The most transcendent promise of cinema is that it can put us in someone else's shoes. But what if a film could go further and allow us to see directly through another person's eyes? And not only that but experiencing how others look at the individual whose skin we inhabit? Hopefully that kind of intimacy can lead to greater empathy.

Told primarily from the first-person point of view, director RaMell Ross' “Nickel Boys” is an experiential and experimental adaptation of Colson Whitehead's 2019 Pulitzer-winning novel.

The real-life horrors at Florida's Dozier School for Boys inspired Whitehead's source material. Founded in 1900, the institution closed its doors in 2011 after an investigation uncovered multiple cases of abuse and death and evidence of unmarked graves.

Ross's vivid reimagining of the book includes cuts from archival photographs and documents about Dozier, but its primary interest is the sensory impressions experienced by Elwood (Ethan Herisse), an idealistic black teenager raised by his grandmother Hattie (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor). ) in Tallahassee, 1960s, and Turner (Brandon Wilson), a friend Elwood meets after being falsely accused of a crime and wrongfully sent to Nickel Academy, a substitute for Dozier.

An image from “Nickel Boys”, in which you can see Ethan Cole Sharp as young Elwood.

(Orion Images)

Watching “Nickel Boys” means surrendering to its “sensitive perspective,” as Ross calls the cinematography. It means discovering the warmth and harshness of the world as Elwood (and later, as Turner does) finds it, not simply as a spectator but as if we lived it ourselves. And when other characters look directly into the camera to address Elwood or Turner, they see us through the screen.

The feat of narrative innovation has already earned Ross and his cinematographer, Jomo Fray, awards from critics groups and exclamations from the public. “Nickel Boys” is Ross’s first foray into scripted fiction following his Oscar-nominated nonlinear documentary “Hale County This Morning, This Evening,” which looks at moments of modern black life in Alabama.

“I never questioned whether it would work or not,” Ross, 42, tells me, lying on the carpeted floor of a Beverly Hills hotel suite. “Allowing [a viewer] being simultaneous with another person's experience is what is missing in the capacity of human beings to be vicarious.”

With his hands behind his head and one leg crossed over the other, the director's posture appears both tense and relaxed. The making of “Nickel Boys” required a similar balancing act: meticulous technical artifice to deliver seemingly spontaneous lyricism.

First, Ross co-wrote the script with Joslyn Barnes, also a producer on the film and “Hale County.” The couple received a manuscript of Whitehead's book from production companies Plan B and Anonymous Content before its publication in 2019.

Out of “respect and self-preservation,” Ross says, the writing duo knew from the beginning that they wanted to distill the essence of the novel without taking any images directly from its pages. To avoid comparisons based on what he accomplished and what he didn't, Ross reinterpreted the fictional character's life by filtering it through his own personal prism.

“One of the benefits of adapting the film is that I'm Elwood and Turner,” he says. “I'm a black boy. All I have to do is think about my life, what I've seen, what I've experienced and apply it to your narrative. It feels authentic because it is.”

Ross’s own “Hale County” served as a key visual and philosophical reference for “Nickel Boys.” He thought of the frames as if Elwood and Turner each had their own cameras and were doing their own version of “Hale County.” What would they focus on? This meant that writing was based on images rather than linguistics.

Ethan Herisse, left, and Brandon Wilson look at the mirrored ceiling in the movie “Nickel Boys.”

(Orion Images)

“To take the point of view very seriously and bring the camera to their bodies,” Ross says, “we needed to know how they see things, how meaning is created for them, and how that shows the person they are.” ?”

Throughout this transformation of the material, it was not lost on Ross and Barnes that the film was being produced through large companies and not completely independently. And although they remained firm in their intention to do it in first person, there were concerns about the emotional resonance that such a drama could have among viewers.

“It's a movie where, ideally, you're on the edge of your seat, leaning forward and participating, rather than just passively receiving it,” Barnes says over a video call.

At the heart of “Nickel Boys” was “the transference of love,” as Barnes puts it, between the characters: Hattie’s love for Elwood opens him to the compassionate message of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., which instills in him a greater sense of political consciousness. Hattie later embraces a more cynical Turner, allowing her to forge a brotherly bond with Elwood, their friendship being a turning point.

Ross also points out a similar transference scene in which Ellis-Taylor looks directly at us, the viewers, with the love she would look at her grandson. It is quietly revolutionary in its cinematic power, the emotional core of the film.

