To hear him describe it, eyes alight and arms blocking imaginary space, British filmmaker Jonathan Glazer has a happy place: his small post-production studio in Camden, London. “It's actually like a laboratory,” he says, “just a room, but this size, a little bigger. Double the height. “There’s a little mezzanine up there, with a screen on the wall.”

Glazer then introduces her collaborators, a dream team: “Mica writes, Paul cuts, I make the tea,” she continues, referring to Mica Levi, the inspired, once-in-a-generation songwriter with whom Glazer first worked. on 2013's “Under the Skin,” and Paul Watts, his longtime editor dating back to his videos with Massive Attack and Dead Weather. “We move and one person informs the other.”

Meanwhile, sound designer Johnnie Burn, also of “Nope” and “Poor Things,” is on video all day from Brighton, sharing ideas and trying out remixes as he goes. Watts is eating a sandwich. “It's all very similar to that,” Glazer says. “And I think the fact that we're together in space is how we got to where we got, because we're all in conversation with each other and with the movie.”

Paradoxically, the film that emerged from this happy arrangement is “The Zone of Interest” (in theaters), Glazer's radical and disturbing reinvention of the Holocaust drama set just beyond the wall of the Auschwitz camp, where somehow the family of a Nazi commander intends to enjoy his private garden. As creatively nourishing as Glazer's setup may seem, making the film was not easy, a process compounded by the director's Kubrickian penchant for preparation and perfection. He spent a combined total of 19 years on his last two feature films, two of them just in the post-production of “Zone.”

A scene from the movie “The Zone of Interest”.

(A24)

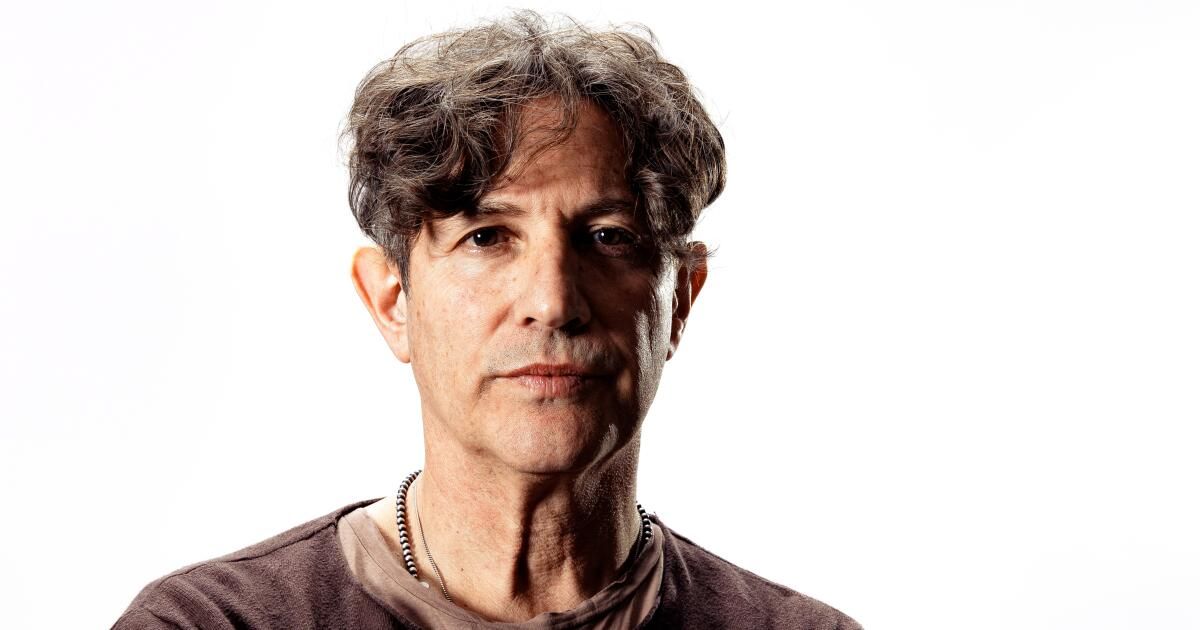

“I'm not one to call an agent and say, 'What scripts are out there?' Send me something good,'” Glazer, 58, tells me. We're talking in a closed-door conference room that I've tried to make as un-Hollywood as possible, turning on the lights and ordering some black coffee. It's a crisp morning in Los Angeles and her cozy brown sweater makes sense. “It's just not the world I'm in. It's more like something that happens inside me, forcing me to follow a certain path.”

