Walking south on Vine Street past the Capitol Records building, musician Jessica Pratt recalled the first time she visited her current home in Los Angeles.

It was 2011 and I had recently seen “Mayor of the Sunset Strip,” a documentary about the infamous Rodney Bingenheimer, DJ and nightclub owner, which exposes the glitz and sleaze of the 1970s music scene. It also introduces outside figures, such as Ronald Vaughan, a friend of Bingenheimer's who has self-released music as “Isadore Ivy, astronaut at large.” Still picking up the strange frequencies of Los Angeles, Pratt saw Vaughan wandering outside the Capitol building; She probably wasn't there on business, was she? -and he couldn't help but be dazzled. “I thought, 'Wow,'” he recalled, “'I've really made it in Hollywood.'”

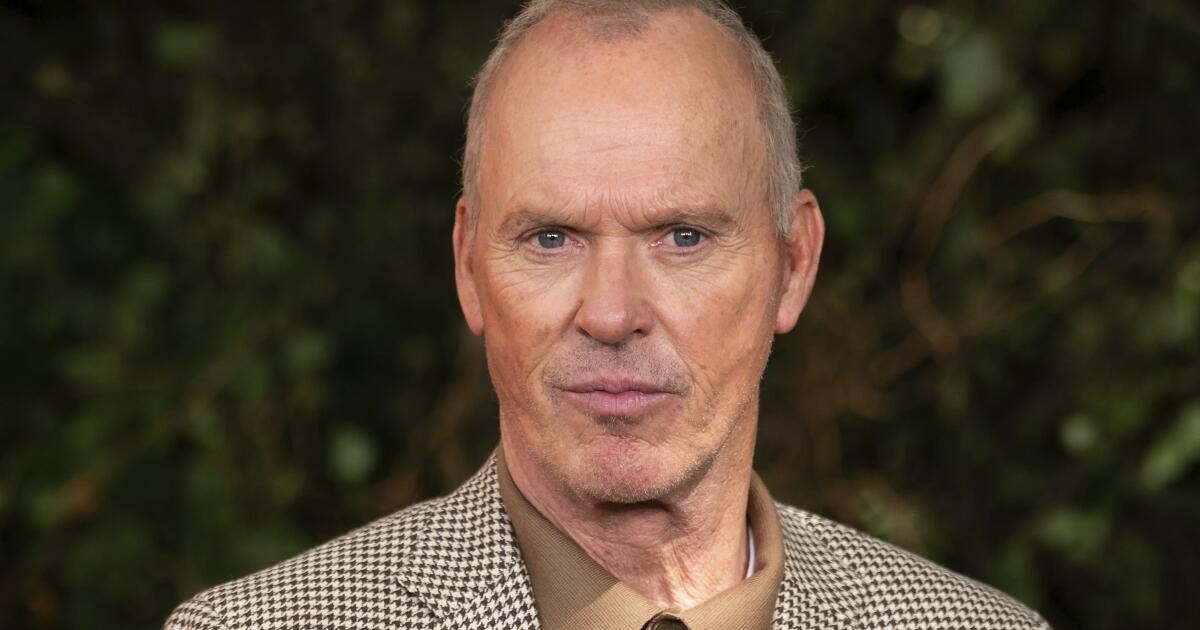

“I wear a lot of '90s youth clothes,” Pratt said, describing his signature black suit look.

(Linus Johnson / For The Times)

Pratt, whose new album, “Here in the Pitch,” is an anachronistic, dreamlike blend of folk music and chamber pop, is no longer a true outsider. But she clings to a love for the strange underworld of Los Angeles that often shines in broad daylight in places like Hollywood. Pratt still seems to belong to that group; As we headed toward Musso & Frank Grill, looking for a spot at the bar, her antique boots clicked on the pavement and her bleached blonde hair glistened in the spring sun.

“I wear a lot of '90s youthful mall clothes,” he said, describing his signature black suit look. Because of the changing times of thrift stores, he explained, it was increasingly difficult to find what he liked. “Which is sad,” she added, “because that's how I get a lot of my pants.”

Pratt, 37, grew up primarily in the Northern California town of Redding, but felt the pull of Hollywood before setting foot there. “Hollywood is collapsing,” he sang in the song. “Hollywood” from his self-titled debut LP, which was recorded in 2007, when Pratt was 19 years old.

A stroke of good luck led to the album's belated release in 2012: Tim Presley, the musician known as White Fence, heard the music via a remote connection and decided to release it himself. Pratt's early catalog, bolstered by 2015's more deliberate album, “On Your Own Love Again,” captivated a devoted fan base with a minimalist approach (mostly just nylon-string guitar and vocals) that hasn't been particularly viable since Leonard Cohen. It arrived in the late 1960s.

“It was definitely like stepping on a tapestry or a quilt or something,” said musician Angel Olsen, describing the feeling of discovering Pratt's records. “The way his voice and his harmonies continue in an endless stream, the way his melodic lines continue, like little separate rivers, it's really wild.”

Pratt's 2019 album, “Quiet Signs,” subtly expanded the palette, adding touches of instruments like piano and flute; From the outside, she felt like the most complete sonic realization of someone in control of a grand vision. But when Pratt listens to that record now, she returns to some of the most difficult years of her life.

In the time leading up to “Quiet Signs,” Pratt explained, she was dealing with the death of her mother and subsequently suffered a period of poor health. She was also going through the rekindling of a relationship with her father, who left the family when Pratt was 5 and separated completely when she was 14 (her father wore down his body with addiction issues and eventually died of COVID-19 in 2020 . ) Pratt was “exhausted,” she said, unable to write music. “I tried, but I didn't really have the juice.”

