Isabel Wilkerson’s 2020 nonfiction book “Caste” It is a kind of biography of an idea, and an elusive idea at that. Americans tend to be quite knowledgeable about race and class. Breed? Not as much, at least not as much as, say, in India, where artificial hierarchies are rigidly defined.

So when Ava DuVernay fell in love with the book and became interested in adapting it to the screen, she faced a challenge: How to turn Wilkerson’s central concept into a story? “She was trying to figure out how to get the information into the film that he wanted to convey emotionally,” the writer-director said in a video interview from New York. “There were characters in the book, but there weren’t enough in them to sustain an entire movie.”

As it turned out, he found the answer in the author herself. DuVernay’s new film, “Origin,” blends elements of “Caste” into the story of how Wilkerson, played by Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor, came to write the book during a particularly difficult time in her life, marked by the deaths of several beloved. , including her husband (played by Jon Bernthal). It is the story not only of an idea, but also of the woman who brought that idea to life through her research, her reporting, and her life experiences. In the hands of Duvernay and Ellis-Taylor, “Caste” and Wilkerson come to life.

It’s a bold tactic that pays big dividends. It also arises naturally from the work of Wilkerson, the Pulitzer-winning journalist and author of the Great Migration epic “The Warmth of Other Suns,” who has a gift for infusing history with the power of personal narratives. “That’s the brilliance of his writing,” Ellis-Taylor said from Los Angeles. “She takes these ideas that have made us lazy, that have essentially become abstractions, and she makes them very, very personal. The beautiful thing about the book, for me, is that it is as much a memoir as it is a historical or journalistic work.”

A brief introduction: Caste can be seen as an artificial hierarchy that helps determine status or respect. “That “Social hierarchy can apply to gender, sexual preference, nationality, ethnicity, religion, class, or race,” DuVernay says. “It is the basis of all our ‘isms’: racism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, homophobia, sexism.” In “Caste” and “Origin,” it can be applied to a German (Finn Wittrock) who falls in love with a Jewish woman (Irma Eckler) during the Third Reich, or to the Dalit people of India, who reside on the base. of the caste system of that country. Or Trayvon Martin, the Florida teenager who was shot and killed by George Zimmerman, essentially for walking in the wrong neighborhood, in 2012.

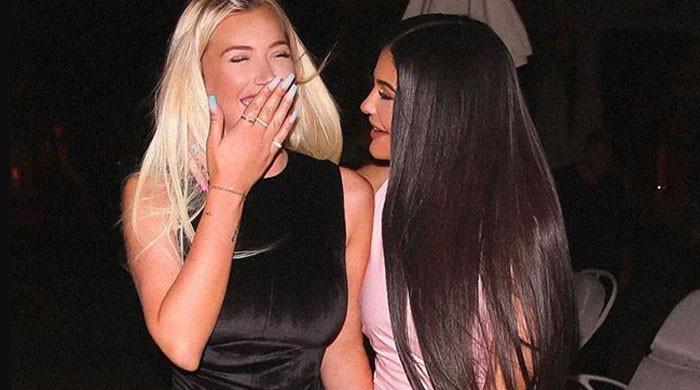

Jon Bernthal and Aunjanue Ellis star in “Origin.”

(NEON)

Martin’s murder was the impetus for Wilkerson’s book; As we see in the film, an editor approached her about writing an article about it, and the deeper she dug into it and the more connections she made to it, she came to believe that race was only part of the story. “Origin” begins with the death of Martin (played by Myles Frost); Your heart sinks as soon as you see him put his Skittles on the store counter.

Raised in rural Mississippi, Ellis-Taylor is no stranger to racial discrimination. But she appreciates how “Origin” and “Casta” go beyond those parameters and into something more complex.

“We use racism as a way to describe our social ills and the hierarchies in this country,” the actor says. “But you can be a black police officer who hits a black child, and you do it because you are operating as a tool in the hierarchy.”

“Race and class are important elements,” DuVernay adds. “But it is complicated”.

DuVernay has never shied away from that kind of material. In “Selma,” he dramatized the challenges facing civil rights activists, led by Martin Luther King Jr. (David Oyelowo), in the Deep South. In the miniseries “When They See Us,” she told the story of five black teenagers imprisoned for assaulting a jogger in Central Park in 1989; Their convictions were later overturned. In the documentary “13th,” he analyzed racial inequalities in the American prison system. “I’m interested in being a citizen of the world and trying to challenge the way we treat each other,” she says. “That’s what guides me when choosing projects.”

But with “Origin” she also saw the opportunity to tell a different kind of story, about the intellectual journey of a black woman. When we spoke, DuVernay had recently rewatched “Losing Ground,” a 1982 drama written and directed by Kathleen Collins, about an eventful summer in the life of a philosophy professor (Seret Scott). She was surprised and saddened by the uniqueness of it.

“She’s not doing intense academic research, and she’s not pursuing an intellectual goal, but she’s in a mental life,” DuVernay says of Collins’ heroine. “That’s a very rare thing for women on screen, and certainly for black women on screen. Seeing that work in the context of ‘Origin,’ I felt a real kinship with Kathleen Collins, as a descendant of her as a black filmmaker. The inner lives of so many people are traditionally left off the screen.”

Hollywood, after all, has its own hierarchies: its own caste system, if you will. By presenting the story Wilkerson told, as well as Wilkerson’s own story, DuVernay hopes to remove some barriers and show that even the most rigid systems can be shaken.

“Caste animates every aspect of our lives,” Duvernay said. “It’s something we don’t talk about, even though it’s central to much of what we experience.”