Glazer's work on the film began in earnest in 2014, when he first read the recently published novel “The Zone of Interest” by the late Martin Amis, a fictional account set in Auschwitz that the filmmaker would eventually re-investigate for years and discard. most of it. of, including the central love triangle of it. But even before that, Glazer had been thinking about making a film about the Holocaust; always, he knew, from the point of view of the perpetrators, not the victims.

Was turning 50 the spark that inspired your turn toward mortality? “On me she never seems to be so conscious,” she objects about her choice of projects. “I just think there are things you come to at different times in your life. You're examining different things at different stages, aren't you? With the experiences you have had.”

He remembers growing up in suburban Hadley Wood in the 1970s and attending a Jewish public school during a time he describes as “pretty unreconstructed.”

“Kids would stream out the school doors to get on buses and trains to go home at the end of the day,” Glazer recalls, “and you would stuff your blazers and ties in your bag so you wouldn't have anything to do.” . school colors to identify you. And you would keep your head down, actually, until you got home.”

It didn't always work, he remembers, dodging the non-Jewish thugs on the road. “The fact that it was a Jewish school gave them ammunition for a bit of conflict, which happened,” he adds grimly.

Glazer admits to the idea that what led him to make “The Hot Spot” was a sense of responsibility to address his memories of anti-Semitism. “I hadn't thought about it in those terms,” he says, “but yeah, I think there's probably a part of me that felt the need to point my skills, whatever they may be, at that topic to see whether or not I could contribute to it. I think it is a human responsibility, rather than a tribal one.”

Three years of research into Amis's own sources led him to the real-life camp commander, Rudolf Höss, whose mentions in the Auschwitz records were excavated by Glazer's researchers. There was also Piotr Setkiewicz's important 2014 study “The Private Life of the SS in Auschwitz” and its volumes of testimonies, many of them from Polish teenagers who worked in the Höss home and on the grounds.

“That really caught my attention,” Glazer says. “The horror was in the house. Anyway, fascism starts in the family, so there was something ordinary and familiar about that vulgarity. “It was absolutely captivating.”

Christian Friedel in the film “The Zone of Interest”.

(A24)

What Glazer discovered in Bedrock were not the monsters of Hollywood Holocaust movies, but social climbers seeking to improve their status. “What they expected for themselves and their petit-bourgeois dreams is not so different from ours,” he says. It wasn't sympathy he sought, but clarity.

The filmmaker's investigation took him through the gates of hell, where he remembers making a devastating realization. In the Auschwitz archive there was a single roll of film, probably taken by Höss himself, of parties and children.

“And this is a happy family in a backyard getting on with their lives,” he says of the shots. “There is no evidence in this roll of film that the camp wall was actually the garden wall. She didn't shoot him. So that tells you a lot.”

Moments like these, by Glazer's own admission, led him to almost abandon “Zone” as he considered it harmful to his mental health. “It's just too much darkness, too much weight, too much responsibility,” he recalls. “And you start questioning your motives and it's a shitty place to find yourself. And I remember my wife saying to me, 'But your job is to turn that camera around and photograph that wall that they didn't photograph.' That's exactly what you're doing there.'”

He also remembers being on the side of the camp, facing the wall opposite the one where the Höss structure still stands. “You would have heard the kids splashing around in the pool,” Glazer says. “It is compartmentalization manifested. “I knew that wall was the center of the entire project.”

