Oz Perkins is no stranger to the public. His parents, model Berry Berenson and “Psycho” star Anthony Perkins, were famous. He’s no stranger to darkness, either: His father was forced to live a life in the closet, and his mother died on one of the hijacked planes during the 9/11 terrorist attacks. That’s a lot for one person’s family history to take in.

Perhaps that’s why horror movies have always been a part of Oz Perkins’ life. His fourth film, “Longlegs,” is his scariest. It follows FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) as she hunts down an Oregon serial killer (Nicolas Cage). It’s destined to be a breakthrough for the director, thanks in part to a Herculean marketing campaign by distributor Neon. It’s also completely terrifying, creating an atmosphere of unrelenting dread.

One of Perkins’ most formative experiences was watching Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining.” He remembers the first time he saw it. “We used to spend summer vacations in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and we would watch it in a house with glass walls, and you could see the forest,” the director, 50, recalls via Zoom call from his home in Los Angeles. “I remember trying to sleep with that backdrop. It was a tough night.”

When it comes to writing scripts, Perkins always draws on her own experiences. “I made a decision early on that the characters were going to replace me in one way or another,” she says. The description of the glass-walled house where she watched “The Shining” is not unlike the one Monroe’s Harker inhabits in “Long Legs,” and her ability to see only a certain distance into the woods is a key aspect of one sequence.

