The new film “Sing Sing” is set in the eponymous maximum-security penitentiary, a gray, gothic structure in upstate New York that’s designed to punish its condemned inhabitants. But most of the film takes place in a sprawling auditorium, with vaulted ceilings and large windows that bathe the space in natural light.

Here a prison theater group meets several times a week, sometimes for a few hours, sometimes all day. When they work, they are not incarcerated men, but reckless pirates, Old West cowboys and Shakespearean antiheroes. They play improvisational games, try on costumes, recite lines and rehearse props; they laugh, cry and embrace their many emotions, as the best storytellers do.

As one imprisoned actor says in the film: “Brother, we are here to become human again.”

The phrase also serves as the thesis statement for “Sing Sing.” Inspired by the true stories of those who participated in a unique, real-world theater program, this intimate and captivating drama is arguably one of the most accurate depictions of acting in Hollywood — not just as a vehicle of expression or the foundation of a global industry, but simply as an exercise in imagining oneself as someone else for a moment. When practiced in community, the pastime of playing pretend can produce powerful and lasting change.

“Sing Sing” hits theaters today after receiving an audience award at South by Southwest, numerous rave reviews and plenty of Oscar buzz. Director Greg Kwedar attributes the film’s reception to the foundation laid by Rehabilitation through the artsthe volunteer-run theatre program founded at Sing Sing in 1996 and which has since expanded to include dance, music, visual arts and creative writing at eight New York State correctional facilities.

“Because of the way the show approaches acting as a tool for personal development, there’s an intense openness that happens in front of the camera,” the filmmaker says in a Zoom interview from San Francisco earlier this week, “a vulnerability to being uncomfortable and going for it that’s built among men through years of trust.” Kwedar, 39, and his co-writer, Clint Bentley, 38, developed their script while observing rehearsals, participating in workshops, attending screenings and meeting with RTA alumni, who make up 85 percent of the film’s cast and play versions of themselves.

Colman Domingo, center, and the cast of “Sing Sing.”

(A24)

While professional acting companies typically present classic texts with an emphasis on factual accuracy and dramaturgical logic, the RTA instead prioritizes the emotional authenticity of each actor. Theatergoers will notice this freedom from the start, when “Sing Sing” opens with “Rustin” star Colman Domingo, 54, playing the show’s founding member, John “Divine G” Whitfield. He’s acting onstage in the prison production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” reciting Lysander’s lines (“The course of true love never ran smooth”) with total commitment — and while sporting a gold crown.

“Why is he wearing that?” Domingo asks on a video call, laughing. “He’s not a king, he’s one of the lovers. Maybe it’s because that’s the costume they had. But regardless of why, that’s a choice that makes sense for these actors: our Lysander is wearing a crown, where’s the problem?”

RTA’s unwavering dedication to freedom is something rare in the world of theatre, and even more so in the world of prisons. “We all tell ourselves that there are set rules about who we are and how we have to be,” Domingo adds, “but what RTA says instead is that you don’t have to be anything that’s been instilled in you, the history that you came here with, or the trauma that you’ve suffered. You can actually break free and become something new. I think we as viewers crave that, to be given that permission so freely.”

“Sing Sing” follows a group of incarcerated actors through their new production: an original time-travel comedy that includes (but is not limited to) Egyptian mummies, gladiator battles, dance numbers, a monologue from “Hamlet” and a cameo from Freddy Krueger. The premise of the play is lifted directly from a Esquire article from 2005 about the prison program that initially caught Kwedar's attention, but the film focuses less on “breaking the mummy code” than on the incremental progress of learning to see oneself as a person capable of creativity and rebirth.

