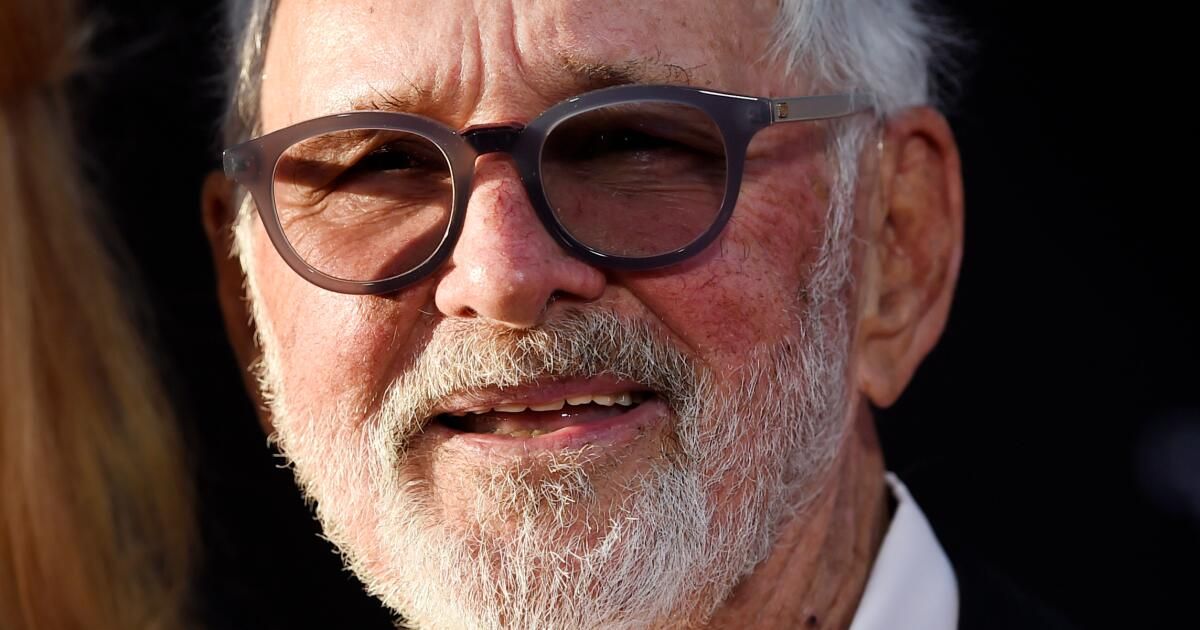

Norman Jewison, a prolific and highly honored producer and director whose films ranged from the romantic comedy “Moonstruck” to the drama “In the Heat of the Night,” which won the best picture Oscar in 1968, has died.

Jewison, who also directed the Doris Day comedies and the quirky 1966 film “The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming,” died Saturday at his home, publicist Jeff Sanderson confirmed to The Times in a statement. He was 97 years old.

“Norman Jewison was a vibrant force in the film industry for more than four decades,” the statement said. The cause of death was not revealed.

Jewison produced or directed more than 40 films, beginning with a Tony Curtis light comedy, “40 Pounds of Trouble,” in 1962 and ending with the 2003 thriller “The Statement.”

Among the other films he produced and directed were the popular 1968 caper film “The Thomas Crown Affair,” with Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway; two highly regarded musicals from the 1970s, “Fiddler on the Roof” and “Jesus Christ Superstar”; the futuristic “Rollerball,” from 1975, starring James Caan; “And justice for all”, from 1979, starring Al Pacino; “Best Friends,” a 1982 romantic comedy with Burt Reynolds and Goldie Hawn; “Agnes of God,” a 1985 religious mystery starring Jane Fonda; the 1989 post-Vietnam War melodrama “In Country”; “Other People's Money,” a 1991 comedy-drama with Gregory Peck and Danny DeVito; and “Only You,” a 1994 film about romantic destiny starring Marisa Tomei and Robert Downey Jr.

