When filmmaker Rich Peppiatt began working with the three members of Belfast hip-hop group Kneecap to create a film around their groundbreaking story as Irish-speaking rappers, he jokingly created a WhatsApp messaging group called “Kneecap Go to Hollywood.”

“These were things we were talking about in the pub in 2019 over pints,” says Peppiatt. “It all seemed like a pipe dream.”

And so it’s pretty remarkable that, just over four years later, Peppiatt finds himself in a hotel room just off the Sunset Strip with band members Móglaí Bap and DJ Próvaí to talk about their collaboration on the film “Kneecap.” (Member Mo Chara was unable to make the trip to Los Angeles.) A raucous tale that mythologizes the trio’s energy and sensibility in the tradition of “A Hard Day’s Night,” “Purple Rain,” “Spice World” and “8 Mile,” “Kneecap” won an audience award when it premiered earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival.

“Obviously it was the ambition,” says the director, “but we could never have dreamed that it would turn out so well.”

English remains the dominant language in Ireland, and the film shows the rappers running afoul of radio programmers, local political groups and authority figures of all kinds, in part over their use of Irish, as well as the content of their lyrics, which mix anti-colonial politics with hedonistic exhortations to drug use and partying.

“A lot of the big turning points in the film are based on truth,” says Móglaí Bap of the film’s evocation of his rise.

“Some of the most mundane things in the film are fake,” Peppiatt adds.

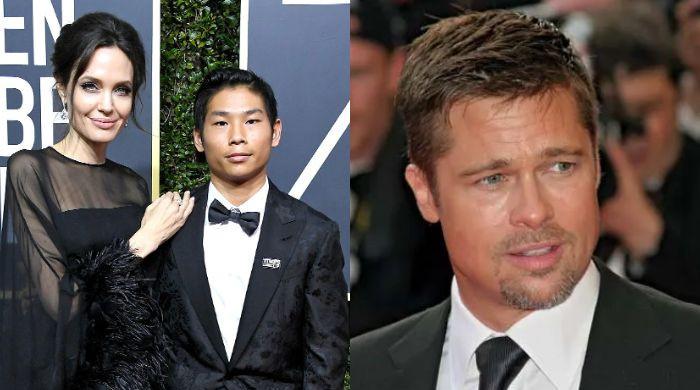

DJ Próvaí, left, Mo Chara and Móglaí Bap of Kneecap, photographed at the Sundance Film Festival in January.

(Mariah Tauger/Los Angeles Times)

DJ Próvaí was actually a schoolteacher when the group started in 2017, so he began wearing a balaclava covering his face on stage to conceal his identity. (And, according to the film, he once pulled down his pants to show “Brits Out” written on his bum.) However, Móglaí Bap’s father, played in the film by Michael Fassbender, was not a fugitive from the law.

“These characters represent where we come from and the people we grew up with,” Móglaí Bap explains. “So it’s not just our story, it’s everyone’s story. For example, half of my class had parents who had been members of the IRA. So it’s not always necessarily our personal story, but the collective story of Belfast.”

The group didn't set out to become the centre of attention in a movement to revive the use of the Irish language, which they have unwittingly become thanks to their headline-grabbing antics and instinctive style. At first, the band simply wanted to talk the way they talked to each other, among friends.

“Obviously when you speak a language that not many people speak, it’s a sense of pride and honour to speak that language and you want to represent it,” says Móglaí Bap. “But in the beginning, when we started, we just wanted to do it for fun. We had no intention of anyone outside of Belfast hearing our music. We didn’t even have any intention of starting a band, because obviously there had never been anything like that before.”

“Kneecap” specifically points out that language does make a difference. There is a stark distinction between saying “Northern Ireland,” the country’s official name as part of the United Kingdom, and “the north of Ireland,” for those who believe in a unified Ireland in opposition to colonial power.

“I found it very inspiring and very political, the idea of rejecting even the language of the country you lived in,” Peppiatt says of his initial interest in the band for his feature-length fiction debut. “To say, ‘You know what? Not only do I not recognize this country I live in, but I’m going to reject even the language. ’ It was a very powerful statement about what your beliefs are.”

Kneecap's political vision doesn't stop at Ireland's borders, however. The group has long been vocal in its support for Palestinians. Cast members of the film attended a pro-Palestine rally in Park City, Utah, during the film's Sundance premiere.

“We don’t see it as a massive political act to talk about what is happening in Palestine,” says Móglaí Bap. “It is simply seen as people defending human rights, who are being bombed from the sky. And that is what is happening in Palestine. War crimes are being committed. And I think that when war crimes are committed, they must be denounced.”

“What you also have to understand is that there has always been a connection between the people of Ireland and the people of Palestine,” Peppiatt adds. “That sense of being under the yoke of a colonial power is something that has haunted the Irish people for 800 years. I know it’s a very hot topic in the United States and it can seem controversial to show support, but in Ireland it’s the other way around. Being pro-Palestine in this situation is the default attitude.”

