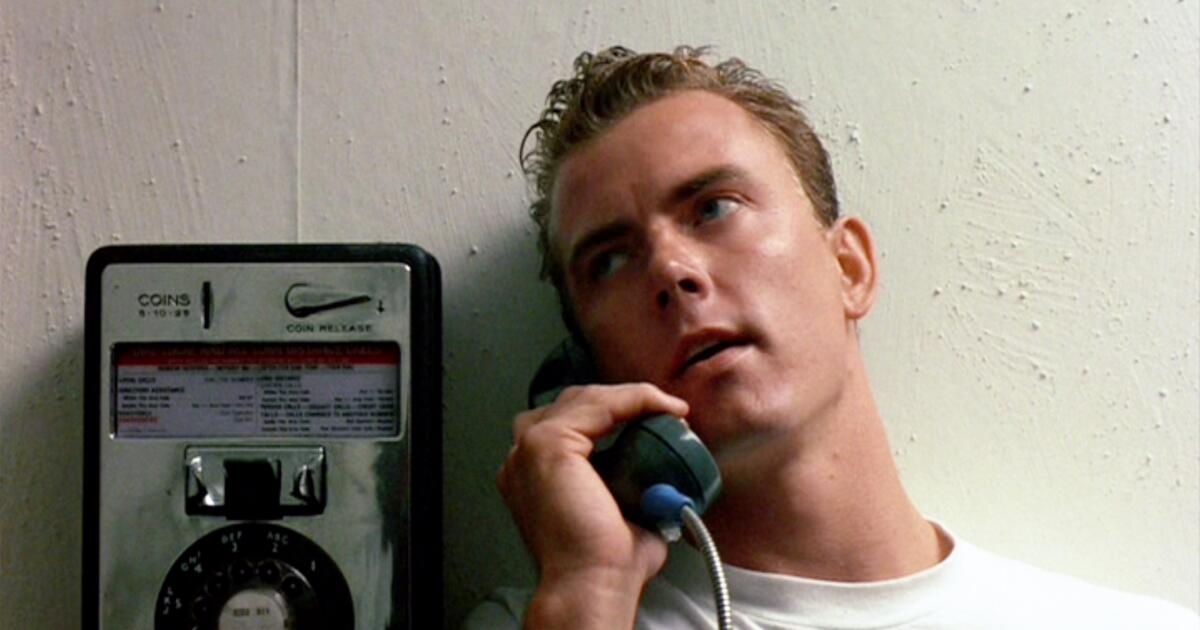

What are mostly lost these stories is what they love about the movie. With what character Trump relates more, do you think? Is the desmond norm of Gloria Swanson, the obscenely rich but discouraged star with returns and raining contempt to anyone who does not approach with loyalty and admiration abjects? Or Joe Gillis by William Holden, the opportunistic screenwriter content to compromise his moral for a payment day? Or Cecil B. Demille, the manufacturer of Kings of Hollywood whose friendly exterior disguises its determination to preserve the institutional sexism of its industry?

(Grand Central Publishing)

The power of permanence of “Sunset”, 75 years later, is due in large part to its ability to contain such crowds. It is a film that immediately celebrates Hollywood and criticizes it wildly, that is from black heart but shines with flashes of romanticism. The critic David M. Lubin recognizes with precedents those nuances in “Ready for My Searto”, his story of the film. And although the book has its deficiencies, rightly sees the film as a kind of Passey to the history of the first half century of Hollywood, warts and everything.

In many ways, the film was a sublimation of the anxieties of his career of its director/coguionist, Billy Wilder, and co -star Swanson. Born in Austria-Hungary, Wilder struggled to enter Germany's silent film industry while working as a paid dancer for rent. Upon arriving at Hollywood in the 30s, he soon dominated the bright and in the style of Lubitsch, while adopting dark songs in films such as “Double Indemnity” and “The Lost Weekend.”

Swanson, on the other hand, knew everything about the faded stardom that Norma symbolizes: in the 20s he was winning $ 20,000 per week, but did not survive the rise of the Talkies, and his first marriage, with the actor Wallace Beery, was abusive. The ferocity with which he offers his classic line: “I am great, they are the photos that were set,” was very won.

Lubin is alert to the various ways in which “Sunset Boulevard” not only observes the old Hollywood, but serves as his mausoleum. In fact, an early cut of the film begins with a scene in the morgue of Los Angeles County, while Joe Gillis suddenly sits among the fellow corpses to tell his story. (Wilder eliminated the scene after the trial audience laughed in response to it, destroying the environment of the film) chairs Gloom in the standard mansion. The infamous scene of “Waxworks” captures figures of the silent era such as the letters of Buster Keaton, his faces of pure funny alabaster. Erich von Stroheim, playing the butler of Norma, ex -husband and an emotional support ray, once a giant was once among the directors of the silent era. In the film, as Lubin, he and Swanson expresses “are the equivalent of the celestial stars, whose light reaches our eyes long after they have stopped emitting it.”

Author David M. Lubin

(Daniela Fiebel)

But Lubin also acknowledges that while the issues of “Sunset” are dark, it works in a variety of records. Remove the irrelante of the voice of Holden Patter, or his flirtatious jokes with an aspiring screenwriter (played by Nancy Olson), or his friend of the party's life (played by a “dragnet” Stardom Jack Webb) and the Soufflé Collapsan. “Part of what makes 'Sunset Boulevard' a pleasure to see is that he is always about to bow in one way or another in comedy, mystery, melodrama, social satire or horror,” writes Lubin.

It's true, but Lubin doesn't get much involved with a related question: why does “Sunset Boulevard” endure now? It survives in adaptations, parodies, pop culture references and, apparently, the White House projection room. But a four -page chapter entitled “The legacy of 'Sunset Boulevard'” barely seems to do justice to the matter. It is not just that Norma symbolizes our corrosive need for attention: “An archetypal figure that embodies our compulsive search for fame and acceptance,” as he expresses it.

Holden, in a voiceover, approaches what reveals “Sunset Boulevard” better than most films: fear. “The fact was that she was afraid of that world outside,” he says. “Fewful to remind him that time had passed,” he says. And she is not alone. Fear for the loss of status that represents the lack of script. Waxworks are images of horror shows of the consequences of fear of deterioration. Norma, fearful of its own mortality and irrelevance, accumulates it with all the money and the pages of its terrible script that it can gather.

And we, the audience, all those wonderful people in the dark, as we call us norm, looking directly at the end of the film, we have found our fears captured as well. The film challenges us to face our mortality, and see it on a giant screen offers a kind of tranquility. Look: Even celebrities and powerful are mortal. It is a general panorama, and while playing, it also allows us to feel great.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest”.