On the shelf

Rompecorazones

By Mike Campbell

Grand Central Publishing: 464 pages, $ 32

If you buy linked books on our site, the Times can obtain a commission of Bookshop.orgwhose rates support independent libraries.

In his new memoirs, “Heartbreaker”, Mike Campbell remembers an afternoon in the early 1970s when Tom Petty, a bandmate in Campbell on a cover band by Gainesville, Florida, called Mudcrutch, played one of his songs. While Petty laughed the chords of his future basic element of FM radio “Don't Do Me Like That,” Campbell told Petty: “I would give my right arm if I could write such a song.”

Campbell at that time was a talented guitarist raised by a single mother, desperately trying to get up from poverty by becoming a professional. When he met Petty, he was working horrible minimum wage jobs and seriously thinking about enlisting the army. “I wanted to play the guitar to avoid a real job or join the Air Force,” says Campbell. “While anyone would pay me money to play, that's what I was going to do.” Campbell also wrote songs: they were good, not great. Petty, in contrast, wrote well and quickly. Years before either of them knew the heartbreak, Campbell decided to work hard and work intelligent: Petty was an outstanding talent, and Campbell would follow the course with him.

Campbell became one of the best rock companions: the man to the left of Petty on stage throughout the career of more than 40 years of the Heartbreaker race, until his last show in the Hollywood Bowl on September 25, 2017, a week before Petty's death at 66 years. It was a role that spent years cultivating.

(Grand Central Publishing)

“Heartbreaker” is a story of resistance and rewarded patience. In a short time, Petty became, well, Tom Petty and Campbell became a guitar god. A teacher from the perfect guitar, the solos of Campbell are tattooed in our brains as indelibly as Petty's playful growl. They worked so well together that when Petty made solo albums outside the band, he enlisted Campbell to write, produce and play. “You cross someone and win a left turn or the right, and you can define your whole life,” says Campbell from his home in Woodland Hills. “If I had not met Tom, or if I had resigned early when things became difficult, I don't know where my life would have gone.”

Things were difficult for years when the musicians entered and left Mudcrutch, and the band put the hard miles, playing hundreds of bar concerts throughout the south, looking for adequate alchemy that would distinguish it from any other excellent cover band in Florida. There was a cavernous Gainesville bar named Dub's, and the group played there every night for weeks, occasionally launching one of Petty's Chiming and Inflectted Byrds originals. “At that time,” writes Campbell, “everyone tried to sound like the Allman brothers. No one was playing … short songs with sweet harmonies and big choirs.”

The band played for drunk and angry cyclists, accompanied the contest of wet t -shirts, participating in shout matches with the greedy club owners. Some frustrated band members left; Campbell knew better. He knew Petty was his golden ticket. “We were young and we had a dream,” says Campbell. “We weren't really convinced that we would get anywhere, but we dream of it.”

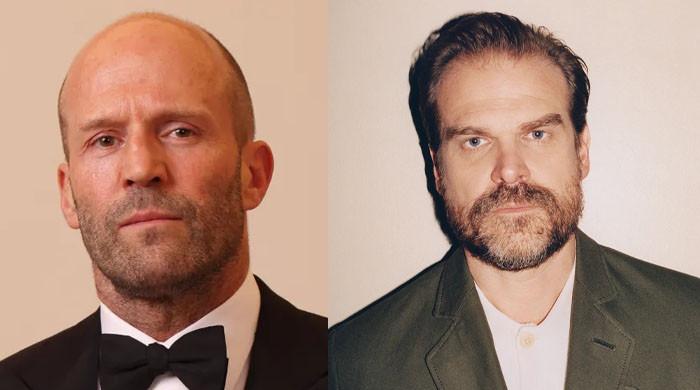

“I was never going to compete with him for leadership,” says Mike Campbell about Tom Petty, “but it could be the guy who fills the gaps.” I could drive it and do better. “

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

According to Campbell, Petty, only 19 at that time, arrived completely formed. Bantoso, self -confident and full of ideas, Petty always thought five movements ahead of all others in the band. “I had the ambition and impulse to do something great and not be diverted or settle for less,” says Campbell. “But in many ways, we were very the same, especially in terms of the music we love.” It was Petty who called at the doors of the record label with a demonstration tape in his pocket, until the president of Shelter Records, Denny Cordell, discovered it and released the band. “I was never going to compete with him for leadership,” says Campbell, “but it could be the guy who fills the gaps.” I could drive it and do better. “

Perhaps more than anything, “Heartbreaker” is a manual on how to work effectively in a band with an alpha male. Campbell learned to become a conciliator and a mediator: how to let trivial complaints die, to soften things for the greatest good, not to let greed get in the path of the overview. Petty could be volatile and erratic, I knew it was the straw that stirred the drink, but always encouraged Campbell to write.

“Tom was very confident,” says Campbell. “I had his own songs, so I followed him and contributed the best I could.” Instead of feeding his songs in the group, Campbell would gently push Petty with a cassette cassette of skeletal chords or a chorus or a choir with the hope that Petty can smell a song. This method of collaboration would produce classics, but not without some concern on the part of Campbell.

