On the same day that former President Trump told a national gathering of Black journalists that Vice President Kamala Harris “was Indian through and through, and all of a sudden she turned around and became a Black person,” his running mate, Sen. J.D. Vance, accused Harris of being a “phony” who “grew up in Canada” (she attended high school in Montreal) and used “a fake Southern accent” at a rally.

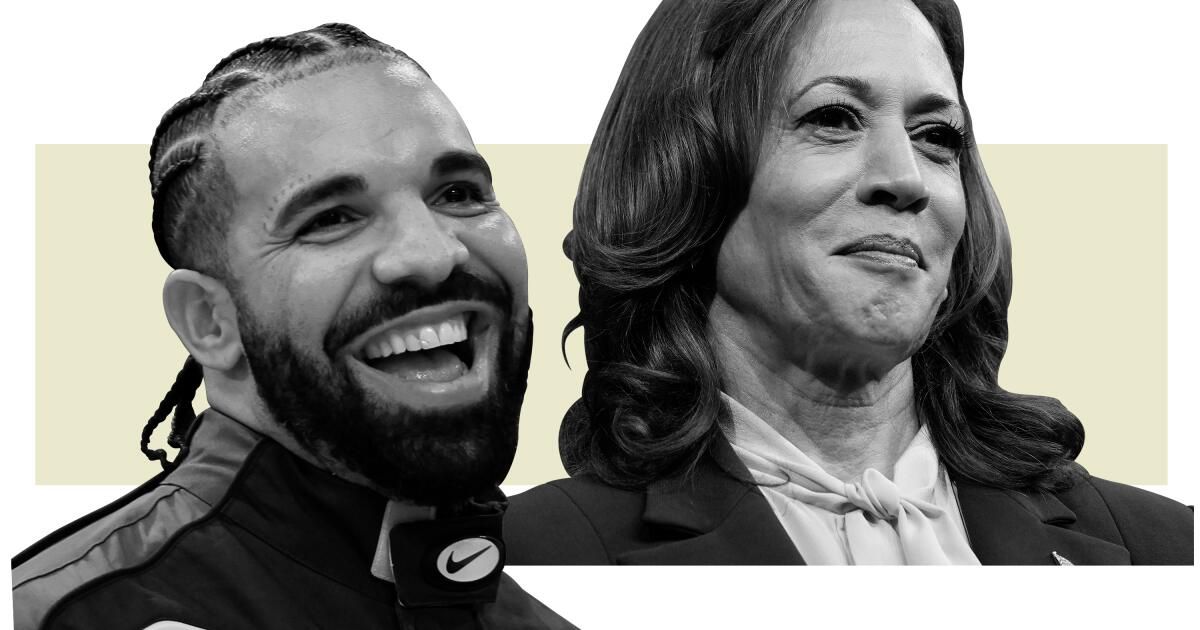

The accusations from both men sound eerily similar to those made by rapper Drake about fellow hip-hop titan Kendrick Lamar (and many others) in a rap feud whose effects linger. Drake has been accused of being a “colonizer” whose Canadian identity and enthusiastic embrace of diverse aspects and accents from a wide range of black culture make him racially suspect.

These arguments, whether made by white men with racial issues or black icons, deny the complexity and diversity of blackness.

Trump and Vance have little understanding and even less respect for the multiracial strains and complex cultural mixes of black identity. Harris has acknowledged from the beginning her Indian heritage and Jamaican roots. In our national context, biracial blackness has always encompassed a multitude of skin types, light or dark, Caucasian or Indian and many more.

Millions of black Americans, because of a history of slavery that conservatives tend to ignore, have all kinds of ethnic blood in their veins and all kinds of figures on their family trees: a grandfather who was Native American rests on one branch, a great-grandmother who was Irish on another.

The one-drop rule of black identity reflects the reductionist compulsion in American racial politics: every body genetically shaped by white and black ancestors has been seen as contaminated and inferior and labeled black. The same often happens with black bodies mixed with Latino and Asian identities.

Yet many mixed-race people take pride in their one-drop black identity. Harris’s Indian mother knew she was raising black daughters, but they often wore saris and visited India. Like millions of black people, she understood the various expressions of blackness.

Trump’s argument that Harris transitioned from her Indian identity to her black identity also contradicts the facts of Harris’s biography, her education at Howard University, and her affiliation with the black sorority Alpha Kappa Alpha. Trump’s narrative that black people prostitute their race for social gain appeals to those who believe black progress comes at the expense of white prosperity. Vance’s vacuous expression reflects his strident, false white resentment of Harris’s cosmopolitan blackness.

Ironically, that cosmopolitan vision of blackness is at the heart of the Lamar-Drake feud. Their dispute — which is playing out fiercely this spring in a series of releases — is a battle over cultural cachet, racial authenticity and group pride, and exposes a parochialism that undermines hip-hop’s global currents.

