You might notice something different about Wes Anderson’s “Asteroid City.” It looks a little austere, at least by the baroque design standards that distinguish the director’s “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” “The French Dispatch,” “Isle of Dogs” and “Moonrise Kingdom.”

All of those productions, as well as “Asteroid,” were designed by Adam Stockhausen, who began working with Anderson as art director on 2007’s “The Darjeeling Limited” and won an Oscar for “Budapest.” A Wisconsin resident and Brooklyn-based Stockhausen also frequently collaborates with Steven Spielberg (“Bridge of Spies,” “Ready Player One,” “West Side Story”) and Steve McQueen (“12 Years a Slave,” “Widows” , the next “Blitz”). ). In addition to “Asteroid,” Stockhausen’s work was also seen in a little thing called “Indiana Jones and the Doom Dial” this year, as well as Anderson’s short film adaptations of four Roald Dahl stories for Netflix.

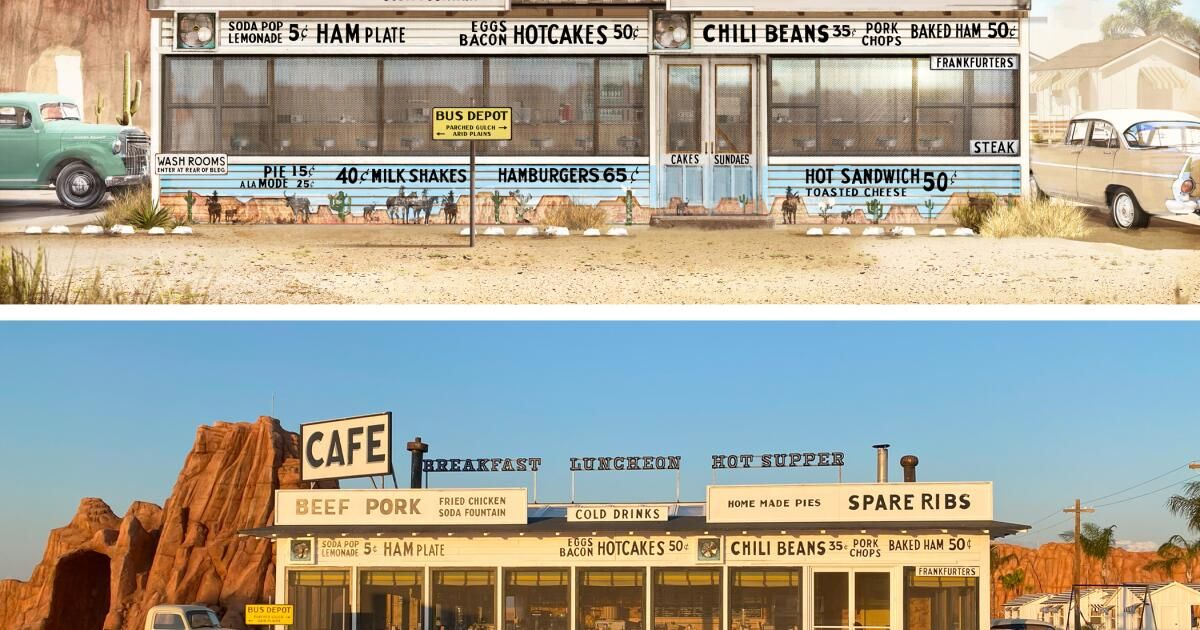

But don’t assume that distraction was a factor in the “Asteroid’s” deceptively simple visual impression. Stockhausen built an entire 1950s southwestern town for the show. It was fully functional, with electrical and plumbing infrastructure, plus clever, camera-compatible mechanics. Oh, he and made a whole desert to locate Asteroid City. Everything that looks simplified was a carefully planned trick of the eye.

“It’s very detailed, it was very studied, and we put a lot of thought into every element of it,” Stockhausen says via Zoom from New York. “However, it is not crowded; It is agile and simple. Whatever we did was going to be seen in that opening shot of the train going through Asteroid City, so we couldn’t go crazy and let any part get too big and out of control.”

Built on a horizontal expanse of more than 100 adjacent agricultural plots on the outskirts of the town of Chinchón, near Madrid, Spain, the Asteroid City set was covered with red dirt from a nearby quarry to approximate magic hour in Monument Valley.

“Asteroid City” production designer Adam Stockhausen created a desert for the film using tricks like forced perspective and imported red sand to hint at magic hour.