Carrying the weight of the situation without resorting to feeling became the toughest test of Glazer's career. He ended up filming the film himself in an adjacent house on the Auschwitz perimeter, with the camp's towers in view. The cameras and microphones would be hidden from the cast to get as close to reality as possible.

“I didn't want to get caught up in the film psychology of an actor,” Glazer says. “I felt like I needed to film this somehow as if I were filming real people. I needed to believe they were the people they were portraying before anyone else could believe.”

Sandra Hüller in the film “The Zone of Interest”.

(A24)

Those are tough questions for any actor. Sandra Hüller, so electrifying in “Toni Erdmann” and this year's courtroom thriller “Anatomy of a Fall,” needed, by Glazer's estimate, a year of persuasion before committing to the role of Höss's wife, Hedwig. . “I think my doubts made her feel more comfortable than my certainties,” says the director. “But I knew I had to have her for that role.”

Whatever Hüller was fighting for, it was surely as difficult as what was asked of Christian Friedel, chosen to play Höss himself.

“I didn't want Christian pretend vomit; “He wanted me to throw up and I couldn't,” Glazer recalls, smiling shyly at the harsh request he made of her during the filming of one of the most nightmarish scenes in “Zone.” (The comparisons to Kubrick are not unearned.) Ultimately, the actor and director studied a notorious scene from Joshua Oppenheimer's 2012 documentary, “The Act of Killing,” in which an Indonesian mass murderer vomits in near-riot with his own mind. “There's always a way around it,” says Glazer, leaving the technical details a mystery.

His first feature film, 2000's “Sexy Beast,” was a brutally funny film about British gangsters, impacted by comic moments of dreamlike surrealism. “Birth,” starring Nicole Kidman as a Manhattan widow who begins to suspect that a young man is actually her dead husband reincarnated, was also hers. “Under the Skin” is about aliens. Glazer's dogged pursuit of realism at all costs seems new to him and speaks to the seriousness of his rigor. He doesn't pretend it was easy.

“I needed light there,” he remembers about the most difficult moments when doing his last job. “I needed light in me to move forward. I needed something holy.”

A salvation of sorts came in one of Glazer's interviews during her preparation period: a 90-year-old Polish woman who as a child secretly rode her bicycle in the middle of the night, leaving food for prisoners.

“When I met her, I really felt like I had met this angel,” Glazer says. “I had seen that there was light there too. There was that other thing that is in us as human beings.”

An image from the movie “The Zone of Interest”.

(A24)

He includes these episodes in the film, shot with black-and-white thermal photography, almost like an X-ray world, punctuated by some of composer Levi's most disturbing noises, like belches from hell. It's hard to imagine the film without these night flights. “It's literally the opposite of everything we've seen in the movie,” Glazer says.

Since last May's Cannes Film Festival, where “The Zone of Interest” won the Grand Prix (an award second only to the Palme d'Or), Glazer has relaxed a bit, although he admits to being surprised (and moved) by the enthusiastic reaction. received in France. Strangers approached him, shocked, not even with questions but simply wanting to be heard.

“There was something cathartic about it that they wanted to share,” he recalls. “And it was at that moment, just people on the street, young and old, that it really hit me that I thought, Oh my God, there could be something happening here that's outside of the movie.”

Glazer pauses, a wave of humility bringing back all the questions that troubled him from the beginning a decade ago. “Am I doing this because I want to make a film about the Holocaust?” he asks. “Why am I here? Why am I doing this? Why me? Who do I think I am to take this on? I have those doubts all the time. I lose a lot of sleep over this, and I still do.”

His next film, he tells me, will be about “tenderness, how tender we can be too.” It won't arrive for a while. Meanwhile, there's the position Glazer now finds himself in, premiering his most celebrated effort in a revitalized awards season, with the broader implications of making a film about violent political dissociation available to anyone who wants it. .

“Of course it speaks to this moment,” Glazer says. “Of course it does. But it's about who we are as a species and what we're capable of. I think there's some alarm in the movie. It was certainly made with that intention. We're trying to sound a warning.”