“Moonstruck,” released in 1987, may be his most popular film. But he considered his three films about racial prejudice to be the most important.

In addition to “In the Heat of the Night,” starring Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger, there was “A Soldier's Story,” the 1984 film that was nominated for best picture and gave Denzel Washington a breakthrough role, and 15 years later , “El Huracán”, which also starred Washington.

Born on July 21, 1926, in Toronto, the son of merchants, Jewison studied at the Royal Conservatory of Music and Malvern Collegiate Institute in Toronto before serving in the Canadian navy during the Second World War. During a 60-day leave, he hitchhiked through the southern United States during the Jim Crow era and witnessed segregation up close for the first time. At one point, he was thrown off a bus for sitting in the section reserved for black passengers.

“I barely missed witnessing a lynching in a city,” he told The Times in 1985. “I didn't know then that I would ever make movies, but all of this stayed with me.”

Seeing racial discrimination in the South also struck a chord with him in his youth, when he was mistaken for Jewish because of his name. (He was born into a Protestant family). He said he was proud to have been beaten along with his Jewish friends.

After the war, he earned his bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto's Victoria College and began performing on stage and on the radio while driving a taxi. He later moved to London, where he wrote and performed for the BBC, returning to Toronto to direct television programs for the CBC in Canada and later for CBS in New York.

For CBS, Jewison directed “Your Hit Parade” and a handful of musical variety shows with stars such as Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, Andy Williams, Danny Kaye and Harry Belafonte.

He had won three Emmy Awards when he made “40 Pounds of Trouble,” starring Curtis and Suzanne Pleshette. The job came about after Curtis observed Jewison directing a rehearsal for a Garland television special that also featured Curtis' friend Sinatra.

“You do a good job, kid,” Curtis told Jewison. “When are you going to make a movie?”

Jewison, telling this story in his 2005 autobiography, “This Terrible Business Has Been Good to Me,” said that when he resisted, Curtis added: “Movies, television. “They are just cameras.”

“40 Pounds” led to a contract with Universal, for which Jewison made two romantic comedies with Doris Day: “The Thrill of It All” and “Send Me No Flowers.”

But he considered “The Cincinnati Kid,” which he took over when Sam Peckinpah was fired, the first film that was truly his. The film, starring McQueen and Edward G. Robinson, was released in 1965 and earned positive reviews from Jewison.

Jewison's next film was his first big hit: “The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming,” a 1966 Cold War comedy starring Carl Reiner, Eva Marie Saint and Alan Arkin about a Russian submarine that lands off the New England coast. The film took American audiences by surprise with its humane and comical vision of people usually portrayed as stern enemies. “Russians,” the sixth film Jewison directed and the first he produced, earned him a best picture nomination.

“If 'The Cincinnati Kid' was the film that made me feel like a filmmaker, 'The Russians Are Coming' was the film that gave me a strong anti-establishment reputation,” Jewison wrote in his autobiography.

The following year came the first of Jewison's most important films on race relations: “In the Heat of the Night.” Producer Walter Mirisch, who wanted to make a film of the story based on a novel by John Ball and a screenplay by Stirling Silliphant, initially resisted when Jewison expressed interest in directing “Heat.”

“He thought it was too small for me,” Jewison said in an interview years later, laughing at the memory. “But I was absolutely passionate about making the film.”

Mirisch eventually agreed, but also imposed a tight budget. Jewison economized by having his cinematographer use a handheld camera instead of more sophisticated equipment. He also changed the name of the location where the story takes place to “Sparta, Miss.,” allowing him to use billboards in Sparta, Illinois, the small town not far from the Mississippi River where “Heat” was actually filmed.

Illinois, not the Deep South, became the location for “Heat” because Poitier refused to film south of the Mason-Dixon line. Earlier that same year, Poitier and Harry Belafonte were forced into a car chase in rural Mississippi, and Poitier “had no desire to expose himself to white Southern hospitality again,” Jewison said.