(Adam Stockhausen)

Carved foam mountains and tables, real and artificial cacti of various sizes, and forced perspectives were placed, sometimes 1,000 feet away, behind perfect small-town era recreations of a diner, gas station, and motel cabins. . A pile of dismantled cars, radio telescopes of different scales, and an unfinished highway ramp leading to nowhere are visible from the first shot of the train. The locomotive itself was a detailed miniature that a full-sized human could ride on. Perpendicular to the tracks is a kilometer-long road that accommodates recurring police chases that end in what looks like a matte painting but is actually a vanishing point where the manufactured desert meets the Spanish sky.

Another view of the Adam Stockhausen-designed “Asteroid City” highway reveals a distant vanishing point and a ramp leading to nowhere.

(Adam Stochausen)

“It’s all real,” Stockhausen confirms. “Our Asteroid City is manufactured there. When you look out the restaurant windows, you see the rest of our city. We worked hard to make that possible. Many of our early discussions were about lighting, how we could show exposure to the blazing sun considering how bright it would have to be inside that dining room.

We made the entire upper part of the dining room come out to create a giant skylight so we could do entire scenes without a single film light, have exposure inside and outside the building. That brings a level of reality; It’s there, right on camera; We’re not playing with that. In a weird way, you’re taking a location that’s completely a gimmick, but then you’re filming it without gimmicks in some sense. “It plays with reality in a very interesting way.”

Of building the entire set from scratch, Adam Stockhausen says: “We can design it exactly how we want. We can say, ‘Does that rock look better behind the gas station or the diner?’”

(Philip Vukelich / for The Times)

Paradoxically, the artificiality that is a hallmark of Anderson’s style is thematically doubled here. The sunlit, pastel-colored Mediterranean city is, in the film’s central conceit, the setting for a play being produced in New York City. The East Coast scenes are presented in black and white, the proscenium varied and backstage sets filmed in former 99-seat theaters in Chinchón and nearby towns.

In the Chinese box of storytelling that is “Asteroid City,” one layer of storytelling is represented by a show being filmed at a television station.

(Adam Stockhausen)

Parts of the crater of the ancient meteorite that gives its name to Asteroid City were also filmed in theaters. The stunning interior of a rustic beach house where Edward Norton’s playwright first meets the production’s star (Jason Schwartzman) was built into a fragrant but charming garlic drying warehouse.

In “Asteroid City,” playwright Edward Norton’s character types on a typewriter in a rustic, extremely detailed beach house, thanks to production designer Adam Stockhausen.

(Adam Stockhausen)

Why go to Spain and build this? Stockhausen and Anderson diligently studied American desert films both on location and on stages, such as “Ace in the Hole,” “Kiss Me, Stupid” and “Bad Day at Black Rock,” but they wanted the control and heightened appearance that it allowed. creating your own wasteland. .

“Asteroid City is a constructed space; It is a set designed for the work that is being developed,” says Stockhausen. “So it seemed completely natural to me that the place would be built, that it would have this kind of quality of being a stage. That was difficult to achieve in front of the real Death Valley. [near where ‘Black Rock’ was shot]. It has such a dominant look that anything you add to it is just a drop in the bucket, and we couldn’t get over it. Of course, there’s also the fun aspect of being able to design it exactly how we want, we can say, ‘Does that rock look better behind the gas station or the diner?’”

Every detail of “Asteroid City,” with its small town in the middle of a desert, was meticulously designed by Adam Stockhausen and his team. Here, a cowboy played by Rupert Friend considers the many and varied products offered by a row of vending machines.

(Adam Stockhausen)

It was the first time Stockhausen built his own fake but functional city. And it was mainly gas so that one could build, for example, vehicle cabins in which one could comfortably flirt or spend the night. But running a municipality is not all fun and games.

“If I had to do it all over again, I would definitely focus more on drainage,” says Stockhausen, amused and not joking. “We flattened the entire place for our 360-degree desert and put in what we thought was a substantial amount of drains to handle the water if it came. But it was no match when the real rains came towards the end of our shoot.”

Veteran production designer Adam Stockhausen, frequent collaborator of Wes Anderson, Steven Spielberg and Steve McQueen, photographed in New York on November 21, 2023.

(Philip Vukelich / for The Times)

Reality can certainly suck, which is probably a good tagline for any Wes Anderson production. But whatever it takes to create alternative settings for his films, the rewards are worth it.

“I love the motel and the way it is suddenly rearranged scene by scene,” says Stockhausen, a former opera set designer. “I love the chili diner, where the latticework that covers the entire space is really beautiful. And I love the image of that highway ramp that goes nowhere, that just sits in space. It is a sculptural object that is the largest thing in the city and yet it is useless. It is very beautiful.”

It sounds like another apt description of Anderson’s cinema.