Here we go again.

In Hollywood's continued sad attempts to question the joy of music by downsizing stellar classical musicians, “Maria” joins the brief parade of “Tár” and “Maestro.” Maria Callas's new biopic follows the takedowns of fictional director Lydia Tár and giant Leonard Bernstein with a dramatization of the most compelling singer I've ever met: live, recorded, on video anywhere. (I'm not alone in this estimate.) All three films have this in common: over-the-top musicians are tragically brought down by their own arrogance and become monstrous. Everyone is a victim of their celebrity, something celebrity-breeding Hollywood turns out to be pretty good at.

“Maria,” which began streaming on Netflix this week, focuses on Callas’s final lonely years, when she was, if you want to believe this narrative, pitifully self-destructive. She had lost her voice and her lover, and had nothing to live for. He could not recover the mythical La Callas or make peace with the woman, María. It is an ignominious tale of woe and quixotic temper.

The somber film begins and ends with Callas' solitary death. In typical flashback style, we witness his decline and delusions as he attempts to regain his voice, the attentions of Aristotle Onassis, and the adoration of the public. Flashbacks are mixed with fragments of documentary footage, giving glimpses of some notable moments in his life.

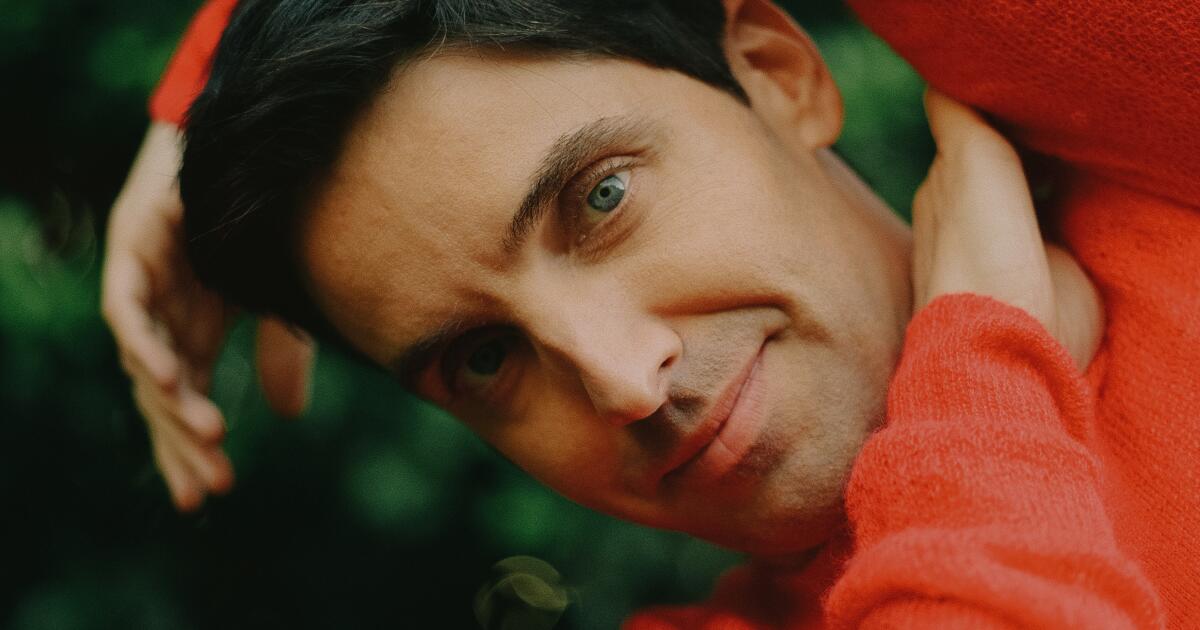

Throughout, the unlikely Angelina Jolie captures Callas' style in her dress, public demeanor, and movements. She perfectly shows off sensational hairstyles from the 50s and 60s. She would make a great plastic Callas doll.

The real Callas impressed in another way. Her face did not have Jolie's spectacularly exact proportions. In fact, Callas became what she considered an ugly duckling. When she first appeared on stage in the late 1940s, she immediately demonstrated a voice to be reckoned with and fervent vocal theatricality. But she was a large woman and was said to be somewhat awkward on stage. Director Franco Zeffirelli described her as big in every way (big eyes, big nose, big mouth, big body) and compared her to the Statue of Liberty.