Although the film explored the ugliness of racism, it also served as “an entertaining and somewhat messy comedy-suspense,” wrote critic Pauline Kael in Harper's. She suggested that both white and black audiences understood and enjoyed the racial humor of the “witty and hyper-educated black detective explaining matters to the backward and clumsy Southern police chief.”

Jewison was proud that the film put on screen the first black character in a movie “who came out in a $500 suit and was smarter than anyone else in the movie.” But he seemed almost bewildered by the film's popularity.

“It was about black-white relations, and that was the center of the civil rights movement,” the still-bewildered Jewison said in an interview nearly 40 years later. Nominated for seven Oscars, “Heat” won an Academy Award for producer Mirisch for best picture and Steiger for lead actor, as well as Oscars for screenplay, film editing and sound. But although Jewison was nominated for directing, he lost to Mike Nichols of “The Graduate.”

After bringing two Broadway musicals to the screen: “Fiddler on the Roof” (1971), which was nominated for eight Oscars, including best picture, and “Jesus Christ Superstar” (1973), by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, Jewison returned to the racial issue. He issues with “A Soldier's Story.” The film is a melodramatic story starring Washington, who had appeared in the off-Broadway production of “A Soldier's Play,” as the outspoken recruit who kills his sergeant major.

Jewison's third film in the trilogy of race-related films was “The Hurricane” (1999), with Washington as Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the boxer wrongfully imprisoned for murder. At its premiere, Washington, who was nominated as lead actor for the role, said that until then he had not fully appreciated what a good director Jewison was.

“There is a simplicity in [it]Washington told the New York Times. “He knows what he wants. He is a true director of actors.”

“Hurricane” completed the trilogy that represented Jewison's more socially conscious side. He once said that, although he hoped his work was not “a message”, he believed that films “should bring people together and not separate them”. His political views sometimes led him to make dramatic personal statements. In the early 1970s, Jewison left the United States in disgust and moved to London.

“I was losing my sense of humor,” Jewison told the New York Times in 1999. “I had marched. The Vietnam War was underway. Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated. Reagan was governor. Nixon was president. “I turned in my green card and moved.”

It was while he was in Europe that he made “Fiddler on the Roof,” “Jesus Christ Superstar,” and “Rollerball.”

“And then I got over it,” he said of his anger at America. “It wasn't the American people he was angry with, but with the times and the leadership.”

He returned to Canada in 1979. Eight years later, “Moonstruck” became a surprise hit.

Jewison loved John Patrick Shanley's script for “Moonstruck,” which was full of “verbal cascades” for the film's stars, Cher and Nicolas Cage. He also loved the idea of “the moon,” the full moon shining over Manhattan and Brooklyn.

“But what really interested me is the central idea of betrayal, which, come to think of it, has figured in a lot of my movies,” Jewison told the LA Times in 1987. Cher's Loretta betrays her fiancé by falling in love with his brother; Loretta's mother (Olympia Dukakis) betrays Loretta's father (Vincent Gardenia) by encouraging a local teacher to kiss her goodnight.

“And all of this seems to be out of the characters' control,” Jewison said with delight.

“Moonstruck” won a leading actress Oscar for Cher, a supporting actress award for Dukakis and a screenwriting Oscar for Shanley.

In 1998, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences presented Jewison with its highest award: the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, which is given to a producer. In 1988, Jewison helped form the Canadian National Center for Film Studies in Toronto, the Canadian equivalent of the American Film Institute.

After leaving England, Jewison maintained a home in Malibu but lived primarily on Putney Heath, a 200-acre farm in the Caledon Hills northwest of Toronto that supports commercial livestock and maple sap operations. His wife of 51 years, Margaret Dixon, known as Dixie, died in 2004. He is survived by his wife Lynne St. David-Jewison, three children and five grandchildren.

The statement said celebrations of Jewison's life will be held in Los Angeles and Toronto at a later date.

Luther is a former Times staff writer.