“Here in the Pitch” is just 27 minutes long, and Pratt spent three years making it, returning again and again to a studio in New York, tweaking each arrangement, waiting until everything seemed right.

(Linus Johnson / For The Times)

Matt McDermott, whom Pratt had met when they worked together at Amoeba Music in Hollywood in 2014, helped her with her convalescence. Pratt was at Amoeba only for a short time, and at one point helped with events (“I'd be getting 'Weird All the Water Bottles or Whatever”), but remained friends with McDermott. The two eventually became romantically involved and are now engaged.

Along with Pratt's co-producer Al Carlson, McDermott ended up collaborating musically in the studio on “Quiet Signs.” And for “Here in the Pitch,” the trio didn't mess with the formula, except this time, Pratt's music was coming together with a brilliance and vigor that hadn't been there before.

“I think he's gotten stronger over this whole period,” McDermott said by phone from the home he and Pratt share in Elysian Heights. “And now you can really hear it, where his songs have a swagger that didn't exist in the past.” He laughed as he remembered Pratt walking through the door one day and telling him, “I just walked around the block listening to [Frank Sinatra’s] 'My Way' five times in a row.”

The swagger is clear in the album's opening sounds: a drum intro in the song's “Be My Baby” style. “Life is,” which is particularly notable for being the first time Pratt included percussion in his music. But the drums recede quickly and the record is sparse and ominous in places. In other words, it's still clearly a Jessica Pratt production, one in which restraint is as important a factor as her ornate melodies and idiosyncratic voice.

“Here in the Pitch” is just 27 minutes long, and Pratt spent three years making it, returning again and again to a studio in New York, tweaking each arrangement, waiting until everything seemed right. In an era of frenetic streaming, when people barely blink when Taylor Swift releases a 31-track double album, it's particularly jarring to be given a slice of something that clearly doesn't care about maximizing every aspect of itself.

“Just because of the machine we're up against,” said Ryley Walker, a notable indie-rock figure who also plays guitar on “Life Is,” “my tolerance for long periods of time between music has completely evaporated.” . . “Jessica has God’s gift of patience.”

Pratt said he was “certainly happier and more present making this record,” but he still sees sadness lurking in the music as well. The title “Here in the Pitch” refers in part to total darkness, and Pratt said he imagines the phrase as “a threat or a welcome to a realm of shadows.” There's something conspiratorial about a song like “The world on a string” that advances with a slow threat, as attractive as it is disturbing. “I want to be the sunshine of the century,” Pratt sings in that song, and his claim is complicated in the song's video, which appears to be a confusing, colorful description of a cult gathering of some kind. It ends with Pratt, the cult's alleged leader, in a coffin.

“[This is] “It's the first time I've had the big push from the industry,” Pratt said. “It scares me a little bit, I won't lie.”

(Linus Johnson / For The Times)

When asked about the cult element, Pratt was unabashed about the way his fascination with Charles Manson wandered through his mind while making this record. There is the common element of human nature to be interested in “sordid and scary things,” of course. But Pratt's fascination is also guided by the way in which, from a certain perspective, you begin to feel sorry for the members of the Family, no matter how atrocious they were to innocent people. “I don't know, man,” he said, “I think a lot of people might fall for the same thing. “To me, it's no different than being in a gang or something, killing people and going to jail for it.”

Pratt also can't deny that the song with nylon strings and Manson's voice “Watch your game, girl” influenced his music, particularly his groundbreaking 2014 song, “Come back, baby” which was recently sampled by pop star Troye Sivan. “Believe [Manson] He really did it with that one,” he said, “and then he never did it again.”

Manson, who generated some genuine interest as a songwriter before turning against the world, is perhaps Los Angeles' ultimate musical outsider. His story is a grim reminder of how poisonous the business can be for those looking to make it big, but Pratt can't help but feel a little uncomfortable finding himself on the luckier side of things.

“[This is] “It’s the first time I’ve gotten the big push from the industry,” she said, sitting at the Musso & Frank bar, doodling little stars and hearts on a napkin. “It scares me a little bit, I won't lie.”

Pratt made a name for himself with simple recordings, but now he's found a broader focus on “Here in the Pitch.”

(Linus Johnson / For The Times)

Typically, when Pratt is asked what her songs are about, she responds that while they all have “meaning” to her, they aren't really about anything in particular. Not so with the album's finale, “The Last Year,” which she readily admits is about her and McDermott. “I think we're going to be okay,” she sings over a chord progression that feels almost elemental, like you can't believe someone else didn't think of it before her. “I think we'll be together.” It's an optimistic song but also a little hesitant. Pratt is better now, but she still sees striking images when she looks in the rearview mirror.

“Even if you recover from something like that,” he said, describing the trials at the heart of the song, “you have this kind of propensity to go a little crazy. I definitely don't think I have the strongest mental health of anyone on the planet. It's like, 'This is how it is and I'm trying to do the best I can.'”

As we walked the Hollywood Walk of Fame, Pratt mentioned a theory that there might be only male waiters at the 105-year-old Musso's. But after settling in at the bar and discussing what celebrities we'd seen there (Pratt's favorite sightings were comedian Fred Willard and writer and musician Pamela Des Barres), we noticed a waitress. Progress, I murmured.

“To be honest, I don't really care,” Pratt said. “If they want to live in the past, I don't care.”