A masked killer trudges through the woods, like Jason Voorhees, but instead of jumping out at us as a surprise, we remain permanently at his side, a companion in his lonely, bloody quest for revenge. A decomposing zombie boy returns home to his grieving mother and his religious grandfather, but instead of screaming in terror, his family tenderly cares for him.

A pair of new horror films premiering in Los Angeles over the next two weeks cleverly disrupt the tried-and-true forms of their respective subgenres.

Told from the killer's point of view, Canadian filmmaker Chris Nash's debut feature, “In a Violent Nature,” is a horror film that patiently follows a mute, burly revenant named Johnny (Ry Barrett) from one death to the next. , as if a first-person shooter game. Although it includes some gruesome themes, Nash intentionally avoids a traditional catharsis.

The other, “Handling the Undead” by Norwegian director Thea Hvistendahl, is a sad and melancholic version of the zombie movie starring Renate Reinsve and Anders Danielsen Lie of “The Worst Person in the World.” Here, the stunned undead don't haunt people's brains or infect anyone else with a virus. They simply return to their loved ones, confused. Grief-stricken, the living care for these sentient corpses, hoping to find signs of who they once were.

“It's much less of a roller coaster and more of a tour bus,” Nash, 42, says in a video call about “In a Violent Nature.” Similarly, “Handling the Undead” has a meditative tone. Hvistendahl, 35, refers to it over Zoom as “a drama with a horror premise” and “a melancholic horror.”

Both exude a modest joy. And looking at their film backgrounds, neither explains the thoughtful concepts that have emerged in their trailers, which premiered at this year's Sundance Film Festival in January.

Nash grew up loving VHS covers for horror titles and reading Fangoria magazine while dabbling in amateur makeup effects. Hvistendahl, for his part, didn't imagine a path of horror until he directed the 2019 short film “Children of Satan,” actually about two girls at a Christian summer camp.

“So I set out to make a poetic thriller and when I finished it, people called it horror,” Hvistendahl says. “It was when I was making that film that I discovered that I really enjoyed using the genre in my films.”

Nash cites some unusual influences for a midnight filmmaker, primarily Gus Van Sant's methodical early-2000s “death trilogy” — “Gerry,” “Elephant” and “Last Days” — respectively, about a couple of friends lost in a desert; a school shooting inspired by the Columbine incident; and the suicide of Kurt Cobain. These films address difficult topics with marked pragmatism.

In all of them, the camera hovers behind the characters, an apparently objective witness. Nash believes that in doing so, Van Sant relinquishes ownership of the narratives, opening them up to interpretation.

“I liked the fact that I never felt pressured by him as a filmmaker,” Nash says. “I felt like the characters carried me.”

Renate Reinsve in the movie “Handling the Undead.”

(Pål Ulvik Rokseth)

The concept of a wilderness slasher was the ideal format for Nash to replicate that formula, offering long periods of silence.

“It has a slight documentary feel to it that tricks you into feeling like there's some authenticity to what you're seeing, even if it's a zombie monster walking through the woods,” he says.

For Hvistendahl, his main source of inspiration was a book, “Handling the Undead,” the 2005 Swedish novel by John Ajvide Lindqvist, best known for writing the vampire drama “Let the Right One In.”

The uniqueness of Lindqvist's universe (somehow both grounded and otherworldly) inspired the filmmaker to make “Sons of Satan,” and when the rights to “Handling the Undead” became available, she jumped at it.

“What I really enjoy about a lot of his work,” says the director, “is how, instead of treating it as something purely supernatural, it's treated a little more like magical realism.”

Hvistendahl inherited a script from the author and rewrote it, keeping its grim essence but removing most of the bureaucratic elements that detail how the government literally manages the undead by isolating them in a housing complex.

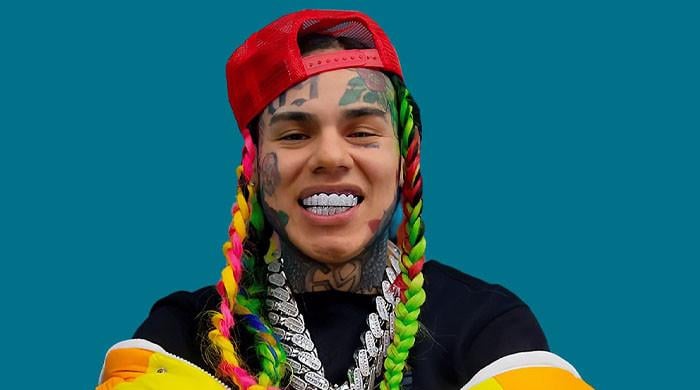

Director Chris Nash, wearing a cap, on the set of “In a Violent Nature.”