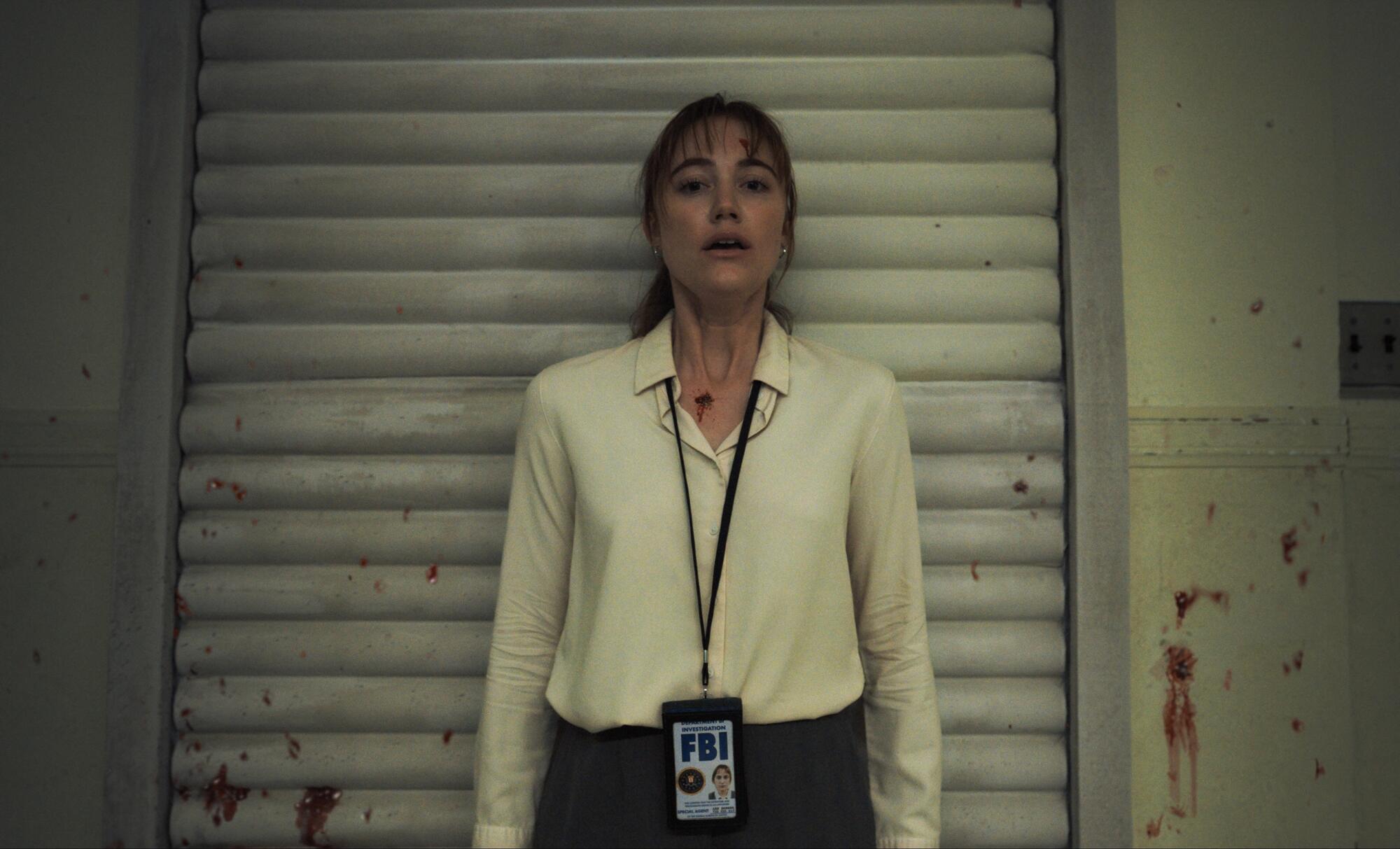

A scene from the movie “Longlegs.”

(Neon)

Her second feature, the haunting, slow-burning 2016 ghost story “I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House,” was dedicated to her father and even includes a clip from Perkins’ Oscar-nominated performance in William Wyler’s “Friendly Persuasion.”

“It was about how we want to know who our parents are, and sometimes we don’t feel that desire until they’re gone,” she says. “It can be impossible to know who someone is when they’re no longer around.”

“Longlegs,” written and directed by Perkins, is about how “our parents can build a story. It can be an old story that is part of family tradition for generations, but it can also be generational karma that is passed down through generations, something that needs to be dealt with and explained. A secret or a challenge that can be hidden.”

That imposed secrecy, especially when it came to his father, had an unmistakable effect on Perkins that continues to influence his work. “I think when you live in that environment where there’s all the truth, the hidden truth, and the version that you’re given,” Perkins says, “it creates layers of mystery and intrigue and curiosity. And that’s what I’ve tried to convey in the images that I make.”

Perkins has fond memories of his father. He has seen all of his films, though they did not watch them together. (“If your father is a dentist, they don’t take you to look at people’s mouths,” Perkins says harshly.) Rather than bonding through movies, father and son found affinity in their shared sense of dark humor. “In his circles, my father was known for being a very funny person and for approaching things with an abstract, surreal sense of humor,” Perkins recalls. “And I’m proud to be able to express that, especially in the movies I make, which I sometimes find very funny.”

Maika Monroe in the movie “Longlegs”.

(Neon)

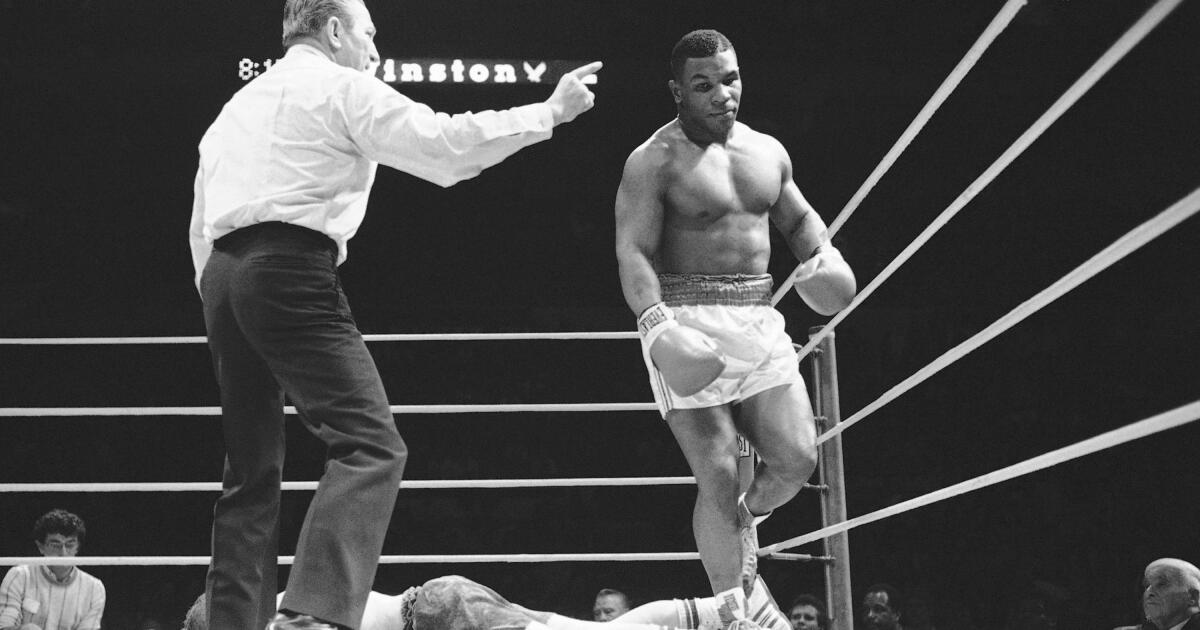

Horror thrives on the unexpected. “Longlegs” draws you in with its familiarity before plunging you into something more relentless. Set in the 1990s and centered on an intuitive but inexperienced female protagonist, its closest comparison is Jonathan Demme’s “The Silence of the Lambs,” a resonance Perkins uses to her advantage.