“At first, I wasn't sure of my writing,” says Cambpell. “I like to perfect my writing before showing it to anyone, even my wife. There were times when Tom took a long time before listening to my things, but then something incredible occurred to him. I prefer that you feel in the eyeball with someone in a room … “

Petty and the Heartbreaker exploded in 1976 when their homonymous debut album threw the hymns “American Girl” and “Breakdown”, but as the bets increased, the internal and external pressures did so. Campbell made its best level to make sure the coldest heads prevailed, that the band did not collapse under the weight of expectations.

Mike Campbell, on the left, and Tom Petty of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers act in the old Waldorf nightclub in San Francisco in 1977.

(Richard McCaffrey / Getty Images)

“Damn The torpedodedos” of 1979 was the first of his mega-sale albums, but almost broke the band. As Campbell remembers in his memoirs, producer Jimmy Iovine and his engineer Shelly Yakus pushed everyone so strong in the study that he began to feel like a psychological war. Heartbreaker drummer Stan Lynch took the worst part of torture; On numerous occasions, Lynch left the studio, just to be shaken when no one else worked (Lynch left the band in 1994).

Campbell remembers having touched at least 70 “refugee” shots, a song that began his life as a Campbell riff before Iovine, Yakus and Petty signed it. “It was not easy because Tom was very direct and did not suffer fools, and practically told him the truth,” says Campbell. “There was a lot of pressure to be great.”

There was also the issue of money. At first, the first manager of The Heartbreaker, Elliot Roberts, presented it in unequivocal terms: Petty would receive 50% of the profits and the band would divide the other half. This arrangement, according to Campbell, created Ill for years with benchmark Benmont Tench. At one point during the “Torpedo” sessions, Campbell and Petty exchanged words about Campbell wanting a bigger cut for their work, to which Petty pronounced three words: “I'm Tom Petty.” End of the discussion.

“To be fair, Tom gave me a great cut in 'Full Moon Fever',” says Campbell in reference to Petty's multipurpose album 1989. “There was also a generous side for him.”

More importantly, Petty and Campbell would co -write songs that millions of people now know by heart: “You Got Gotes”, “Refugee”, “Here comes my girl”. While Petty accepted more Campbell's songs, Campbell's confidence as composer flourished, and branched beyond the band, co-writing with Don Henley the megahits “The Boys of Summer” and “The Heart of the Matter”. “Tom made me believe in myself,” says Campbell. “We could always talk about things and return to love and respect. That's why we stayed together for so long. “

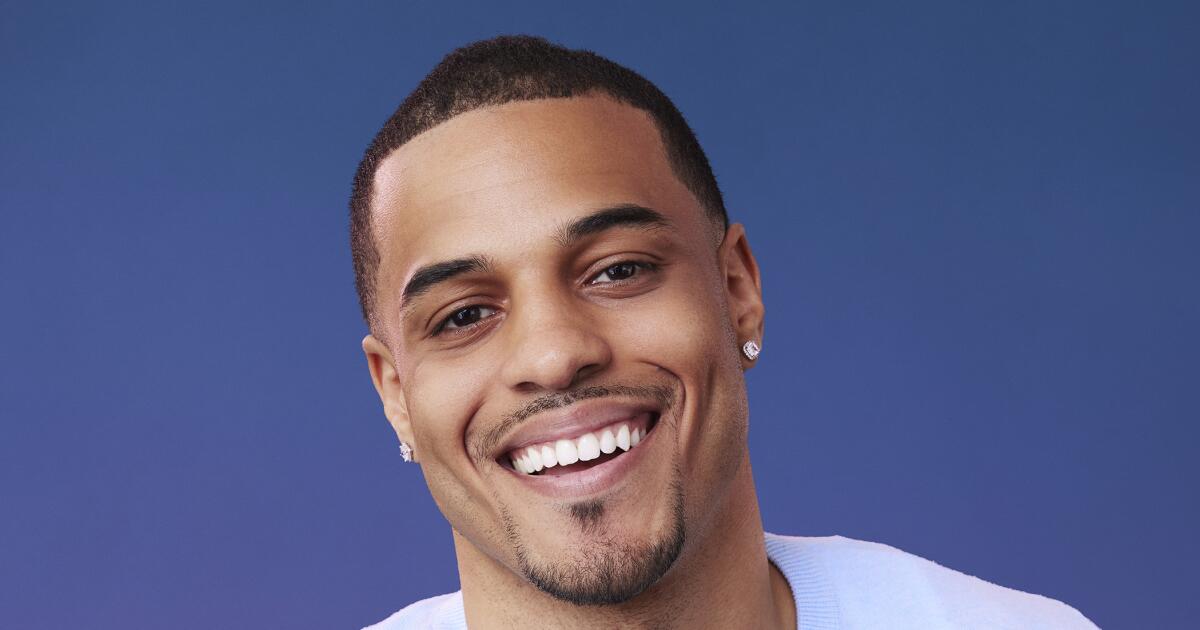

Mike Campbell at home at Woodland Hills.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)