As a general rule, Nick Cave advises against “attributing a strict life narrative” to the records a musician puts out. Songwriters are storytellers, after all, and few have demonstrated more interest in age-old themes and dramas (justice, violence, sex, betrayal, redemption) than Cave has in the nearly half-century since he left his native Australia, first with his band Birthday Party and then with the Bad Seeds.

Yet Cave, 66, acknowledges that his work in recent years “almost exactly” mirrored events in his real life — namely the death of his 15-year-old son, Arthur, in an accidental fall off a cliff near the family home in Brighton, England, in 2015. Albums like the following year’s “Skeleton Tree” and especially 2019’s spectral “Ghosteen” “follow a development through grief,” Cave says, “because that’s just what happened to me.” In 2022, the singer lost a second son when Jethro, 31, was found dead of unspecified causes.

“Wild God,” Cave’s new album with the Bad Seeds, “has at its core a fundamental understanding of the suffering we go through as human beings,” he says. “But it’s also a joyous record” — a vibrant set of vigorous, poetic rock songs that showcase the sympathetic interplay between Cave and his backing band (which here includes Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood). Cave called in from New York to talk about the LP, his attraction to the church and the illusory promise of his own sex appeal.

You and your wife, Susie, moved to Los Angeles from Brighton for a while after your son Arthur died. I understand the need for a change of environment. Why Los Angeles?

I have always loved America, in some ways it is the country I love the most, but for a long time I didn't really understand Los Angeles, I couldn't understand its geography. Susie always loved it, so we spent our holidays there and eventually we decided to leave Brighton, where there was a lot of sadness for us, and go somewhere bright and sunny.

What part of the city did you land in?

In the Hollywood Hills, a place near Outpost Drive. I lived in Los Angeles in a very different way during that period because I had a lot of creative friends who were eager to hang out and exchange ideas. The sculptor and painter Thomas Houseago had a huge studio in Frogtown and I used to go there and hang out. And there were some actors and filmmakers—I won’t go into details—who we would meet up with on Saturday or Sunday nights at different people’s houses to eat together and just talk about stuff. I really treasured those evenings.

Has spending time here shaped the way you think about wealth or success?

I'm from Australia, where if you lift your head too high, they cut it off at the neck. There's an aspirational aspect to Los Angeles that I quite like. Maybe it's because I'm a successful person. [Laughs].

In “Wild God” you talk about finding joy. Did you ever feel like you were betraying your son in pursuing that joy?

That's a huge trap that grieving people fall into. I don't believe it at all. I think when things like that happen to us – and it's something that most of us will go through in one way or another – I think it's imperative that we turn to the happiness that we can find, even if it's just to influence the condition of those who have died. My biggest concern, strange as it may seem, was my concern for my son, wherever he is – the feeling that he might have for the pain that his death caused his parents and other family members. So I felt on some level that it's for He made us look for a way to relate to the world that had meaning and joy.

I recently spoke with Jack Antonoffwho told me that his band Bleachers' latest album is the first one that doesn't deal with the loss of his younger sister when he was a child. For years he believed that everything that went wrong in his life was somehow related to that tragedy. Does that make sense to you?

It makes sense, but I don't see things the same way. Terrible things don't happen to you after you lose a child. You can lose another child, that's the terrible thing. But, in essence, the world has done the worst it can. I've seen it with my wife. She had a company, The Vampire's Wife, that made extremely beautiful dresses that really came out of her desperation. [over Arthur’s death]And this company went under a few months ago. This should affect Susie terribly, but in a way she is immune. The pain has hardened us.

Are you stronger than you ever thought you would be?

I would say hardened, a little different from hard.

It is clear what it means to lose children. affected Your job. Did having children change it?

Yes. The idea of childhood is a common thread that runs through a lot of my songs, from songs about our inability to protect our children, like “O Children,” to something like “Papa Won't Leave You, Henry,” which I wrote while cradling my newborn son and rocking him to sleep. These are the monumental things that expand the potential of the heart.

In addition to the Bad Seeds' performance, the new album features plenty of choral singing.

I spend a certain amount of time in church, and part of that is because the music is extraordinary. Sacred music, plain music, big choirs… it's all extremely beautiful, and I wanted to try to include some of that on this record.

Rock musicians use the term “gospel choir” quite indiscriminately. Is that how you would describe the singers in the song “Frogs”?

I was actually trying to get the chorus on that particular song to sing as white as possible, even though there were like 20 black people, because I wanted to have a kind of heavenly, high church feel, whereas something like “Conversion” is much more black gospel. But I didn’t want to hire two choirs. [Laughs]There's a kind of awkward relationship between gospel music and rock music that I don't really like. It can be very cheesy. So the way we approached recording “Conversion” was to do a kind of call and response that was completely chaotic and a little bit off-key, just to give it a certain frenzy.