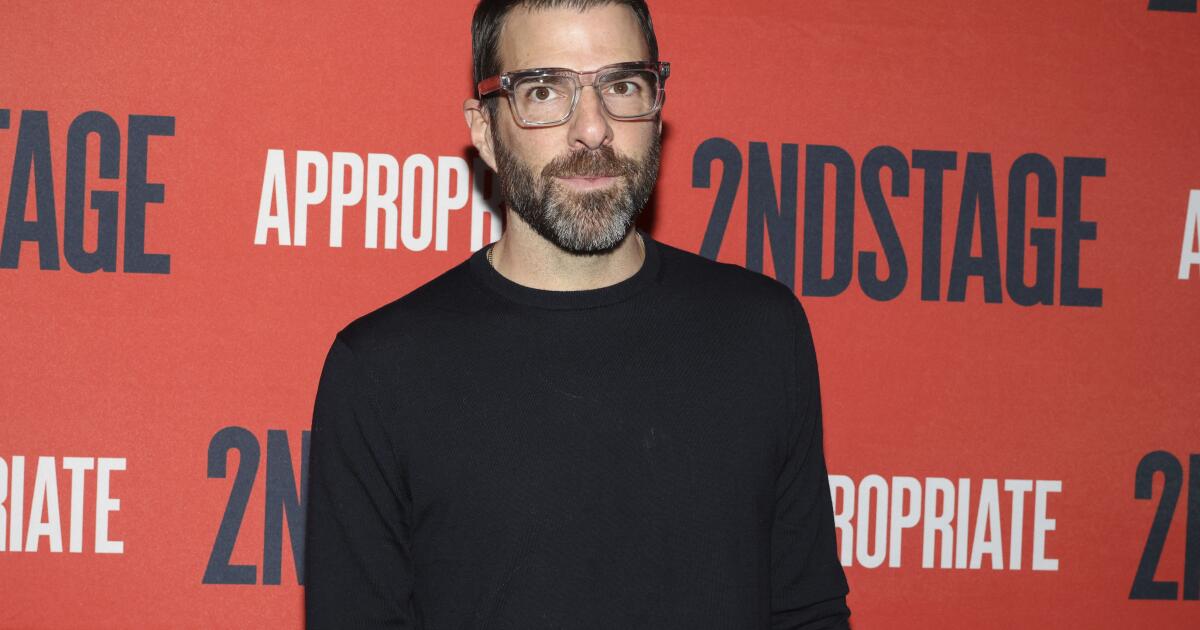

“Kneecap” director Rich Peppiatt photographed at the Sundance Film Festival in January.

(Mariah Tauger/Los Angeles Times)

Peppiatt is a former tabloid journalist (his 2011 resignation letter became a story in itself) who made a satirical documentary in 2014, “One Rogue Reporter,” specifically about his decision to leave the industry amid the phone-hacking and ethics scandals then rocking the British media.

Having moved into writing and directing for television, Peppiatt was immediately impressed by Kneecap’s energy when he first met them. However, he recalls how fantastic the idea of a film about them seemed when he first approached the band.

“The idea of making a film about a local Irish band that was unsigned, had never released an album and rapped in a language that not many people spoke doesn’t seem like a blockbuster movie,” says Peppiatt. “It seemed like a very specific and illogical thing to make a film about. But that’s the real reason for making this film.”

With “Kneecap,” he’s made a different kind of musical film, one that unfolds as it happens. “The idea of making a kind of real-time biopic, [about] “A band that practically follows what they do while doing it was in itself a genius concept,” he says.

At first, Kneecap members were understandably wary of the motives of this Englishman who approached them to tell his story.

“The English have a bad track record of trying to profit at the expense of the Irish people,” says DJ Próvaí.

After six months of Peppiatt hounding the band, they finally started talking to him and eventually agreed to the idea. (The film's script is credited to Peppiatt, with a nod to the band members in the story.) Eventually, Peppiatt even convinced them to take acting lessons before filming began.

“Once the film was finished, everyone who was working on it would move on to the next film and we would still be Kneecap,” says Móglaí Bap of their commitment to the project. “For us, as a band that is Kneecap, if the film is shit and we are shit and Rich is shit, then our musical careers, I imagine, would be over.”

“I mean the challenges that Rich had to deal with as well, trying to give us direction,” DJ Próvaí says. “We played ourselves, so we knew exactly what we were going to do. So that was what honed it to make sure it was real and genuine and authentic as well. But you have to give Rich credit for taking it all in.”

With their mix of irreverence and liberationist politics, Kneecap captures the attitude of people who want to be taken seriously without having to act totally serious all the time. Peppiatt notes that when he first went to an evening class to learn to speak Irish while embarking on the project, a handful of other people were there because they were Kneecap fans. As the band's profile has grown, those classes have only gotten more crowded.

Móglaí Bap sees it as a shared drive to escape the boundaries prescribed by native culture. “We’ve broken away from that,” he says. “And I think that’s what really bothers people, that we’re using language in a modern way. And I think it’s happening all over the world. With indigenous cultures, they say, ‘We’ll let you have your culture, but you have to express it in a certain way.’ We use language in a way that doesn’t fit their perception.”