Watching the 1953 film “Roman Holiday” made Callas decide to look like its diminutive star, Audrey Hepburn. Callas lost 80 pounds in a single year. He had already worked with great directors, especially Luchino Visconti, but now he had the physical means to go much further and invent the modern concept of opera as drama. His voice had lost some of its shine, and those who didn't like him blamed weight loss, which wasn't the case. It was, rather, his compulsion to throw his entire being into furious theatrical intensity.

On the surface, Callas had become an icon of elegance, but now she could make her big eyes, big mouth, and big voice penetrate like nothing anyone in opera had ever experienced. She transformed not only herself but also the art form.

Callas's career in opera lasted less than two decades, ending in 1965. She was only 42 years old when she sang her last opera performance on stage, a production of “Tosca” at Covent Garden in London. People came up with all kinds of reasons why his voice faded so early. Only after his death, 12 years later, did we learn that he suffered from dermatomyositis, which causes muscle weakness that can affect the vocal cords and which also likely caused his heart failure at age 53.

Jolie's voice has been lightly mixed with Callas's in such a way that it slightly sanitizes Callas's. Joile's voice sounds almost like Callas's but without the touch of Callas's New York accent. He is missing, above all, Callas's charming smile. None of this might matter as much if director Pablo Larraín had focused less on delivering glamorous shots of Jolie.

The movie is called “Maria” for a reason. Callas's life was, in fact, a life of conflict between the artist who grandly became La Callas and the woman who was Maria. But it is necessary to understand both. No doubt he stopped singing due to his physical condition. Still, his greatness gave him a remarkable ability to transcend biology. However, her need to become the woman she wanted to be fueled her ultimately toxic obsession with Onassis.

I saw how exceptional the transcendent part of this complex equation could be on his ill-fated 1974 comeback tour with tenor Giuseppe di Stefano. As a graduate student at the time, I had a seat in the upper balcony of the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco. The acoustics are better there and I bought some binoculars just to see it.

It sounded pretty bad. The voice had disappeared. But not the intensity, not the presence. In fact, this became one of the best songs I have ever known. She seemed at the same time superhuman and super-suffering. It is not possible to experience the magic of Callas and the music becoming one in the horrible underground recordings of the concert found on YouTube and elsewhere.

Better to watch Pier Paolo Pasolini's 1969 film “Medea,” in which Callas stars in a purely acting role. Like Larraín with Jolie, Pasolini was fascinated by Callas's face, particularly her nose. He scrutinizes its expressiveness, its extraordinary power. He no longer needs opera, he has it inside him. Pasolini uses music as if he were filming a Noh play but without masks. The fact that this film receives so little regard in the opera world and even among Callas fans shows that, if you pay enough attention, it remains ahead of its time.

His radical sophistication and bravery became more evident in 1974 when he spoke at a Verdi musicology conference in Chicago. She seemed dignified, eloquent, unsentimental and downright revolutionary. He had no need to waste time with musicologists and their talks about forgotten early Verdi masterpieces. Knowing what mattered and what didn't, he suggested they take the best parts of those operas and make something modern and meaningful. He also blamed Puccini for making the singers and the audience lazy, because he was not challenging enough.

A year later, Onassis died, which is said to have caused Callas to lose interest in life. He had left Callas, whom he never married, to marry Jacqueline Kennedy, but the flame burned in Callas until the end. Her last two years were obviously very difficult, with drugs, depression and dermatomyositis, all of which seem in bad taste in “Maria.” I wonder if she became a recluse in part because patients with dermatomyositis are supposed to stay out of sunlight. His body was failing him.

A more affectionate and fanciful portrait of Callas in those years is the basis of Zeffirelli's 2002 biopic, “Callas Forever,” starring Fanny Ardant and Jeremy Irons as her agent. Zeffirelli had worked with Callas and knew her well. To better understand Callas, check out Tony Palmer's 2007 documentary, “Callas,” in which Zeffirelli is particularly illuminating.

All the adoration, the glamor and the good life were, for Callas, a determined life of bread and roses. Rather, his art had always been the way he boldly filled that void with incredible meaning. “Maria,” on the other hand, offers little more than pathos and posturing.