Do you find any kind of nourishment in church music?

Of course. Hearing those things does something to the spirit. But I find great comfort in going to church for all kinds of reasons, not just for the music. It's probably one of the few places left for us where we can take our various sorrows and feel them fully and safely.

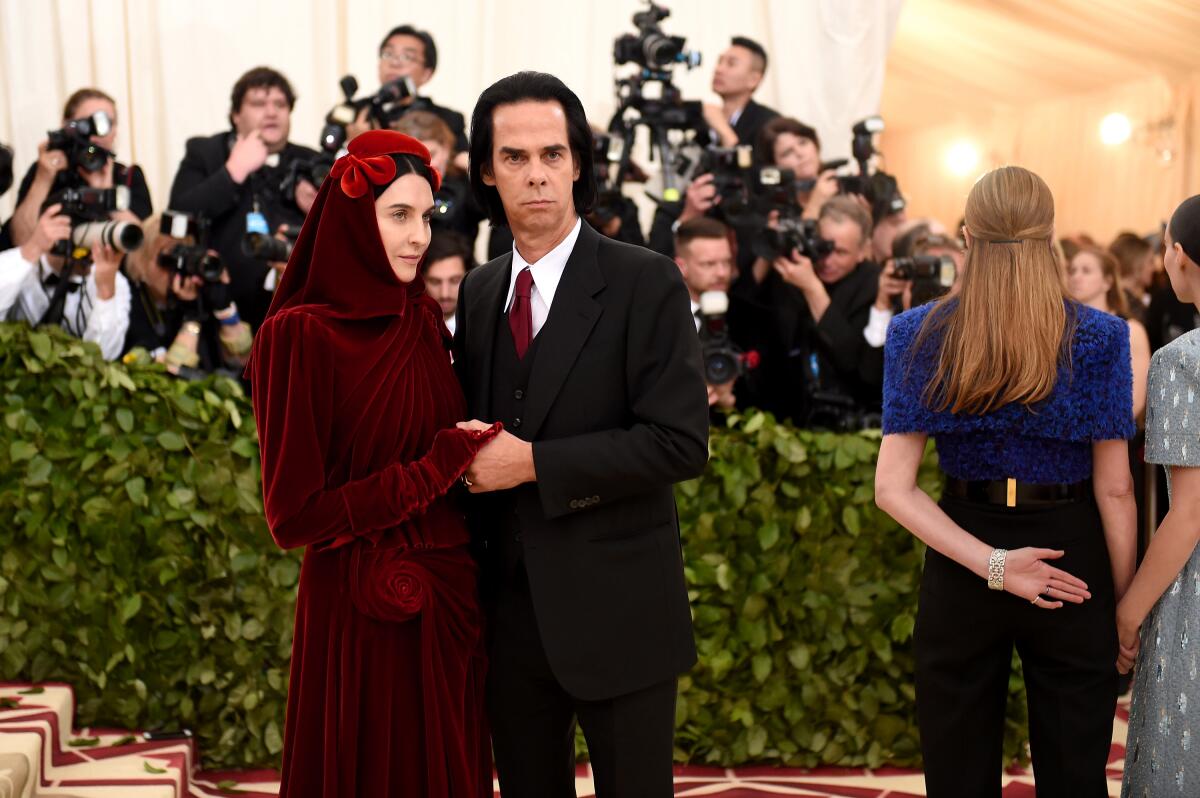

Susie Bick and Nick Cave at the Met Gala in New York in 2018.

(Jason Kempin/Getty Images)

At the end of “Frogs,” the narrator describes meeting Kris Kristofferson on a Sunday morning, which is obviously reminiscent of their “Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down.”

It is one of the great songs about spiritual disillusionment. “Frogs” is framed by examples of spiritual collapse, with the murder of Cain and Abel at the beginning and Kristofferson’s song at the end.

I guess you've loved “Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down” for decades.

Yes, I listened to a lot of country music as a kid growing up in Australia. It’s funny, I had no idea what was going on in the rest of the world, but from the age of 10 or so I would sit and watch “The Johnny Cash Show,” which was on Australian television on Saturdays. He was one of the musicians that I became attached to in that obsessive way that you get when you’re young, because I saw him as some kind of outlaw, some kind of villain.

Cash made a great “Sunday Mornin'.” Willie Nelson did too.

Willie has an extraordinary voice, he can make any song his own. There is an incredible version of Coldplay's “The Scientist” that is the most beautiful thing you've ever heard.

The lyrics sheet for the new album specifies that “Oh Wow Oh Wow (How wonderful she is)” is for Anita Lane, the first member of Bad Seeds to pass away in 2021. Did you set out to write a song about her?

