In the beginning was the Word, or as they call it in Hollywood, word of mouth.

For as long as there have been movies, studio marketers have been tirelessly searching for ways to get people talking about them. Whether it was through eye-catching trailers, glowing reviews, or recommendations from satisfied audiences, word of mouth was the engine that could organically turn a little-known film into an unexpected hit through the power of collective word of mouth.

In the 1990s, the explosive growth of the Internet promised to turn this engine into a high-speed global force, extending the reach of movie marketing campaigns into unexplored corners of what was still quaintly called “cyberspace.” But in an era when the concept of virality was still limited to infectious diseases, it took a low-budget, little-known horror film called “The Blair Witch Project” for the industry to realize the revolutionary potential of this new tool.

The 1999 project

All year long, we'll be celebrating the 25th anniversary of pop culture milestones that transformed the world as we knew it and created the world we live in today. Welcome to The 1999 Project from the Los Angeles Times.

Directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez on a shoestring budget of $60,000, “Blair Witch” was intended not to be a fictional story but rather the actual footage found on video cameras left behind by three young filmmakers who disappeared in the Maryland woods in 1994 while making a documentary about a mythical local hermit who kidnapped and killed children. When “Blair Witch” premiered at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival, the film’s cast, made up of unknown people (who had used their real names in the film), were listed as “missing” or “deceased.”

Artisan Entertainment acquired the distribution rights to the film for $1.1 million and set about creating a guerrilla-style marketing campaign that would further blur the line between what was real and what wasn’t. Lacking the deep pockets of a major studio to run expensive television ads, Artisan’s marketing team launched a website two months before the film’s release that expanded on the “Blair Witch” mythology with fictional police reports, newspaper articles and interviews.

John Hegeman, Artisan’s marketing director, believed strongly in the potential of the Internet and had created the first promotional website for the 1994 science fiction film “Stargate.” While a traditional studio film marketing campaign could easily run $25 million or more, Hegeman realized that the Internet could get the news to an even wider audience, at a fraction of the cost of print and television ads.