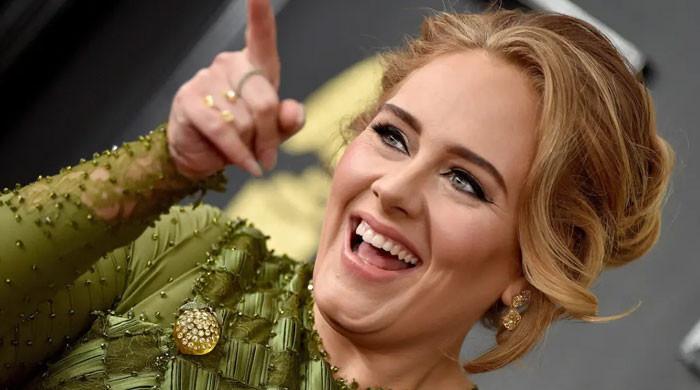

Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor in the movie “Nickel Boys.”

(Orion Images)

“Normally, as an audience, we would see her look at her grandson and we would know that she is looking at him with love, but we just know, we don't know. experience that,” says Ross. “I haven't seen a person look through the lens into the soul of the audience with that kind of love.”

But because the eyes through which we look are those of a black teenager in the Jim Crow South, often the “returned look,” as Barnes refers to how others view Elwood and Turner, is one of racist prejudice. . From the beginning, we witness the severity with which a white police officer stares down young Elwood just for crossing his path.

“People have been doing POV forever, like 'Hardcore Henry,' but that's not something that happens within the drama of other people's lives, and specifically within the race of other people's lives,” Ross says.

For viewers who do not come from racialized identities, being in this position might be a novelty, ideally combined with a new sense of solidarity, but for those intimately familiar with Elwood's lived experience, watching “Nickel Boys” can evoke complicated emotions.

Ross believes that a black person (and other people of color) watching the film, which places them within another black person's worldview, could actually amplify their own experience.

“You say, 'I finally see myself represented in the most personal way, from within,'” Ross explains. “But then you're also almost retraumatized.” With that in mind, Barnes and Ross deliberately avoided showing physical violence on screen.

Cinematographer Fray, speaking over Zoom from New York, was eager to try it and break what he calls the “membrane” between the audience and the story on screen in mainstream cinema. This separation prevents the viewer from fully connecting with what they are seeing. “Nickel Boys” denies this.

The producers suggested Fray to Ross as a possible collaborator. During their first meeting, Fray shared his intention to make the film look like Ross's famous work in large format photography. That informed and unselfish comment convinced the director.

“What RaMell always sought was to try to create an immersive experience,” explains Fray, “to invite the audience not only into the idea of the hostility of the Jim Crow South, but also to invite them to enter the very bodies of young black men, to feel them.” what it feels like to travel the world like them.”

Some of the references Ross and Fray discussed were Terrence Malick's stunning “The Tree of Life” and the grueling medieval Russian science fiction masterpiece “It's Hard to Be a God.”

The result was a rigorous list of intentionally designed stunt shots: “maybe 35 or 36 pages, single-spaced,” Fray recalls, “meticulously describing every turn, tilt, gesture or movement of the camera.”

Each scene was conceived as a long take or “one”, a continuous uninterrupted and unedited shot. The way they were executed varied. It was mainly Fray, Ross and cameraman Sam Ellison moving around the spaces.

“The difference between carrying the camera on your shoulder and holding it in your hands is that the latter feels more like a head resting on your neck,” says Fray. “You can turn and make really quick adjustments in a way that you can't physically do with the camera on your shoulder.”

The actors, whether Herisse or Wilson, would stand close to the person operating the camera, not only to draw lines but to capture their hands in the frame touching objects or interacting with their co-stars.

On some occasions, the two protagonists used custom rigs that attached the camera to their bodies for a hypervisceral effect. Elsewhere, the filmmakers used a SnorriCam, a different camera device, attached to the older Elwood (Daveed Diggs) and filming him from behind, to convey the dissociative, out-of-body experience that trauma can inflict on survivors.

Whoever was operating the camera was essentially Elwood or Turner. “As a cinematographer, this put me in a fundamentally different relationship with creating images,” says Fray. “When the camera hugs a character, I'm the one they physically hug and you feel that intimacy.”

One example that revealed to Fray how transformative this narrative approach could be was Ellis-Taylor.

“Aunjanue is out of the books,” Fray recalls. “He knocks on the table and just says, 'Elwood, look at me, son.' That's when I went from camera operator and director of photography to scene partner. “She needed me, as Elwood, to understand what she was saying, so my camera goes back up and makes eye contact with Aunjanue.”

Since its premiere at the Telluride Film Festival, “Nickel Boys” has inspired passionate reactions.

“I don't know if it's the form of the film, if it's a point of view, if it's the specific images or sounds,” Ross says. “You imagine it's all those things combined, but no one has said even remotely the same thing after seeing it. “It always provokes a subjective response.”

For all its formal audacity, “Nickel Boys” has a humanist essence. Hopefully, once the camera closes its blinking eye, the audience will feel like they know these characters better than they could ever imagine knowing another.