“The idea was to take the success of The Silence of the Lambs and use it to do something radically different,” says Perkins. The idea of using a film as dark as Demme’s film as a palate cleanser for Long Legs demonstrates just how unpalatable Perkins’ film is.

Although the thriller builds up its atmosphere over time, the scares are present from the start. It's a deliberate decision by Perkins. “We want to make sure the audience is with us as soon as possible,” he says.

It's a lesson he learned from the great filmmaker Mike Nichols, who took Perkins under his wing after his father died in 1992 when Oz was 18. Perkins says, “Mike showed me that as a director, you have the ability, the power and the opportunity to plant a point of view in everything you do, and if you want to give your film body, texture and depth, it's essential.”

Perkins looked beyond the horror genre to establish the film’s unique visual style, turning cinematographer Andres Arochi toward the work of director Gus Van Sant. “If you plant the seed of something unexpected,” Perkins says, “you automatically get artists interested in another channel. ‘My Own Private Idaho’ is going to be a much bigger reference than ‘Rosemary’s Baby.’”

Even though Perkins’ movies are terrifying, actors love working with him. “Oz’s filmmaking style is relaxed, humble and confident, with a hint of wry humor,” writes “Longlegs” co-star Blair Underwood via email. “His dash of humor is the icing on the cake to create a creative, confident and daring working environment.”

“He lets his work breathe through others and doesn’t hold on to it so tightly that he strangles it,” Monroe adds.

That sense of freedom is exactly what drew Cage to deliver truly inspired work as protagonist Long-Legs, a deeply unnerving performance (even for him). He lives in a dark lair with a T. Rex poster. His hair is long, lank, and gray, his makeup is a corpse-white, and prosthetics make his face mask-like and practically inhuman. Long-Legs suddenly breaks out into chilling fits of song. Cage is unrecognizable with a raspy, high-pitched voice; you'd be forgiven for having no idea he was in this.

It’s the kind of role that requires total commitment, and that’s exactly what Cage delivers. “It was clear that he’s a deliberate, careful, thoughtful, focused actor (and human being),” Perkins recalls thinking during their first meeting.

They found themselves bouncing ideas off each other at all hours, with Cage sending Perkins voice memos with possible options for Longlegs well into the night. “We were just doing it together all the time,” the filmmaker says. “Nic doesn’t worry about himself. He likes to collaborate as much as anyone I’ve ever met.”

While filming “Longlegs,” Cage didn’t want to mingle with the cast or crew after each day of shooting, instead concentrating entirely on his role. Not in the usual actor-centric way, Perkins assures me, but because that isolation made for one of the film’s most heartbreaking scenes: Longlegs and Harker meet for the first time. That was also the first time Monroe met Cage. She had no idea what he would look like, sound like, or act like.

“I felt like I was charging the battery to have the opportunity to capture real emotion and presence in a scene,” says Perkins. Thanks to Cage's commitment, they were able to capture a moment of genuine poignancy and spontaneity that is sure to shake audiences.

Perkins has already filmed his next movie, “The Monkey,” based on a 1980 Stephen King short story. But preparing for another full-on foray into the horror genre would be a mistake, he insists.

“The Monkey is nothing like Longlegs,” Perkins assures me. He describes it as a comedy “with a lot of really extreme cartoon gore” and mentions An American Werewolf in London, Gremlins and Death Becomes Her as references.

Perkins is also back in action in “The Monkey,” something he hasn’t done since Jordan Peele’s “Nope.” His first role was as young Norman Bates in 1983’s “Psycho II.” Typically, he’s nervous about acting without control, so he’s largely moved to working behind the scenes.

For Perkins, though, one gets the sense that challenging himself as much as the viewer is part of the fun. “That’s the game, isn’t it?” he says. “Give them what they want.” No “They think they want to.”