Kieran Culkin tells a story about his desperate desire to go to Poland to make Jesse Eisenberg's road movie, “A Real Pain,” and although every word is true and comes from a deep place in his soul, it is tied to love. how he feels about his wife and children, it still feels like a bit of salesmanship in the film.

“The bottom line is that this movie was so absolutely perfect that I couldn't say no to it,” I tell Culkin, paraphrasing his speech. “If it had even a small imperfection, I would have abandoned it. But not. “It was impeccable.”

“It's honestly the truth and it was disappointing for my wife,” Culkin says. “You should have seen his face fall when I said, 'I'm going to go into the other room and read it again.' And this time I'm going to read it with the perspective of really trying to find holes and really trying to find a reason to say, 'Actually, this isn't as good as I thought.'

“Apparently she was hearing me laughing from the other room and said, 'Oh shit, this isn't going so well,'” Culkin continues. “She didn't want to take this trip either. And when I walked into the room, I just said, 'I'm sorry, honey.'”

Eisenberg, the writer, director and co-star of “A Real Pain,” is seated next to Culkin. In the film, they play cousins who travel to Poland to visit the childhood home of their beloved late grandmother, a Holocaust survivor. Eisenberg presents himself as the introvert and Culkin as the charmer whose exuberance masks deep inner turmoil.

“Ninety-seven percent of Screen Actors Guild actors aren't working,” Eisenberg tells Culkin, “and you're like, 'Sorry, honey.' I have to make a movie in which I star.'”

Did you have any idea I was hesitating?

“What I was doing while he was doing that was making plans, buying costumes, determining and confirming locations and sets,” Eisenberg continues. “To say we were immersed in production is an understatement. Two weeks before a movie shoot, you're shooting the movie. Everything is in its place. “Every dollar has been spent.”

“Yeah, I wasn't really aware of how far along you were,” Culkin says, sheepishly. “I didn't know you were there until I had that conversation with Emma.” Emma is Emma Stone, one of the producers of “A Real Pain,” and the adult in the room who was responsible for convincing Culkin to get off the cliff and get on a plane to Poland.

“Does it change your perspective about maybe signing things that you're ambivalent about?” Eisenberg asks.

“Yeah, it scares me to death now,” Culkin responds. “I've always been terrified of saying yes to something because what happens if they actually say, 'Okay?' Let's do it right now.' Doesn't that scare you at all? “It’s like asking what you want for dinner on a Thursday in March.”

“For me,” Eisenberg responds, “that gives me the peace of mind of having a structure and knowing that something is coming.”

As you can see, Eisenberg and Culkin bring different sensibilities to the disparate characters they play in the film, cousins who were once close but have grown apart. But the two Hollywood veterans, who began acting as children, are also alike in many ways: intelligent, self-described misanthropes who care deeply about their craft and respect others.

All those shots that Eisenberg had meticulously crafted before filming began disappeared once Culkin showed up on location. Eisenberg and cinematographer Michał Dymek realized that Culkin was having trouble hitting his target, something he was rarely asked to do while playing Roman Roy in “Succession.” Dymek, perhaps best known for creating a film around the perspective of a donkey in the Oscar-nominated international feature “EO,” knew how to go with the flow.

“I think for him, following a donkey for six months was like chasing Kieran around the set,” Eisenberg says. “He's such a lively artist.”

“What you're saying is I'm an idiot,” Culkin says.

“We had storyboarded the movie six months before Kieran got there, which is, of course, what you do,” Eisenberg says. “And Kieran came in and basically said, 'Wait. Why am I here? 'Oh. Because we need to see your face.'”

“But how know what am I here? Culkin says, laughing.

“I've been an actor and I've never said that, ever!” says Eisenberg.

“Actually?” Culkin responds. You wonder why have a blocking essay if everything is already set in stone.

“No,” Eisenberg says, “for me, blocking rehearsals tends to be the director saying, 'This is blowing up on that side.' Don't stay there. You will die.'”

“Well, that's something I'm looking forward to when I make explosive movies,” Culkin says.

Has the cinematographer ever turned to you, Jesse, and said, “At least the donkey hit the mark once in a while”?

“There were some side conversations that touched on that irony,” Eisenberg says.

“Yeah, the professionalism of a donkey versus a guy who's been doing this for 30 years, yeah,” Culkin says.

“I think there were two donkeys, but not another Kieran, so we were stuck,” Eisenberg continues.

What Eisenberg immediately noticed about Culkin was his complete lack of pretension. Many actors, Eisenberg thinks, have a theater student vibe eager to please. Culkin, on the other hand, has a clear view of the industry, considering it fickle and nobody's friend. He's seen it all and finds most of it stupid. But that modest attitude has consequences: Culkin can't remember what he's doing in a particular take. Eisenberg would love to read a line or react and tell Culkin, “Do that again.” Do that again?

“There's no part of your body that thinks, 'Oh, this will be good for the scene,'” Eisenberg says. “He just does what he does. Live in the moment, especially with a character like this who is simply driven by some kind of spontaneous identification. Here the actor simply does what the character does, which is simply reacting in the moment without ego.

“And that's how Kieran lives his life too,” Eisenberg continues. “He is simply not overwhelmed by competitiveness, professional ambition or jealousy. I've never met anyone who really feels all those things we all wish we felt.”

“Meryl Streep played my mother,” Culkin explains, referring to Wes Craven's 1999 drama “Music of the Heart.” He tells a long story about his professionalism and egalitarian spirit, which is not unusual, he says. “Most actors are not pretentious. But when I see it on set, when I smell it, it bothers me. I attack them, I make fun of them, you know, I confront them directly and say, 'You can't do that.'”