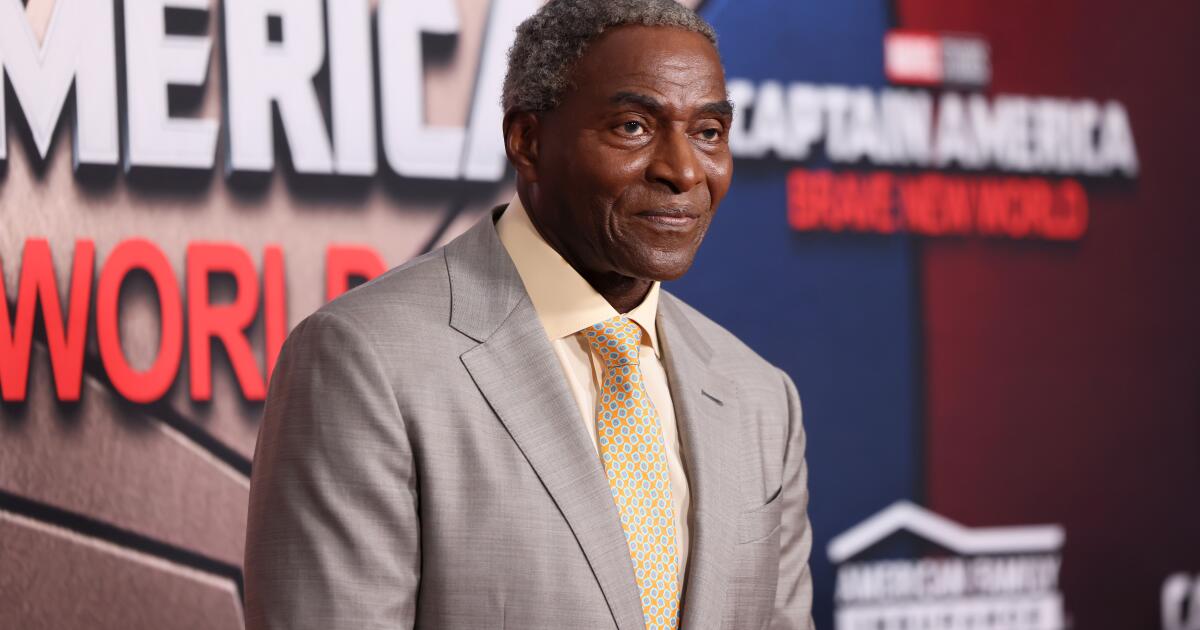

Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin plays a version of himself on “Sing Sing.”

(A24)

“It was cathartic, because I was able to work out a lot of frustrations and tensions, analyze them by playing other characters and see life through other eyes,” recalls Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin, 58, who, while incarcerated, initially wanted to join RTA to flirt with female volunteers. He went on to direct Sing Sing productions of “West Side Story,” “Jitney” and “Oedipus Rex.”

“I was always excited to go to rehearsals because I was entering a space of freedom, a space where I know I’m going to heal and have a good time,” she adds. “I know people would probably never think that, because it’s a prison. But that space wasn’t a prison, it was a prison.” our “The space. And doing plays and creating and having volunteers who come from outside and who really see me as a human being, for whom my opinion counts; that was a beautiful way to exist in a place that wanted to try to deny my existence.”

Throughout “Sing Sing,” between auditions for the play and opening night, actors rigorously prepare for their roles with dance battles, sword fights and improv games — the latter of which were not fully scripted but attempted on set — directed by “Sound of Metal” Oscar nominee Paul Raci, who plays veteran RTA volunteer playwright Brent Buell.

“These sequences of autonomous, light-hearted play were difficult to calibrate,” says Kwedar, “because we don’t want to trivialize what’s happening, which is actually quite significant. These were moments of childlike joy in the process of acting that were like full-throated shouts of joy. We made sure that the camera rarely looked away and always came in close, and danced with the same freedom that the men felt in that space.”

Domingo sees the inclusion of such images of vulnerability among men, especially men of color, as a radical act. “The world doesn’t see us like that,” he says. “We’re typically portrayed in hyper-masculine, hardened, deteriorating analyses of who we are, which then makes people think of us in a certain way in the world. But what I and my co-stars know to be true is that love, sweetness, joy and brotherhood are always available.”

James Williams, left, and Sean San Jose in the film “Sing Sing.”

(A24)

Kwedar says he and Domingo agreed that “Sing Sing” needed to be, “above all, honest, elegant and tender” — words one wouldn’t normally use to describe a film set in a prison. Rather than replicate the genre’s violent and dehumanizing clichés, the director renders the courtyard scenes, away from the work of the theater group, with a stillness, “like a Greek chorus that doesn’t have the freedom to move, the permission to speak or the ability to convey any kind of love or emotion. To me, that kind of numbness felt more horrifying than any bloodshed.”

“Sing Sing” was filmed over 19 days in July 2022, across several locked-down correctional facilities — a difficult environment, both logistically and for the formerly incarcerated actors to return to, even with a counselor in tow. “It’s all concrete and there’s no air circulation,” says co-writer and producer Bentley. “But every time the alumni filmed together, they brought so much joy that it far outweighed the misery of filming in that place. Walking into the space they’d created was like walking into the color of ‘The Wizard of Oz.’”

The film ends with footage of jubilant finalists from actual Sing Sing productions, footage captured by the RTA over the years not just for posterity, but to send home to the relatives of incarcerated cast members. The film doesn't concern itself with who gave the best performance on the show, nor does it say who becomes a professional actor upon release. It's not interested in such things.

“The performance we’re trying to challenge in this film is not about performing in front of an audience on opening night,” Kwedar says. “There’s a kind of falseness that can happen when you’re just memorizing lines and being technically excellent. It’s when you can step outside yourself and look through someone else’s eyes that the capacity for empathy is unleashed and a deeper truth emerges. And what that starts to build in you is something unparalleled.”

Director Greg Kwedar, left, and Colman Domingo on the set of “Sing Sing.”

(Phyllis Kwedar / A24)

“Sing Sing” makes it clear that acting is hard work, that creativity is a muscle worth exercising, and that dreaming is a discipline best taken seriously. Domingo and Maclin’s initially discordant characters discover a healthier perspective on themselves and each other; all those silly improv games and blocking rehearsals create an empathy and openness that allows them to forge a friendship. A real rehabilitation of sorts has occurred.

This resolution reflects the facts: A 2011 study by John Jay College for Criminal Justice found that those who participate in RTA programs have better social skills and fewer conflicts while in prison. And according to RTA, less than 3 percent of RTA members return to prison as repeat offenders, compared with 60 percent of incarcerated people nationwide.

These results make a strong case for anyone, whether incarcerated or not, to try the transformative power of acting.

“I hope we are aware of our power, of what we have to offer,” says Kwedar. “If this can happen within Sing Sing, it can happen anywhere. We don’t have to settle for misery. Art is as vital as the air we breathe, and wherever people have access to it, it can thrive.”