While riding down Highway 101 in the backseat of his manager's pickup truck on a recent rainy afternoon, Sam Beam talks about his kids' lunches, specifically how annoying it is when they don't eat what he gets up early to make for them.

“Same goes for dinner,” he says in his soft Southern accent. Beam, who is 49 and makes spectral but meticulous folk music under the name Iron and Wine, lives in Durham, North Carolina, and has five daughters with his wife (though not all of them live at home anymore).

“You find something new that you are excited about doing and you put it on the table. Without any interest.“ He laughs. “I said, 'Okay, tomorrow you'll be alone.' Best of luck.'”

He jokes because he cares: Beam's latest album, “Light Verse,” is Iron and Wine's first studio LP since before the pandemic, a period of creative frustration for the songwriter who nonetheless believes it improved their relationship. with his kids.

“I travel a lot,” he says of his life as a musician, “and as they become teenagers, unless you put time into them, they don’t really give anything away… if you disappear. I mean, they’ll hold it against you. But they’re not going to say, ‘Maybe I could try to get closer to Dad.’” Because of COVID, though, “I was suddenly closer than ever,” he adds. “It was definitely a silver lining.”

The long stay at home might be why Beam sounds preoccupied on “Light Verse” by thoughts of time, memory, manhood and the pleasures and obligations of love. “What goes in is never what comes out / The hole in a garden ball, some pieces of shell,” he sings amid a tangle of acoustic instruments on “Tears That Don’t Matter.” “You’re just empty like a lost and found object / Sounds of a house, the tip of a candle.” On the tender “Taken by Surprise,” he muses on the impermanence of a goodbye; “Angels Go Home,” an austere ballad shadowed by strings, closes the album with a rhyme of “sons and daughters” and “stones in holy water.”

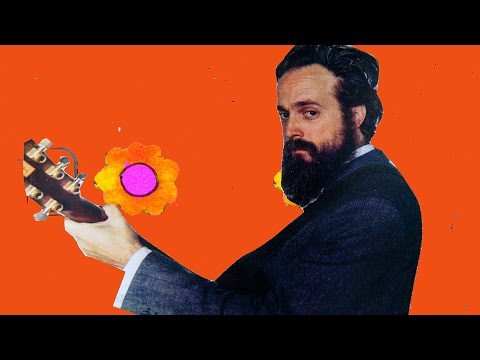

Beam recorded “Light Verse” in Los Angeles, a city he had visited frequently, if somewhat reluctantly, for various promotional assignments throughout his two decades with Iron and Wine. “Normally, the areas you work in are kind of crappy,” he says over dinner at a Hollywood restaurant. The singer, whose piercing eyes and scruffy beard give him a wizened philosopher look that belies his sly sense of humor, is in town rehearsing with his touring band in Burbank ahead of a tour that will bring him back here to play the Bellwether on Friday and Saturday nights. “It’s hectic and kind of rushed, and then you just go.”

However, this recording project was different: Sebastian Steinberg, who has played bass with Beam for about 10 years (and who also plays with Fiona Apple), recommended that he take up residence at producer Dave Way's studio in the relative wilderness. from Laurel Canyon. They assembled a band of crafty Angelenos, including guitarist David Garza, keyboardist Tyler Chester and Dawes drummer Griffin Goldsmith; Apple even contributed vocals to a waltz duet, “All in Good Time,” featuring Beam’s breathy croon against her earthy rasp. The pace was relaxed, the vibe exploratory. Beam says, “I've always loved the idea of people coming to California looking for some kind of freedom.”

For all its ties to Beam’s personal experiences, the songs on “Light Verse” aren’t strictly diaristic in the style of many 2020s compositions; he uses his imagination to take real-life characters in fictional directions and often revels in the pure sound of the words. “Pigeons are losing lucky feathers in the sky / Appaloosas in the moonlight are going blind,” he sings on “Yellow Jacket.”

“I use things from my life as a starting point,” says Beam, “but I don't want to have to be faithful to the story, like we're in a court of law. A song is not an essay about a certain point I want to make. “It’s about interacting with the language to see what happens.”

One of the album’s prettiest tracks, a delicately finger-picked tune called “Cutting It Close,” opens with an unexpected couplet made all the more jarring by the tenderness with which she sings it: “Long-lost friend of mine / I know we only fucked a couple times.” When asked where the line came from, she laughs. “My process is just strumming and humming syllables, and that phrase came up at some point. I was like, ‘Okay, that’s pretty rude. ’ But it sets you up for something complicated, which is a fun place to be as a writer. Where do you go from there?

Several songs, including “You Never Know” and “Taken by Surprise,” employ choruses that Beam repeats over and over until the words become mantras; In fact, the music's intricate rhythmic play (“Anyone's Game” is downright funky) seems as important to Beam as his soulful melodies, though he knows the latter are what his fans tend to prioritize. “Emotional porn” is what he calls what he believes makes people come to him.

“In another life I hope to be a drummer,” he says, smiling. “I like to be in the middle of the movement. For me, movement is where the voice always comes from.”

Beam, who is about to turn 50, has been doing some thinking about his place in a music industry that seems so far away when he's at home making uneaten lunches. It emerged in the early 2000s, “during the last vestige of monoculture, where everyone looks for what comes through certain channels.”

Venerable Seattle indie label Sub Pop signed him thanks to some lo-fi demos he'd made, and he quickly “fell into the laps of Sub Pop listeners, happy to give whatever they offered a chance.”

Today, she watches her daughters discover songs through TikTok’s mysterious algorithm and wonders how a new artist can reasonably predict anything about their career. Then again, Beam couldn’t have foreseen the success of her quiet acoustic cover of the Postal Service’s “Such Great Heights,” which achieved a prime version of virality when it was featured in the 2004 film “Garden State,” and now has more than 84 million streams on Spotify.

Would you say you ever feel like a famous person? You look around the crowded restaurant as if to say, Do you think anyone recognizes me here? (Even with the beard, that's a no.) What about in Durham? “I mean, it depends where you go,” you say. “If I go to the hippie store, they know who I am. If I go to Home Depot, they don't give a damn.”