(IFC Movies / Shudder)

To break the rules of their cinematic predecessors, both Nash and Hvistendahl devised new parameters to follow in the realization of their projects.

In direct defiance of so many slashers of the past (since John Carpenter's “Halloween”), Nash opted not to include a score and instead let the ambient sounds take their place. Additionally, he tried to include Johnny in every shot, whether it was just his hand, a foot, or an article of clothing.

“It was important that Johnny's presence be felt in every frame until the crucial moment of the climax,” explains Nash.

From Hvistendahl's perspective, his most overwhelming concern was avoiding humor, despite the example of “Shaun of the Dead” and so many successful zom comedies. While researching, he realized that zombies could cause laughter when they attacked or moved quickly, something you can't do.

“For the atmosphere I wanted to create, where we have to care for the undead and understand what the living feel about them, I thought that making them funny would be taking the movie to a different place,” says Hvistendahl, also explaining his reason for removing the moderate use of zombie dialogue in the novel. “It would have been difficult to get them to talk without making them stupid.”

Director Thea Hvistendahl, center, on the set of “Handling the Undead.”

(Morten Brun)

Another challenge for Hvistendahl was finding the right look for the undead. The intention was to make them appear not to be alive while still conveying a sense of the person they used to be.

“We do a lot of research on the dead and what they look like when they start to rot,” he adds. “But those details are also very difficult to find because no one has actually unearthed a two-week-old body.”

Concerned about the physical appearance of her undead, Hvistendahl worked with a movement coach who developed theories about bodily separation in the afterlife. Now, back in their mortal bodies, the zombies would move differently as they were used to walking through weightless walls.

Inconsistent on-screen movement was one of the key reasons Nash decided to reshoot his film from scratch after completing nearly 80% of principal photography during fall 2021 in Sault Ste. Marie. Marie, Canada, the director's hometown, eight hours northwest of Toronto.

During the first week of filming, Nash had to recast the actor playing Johnny after the original actor suffered an unexpected medical problem. Upon receiving the cut, the director noticed the subtle difference between the two actors he used to play the monster.

“With a character who doesn't speak, it's all about how he moves, so you notice all the little differences between the two performances,” says Nash. “It became very clear that, 'Oh, this is not the same person.'”

Modestly, Nash ultimately attributes his change to a lack of confidence and communication skills after working primarily in special effects and makeup for several years. “The real reason it had to be shot twice was because it had been too long since he had directed any fictional narrative,” she admits. “I got too rusty at being able to convey how I wanted something to be portrayed.”

In the end, the two films seem like formal bets that manage to unbalance the viewer. For Nash, his contemplative approach to “In a Violent Nature” gives the audience space to carefully consider what they are looking at and why the artist would want to point their gaze there.

Hvistendahl was interested in articulating the human desire to preserve those we love even after they are gone. Horror served as a vehicle to create a singular metaphor out of tropes that most are familiar with.

“Death is the one thing we, as human beings, have yet to fully understand,” he says. “It's very hard for the brain to understand that they're not coming back.”

Both filmmakers expect polarized reactions from audiences for their unconventional horror outings.

Hvistendahl knows that his is a difficult sale. “If I tell some people it's a horror movie, they'll say, 'I don't want to see that,'” he says. “For others, if I say it's horror, they expect more blood or scares.”

Nash believes there will be two audiences for “In a Violent Nature.” The first is the one who knows the genre deeply, made up of those who will appreciate the story adopting the killer's point of view for a change.

“There will also be an audience that expects a very simple clone of 'Friday the 13th,'” Nash says. “And I could see them either pleasantly surprised or incredibly disappointed with the speed at which my film is developing. Hopefully everyone will give it a chance and like or dislike the movie it is and not the movie it isn't.”

And no matter where you fall on that spectrum, you can't blame him for trying something different.

“Gender is an open playground,” Nash notes. “It is the only area of culture where there are no strict rules. You can make a genre film that doesn't have any scares, but it's still a genre film and I find that immensely interesting.”

Although he doesn't talk about his own film. “In a Violent Nature” is not free of scares, nor is “Handling the Undead.” But both call into question the way we've been conditioned to expect our shocks.

Watching them, we must surrender to their uniquely unnerving pace – as good a definition of horror as any.