No, I don't think so. I came across some lines and there was a joy in it all that reminded me of Anita, so I wrote about that. As I was writing on the piano, my wife walked past me: “Oh, what a beautiful song. Who's it by?” And I said, “It's not you this time, darling.” In the Melbourne art and music scene, Anita was this bright, glowing, flaming, laughing creature that us dark, drug-addled men surrounded ourselves around. That's what I wanted to capture in some way: the simple joy of what it was like to be in Anita's orbit.

The first verses say: “She pulls up by the front of her panties / I can confirm that God really exists.”

Not bad.

Would Anita have appreciated those images?

She would have liked it, but, look, everyone likes to have a song written about them. I once wrote a song called “Scum” about a journalist, a terribly personal song about his private life and everything else. He claims to this day that it is his favorite song.

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds perform at Coachella in Indio in 2013.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

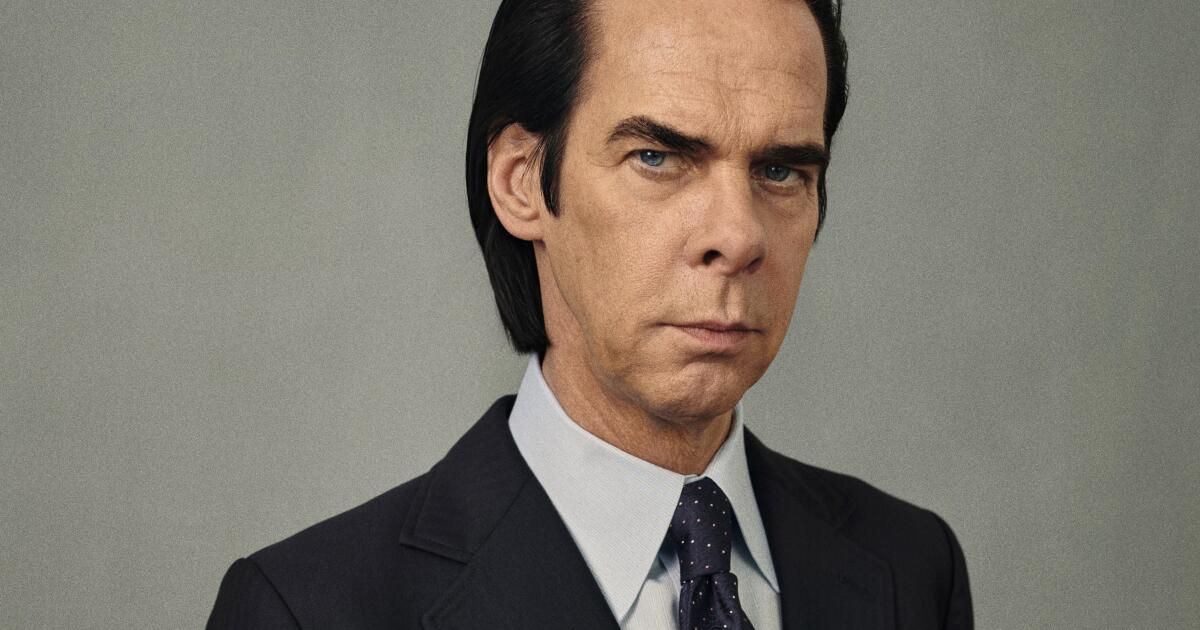

How important do you think your appearance is to your art? Would it work the same way?

What if I was a fat, bald guy in shorts? I don't know. I'm not going to name anyone, that would be cruel, but there are so many people like that, it's amazing.

Okay, but what does sex appeal bring to you as an artist?

Are you trying to say that if I wasn't tall and thin and had some hair, I wouldn't be able to do some of the things I do? That it's a form of privilege? I don't really feel that way. I have all sorts of weird neuroses about my appearance.

Is that true?

Ask my wife about this.

What's the funniest song you've ever written?

It’s a difficult question, not because there aren’t nearly any, but because there are so many. It’s one of the most disconcerting things: like Leonard Cohen, my songs come across as depressive when many of them are explicitly written as comedy songs. I don’t know if “No P— Blues” is the funniest song I’ve ever written, but it’s pretty funny.

You've talked about how much it meant to you that Johnny Cash covered “The Mercy SeatHave you thought about who else you would love to hear sing one of your songs?

A lot of people cover my songs, and some of them touch my heart because those were the people I listened to when I was a kid. So for Johnny Cash to do it, and for me to meet him and sing with him, that was a gift that no one can take away from me. But I don't sit there thinking, “I hope Taylor Swift covers my song.” Although, well, I wouldn't mind. I've just put it out into the universe. Maybe it will manifest itself in some way.