Eisenberg and Culkin didn't really know each other before making “A Real Pain.” But when Eisenberg was 7, “Home Alone” was released, starring Culkin's older brother, Macaulay. Culkin had a supporting role. Eisenberg saw the film 17 times.

“I was kind of aware of the phenomenon of Kieran actually being each other's brother,” Eisenberg says. “I guess I knew it in some indirect way. But I wasn’t reading, you know, the exchanges.”

“I had no idea what that movie was about when I saw it and I was in it,” Culkin says. “I was at the premiere and I was dying of laughter. It was the funniest thing I had ever seen. “I had no idea what the movie was about.”

“How could no one explain it to you? You're on set 15 hours a day,” Eisenberg asks.

“'Drink this Coke, wear glasses, say what you memorized, look pretty, and go home,'” Culkin responds. “Devin Ratray, the guy who plays Buzz, lied to me and told me the movie was about him. And I believed him. And then when I saw it, the movie made me laugh and I said, 'Mac was on set the whole time.' It makes sense that the movie would be about him.'”

I read a review of “A Real Pain” that called it a light film with a heavy heart. Eisenberg wanted to convey the irony of longing to connect with the pain of your ancestors and at the same time being unwilling to experience, or even face, any discomfort in doing so. The seed of the idea came from an advertisement he saw that said “Guided tours of Auschwitz (with lunch).” Shouldn't we feel more distressed about life? How can we find meaning without dealing with painful things?

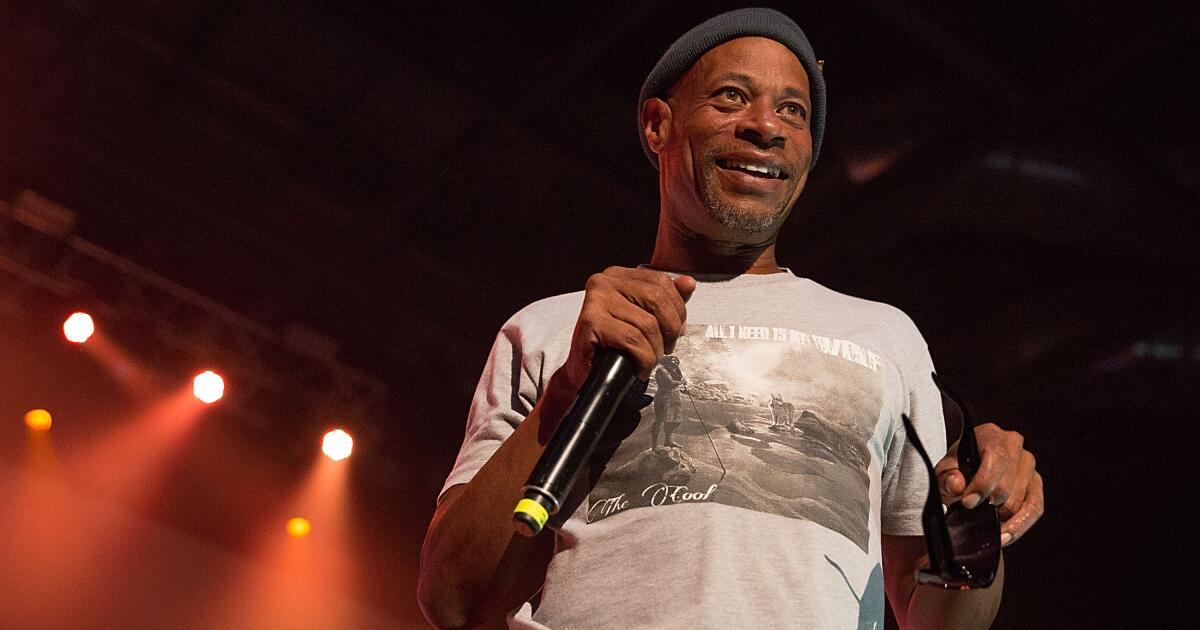

Kieran Culkin, left, and Jesse Eisenberg play cousins on a road trip in “A Real Pain.”

(Sundance Institute)

“That's my taste, but the problem with that taste is that it doesn't always translate to an audience,” Eisenberg says. “This is a movie where, through any set of miracles, the reaction is the same as my intention.

“Most of the time when you write something, the actor, at best, comes close to what you had in mind,” he continues, “and in this movie, especially that first day when I learned acting Kieran about the character, and his interpretation of it, I realized he was 100% there. I don't have to worry about that. And I've worked in films as an actor where the co-star is involved, and it's completely different from what was supposed to happen. what should be there. You meet with the director at the end of the first day and say, 'What the hell are we going to do?'”

“Those are difficult times,” Culkin says.

Eisenberg: “I've had those whole six times where you're like, 'The movie's not going to be what we've been thinking about for the last year.'”

“Good movies are a series of wonderful accidents that come together,” Culkin says.

“My dad always tells me, 'If you have four of those in your career, you must consider yourself a very happy person, a very lucky person,'” Eisenberg says.

Could you list four?

“No!” Eisenberg responds. “That's why I'm hungry.”

“I could name four that helped change my life,” Culkin says. “This would be one of them. The 'succession' was something very important to me, a series of miracles. And I did a play, 'This Is Our Youth,' where I felt like everything fell into place in the right way. And a movie, 'Igby Goes Down,' when I was 18, where it was the first time I felt, 'Oh, this is what it feels like to do something where everyone is on board and excited, and you don't know.' how it's going to turn out, and you see the result and you feel proud and happy.'”

He turns to Eisenberg. “Look, I actually named names.”

“That's good,” Eisenberg responds. “I eat…”

“Do you want to name names now?”

“Pretty much not.”

“'Scott Pilgrim vs. the World,'” Culkin blurts out. “I named another.”

Eisenberg shakes his head and smiles. They are miles apart, but he loves this boy.