In his hit “Not Like Us,” Lamar accuses Drake of being a “colonizer” because Drake supposedly “ran”[s]” to Atlanta to partner with some of his trap music's paragons to reinforce his blackness. Lamar's argument echoes longstanding criticism that Drake's biracial Canadian roots make him suspect as a genuine black artist. Drake's artistic experimentation with different accents and musical genres has led many to claim, as Vance did with Harris, that Drake is a fake.

Lamar's conflict with Drake is rooted in a parochial and claustrophobic view of blackness.

Drake grew up in Toronto, the son of a Canadian-Jewish mother; he spent summers in Memphis, Tennessee, with his father, an African-American musician. His artistic tastes were deeply influenced by a broad swath of the black diaspora: Afro-Caribbeans, Londoners, American Southerners, especially from Memphis, and Torontonians. Toronto's multicultural makeup, with its sizable Italian, Portuguese, Jamaican, and Filipino immigrant populations, also fueled his musical appetite.

The argument that Drake is somehow a culture vulture who appropriates strains of black culture misconstrues not only his influences, but also hip-hop as an art form with universal reach. Drake's critics attempt to confine him, and black culture more broadly, to the United States, which received far fewer blacks in the slave trade than, say, Peru, Mexico, Brazil and Jamaica.

Interestingly, the attempt to define him as a colonizer overlooks the fact that black people in America often believe that our blackness is superior to that of other black people, a colonial view in itself far more problematic than anything else Drake could be accused of. And given that Canada offered a prominent path to freedom for those escaping American slavery, it feels downright bizarre to paint Drake as an outsider or an enemy of hip-hop because he’s Canadian and not from Compton or Detroit.

At a Trump rally in Charlotte, North Carolina, a white female commentator attempted to remind Black Americans that Harris is “not one of you.” Lamar’s “Not Like Us,” unfortunately, is driven by the same limiting racial logic. As we fight to expel the racially troubling ideas and mischaracterizations Trump and Vance are expressing about Kamala Harris, Black people must be careful not to allow those same ideas to enter the back door of our culture.

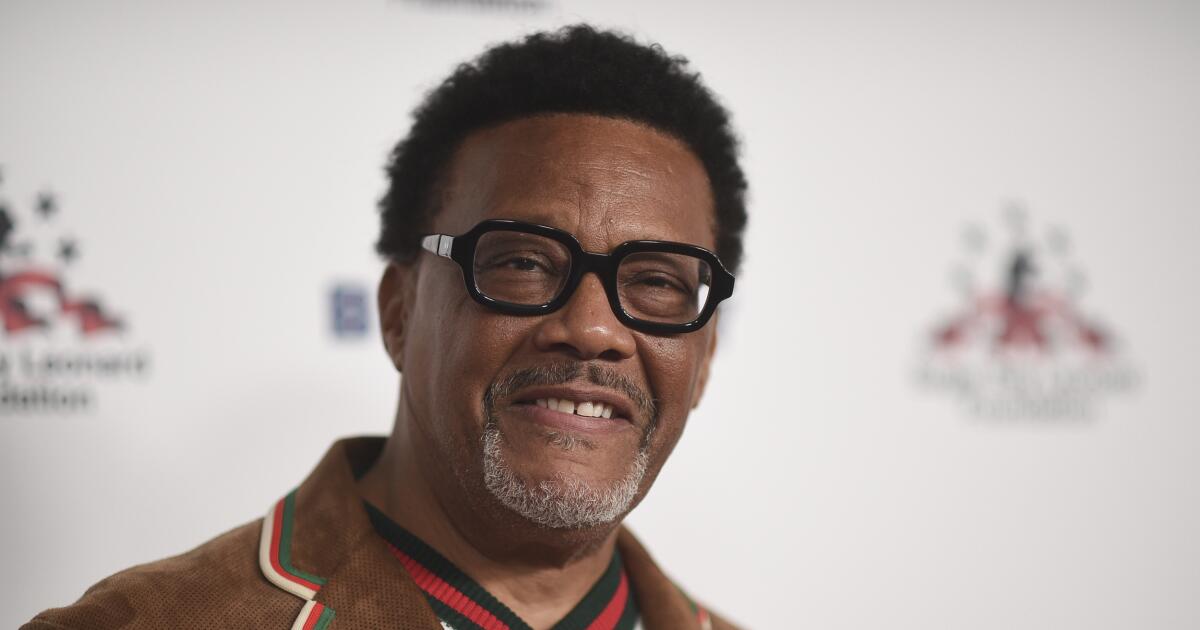

Michael Eric Dyson is a professor of African American studies at Vanderbilt University and the author, most recently, of Entertaining Race: Performing Blackness in America.