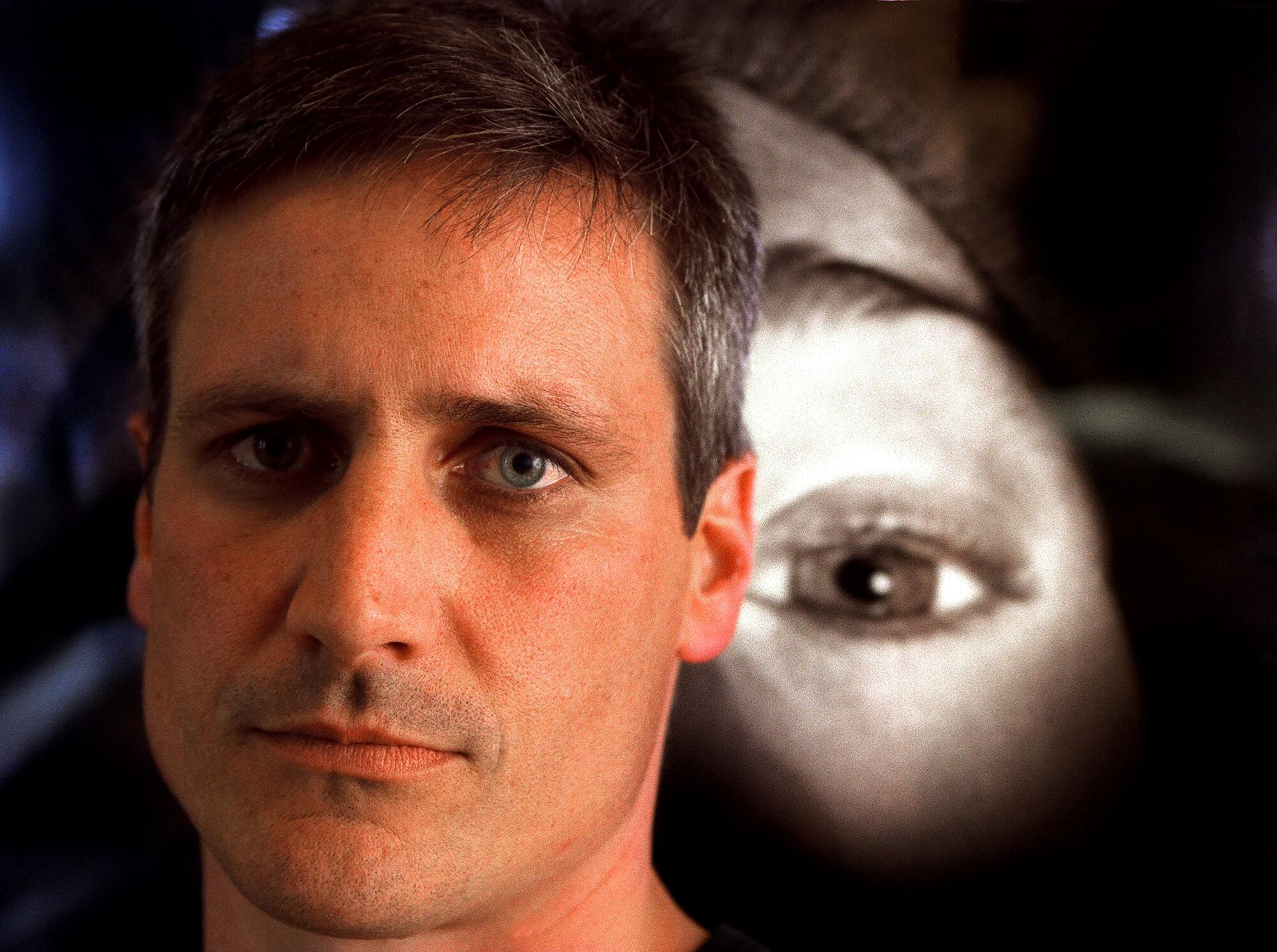

John Hegeman, who created the viral buzz around “The Blair Witch Project” for Artisan Entertainment, photographed in 1999.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

“There are a lot of other ways to reach people than throwing money at them,” Hegeman told The Times in a 1999 interview, noting that the film’s total pre-release marketing expenditure amounted to just $1.5 million. “When people say something can’t be done, that in itself is motivation enough to say, ‘Yes, it can. ’”

Within weeks of its launch, the “Blair Witch” site, which was regularly updated to fuel the mystery, was racking up 3 million hits a day. Artisan expanded the eerie marketing campaign with documentary-style trailers featuring raw, hand-held footage accompanied by frightened voices and screams. The company’s young interns were sent to cafes and dance clubs across the country to ask people what they knew about the supposed Blair Witch legend, armed with realistic-looking signs that read “missing” for the film’s three stars.

By the time “Blair Witch” was released in July 1999, anticipation had reached fever pitch and the rest of Hollywood had already taken notice. Jim Fredrick, a professor of entertainment marketing at Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts, was senior vice president of creative publicity at Warner Bros. at the time and recalls being surprised by how much buzz the independent distributor was able to generate through its grassroots campaign.

“The whole concept of found footage and asking the question, ‘Is this real or not?’ was just ingenious,” Fredrick says. “At any major studio, you have huge marketing budgets and you’re researching and trying things out. Artisan didn’t have those tools or the money, so they had to find other ways, and lo and behold, this thing called the Internet came along and it’s incredibly cheap, if not free. These guys fooled the world, like Orson Welles with his movies.” [the 1938 radio drama] “The War of the Worlds” and became a phenomenon.”

Respected documentary filmmaker Joe Berlinger has been hired to direct the sequel to The Blair Witch Project. Behind him is an image of the forest from the film.

(Bruce Gilbert / For The Times)

Opening in just 27 theaters, “Blair Witch” was an instant sensation with audiences, grossing a staggering $56,000 per screen, despite reports that some moviegoers vomited from the mix of fear and motion sickness induced by the film’s shaky footage. By the end of its theatrical run, the film had expanded to more than 2,000 theaters and grossed nearly $250 million worldwide — more than 4,000 times its original budget — making it one of the most profitable independent films of all time.

As the makers of “Blair Witch” worked to expand the film into a multimedia franchise that included books, comics, video games and a sequel, others in Hollywood attempted to emulate their formula. In the years that followed, films like “Cloverfield,” “Paranormal Activity” and “The Last Exorcism” embraced the found-footage concept with varying degrees of success. But recapturing the lightning-in-a-bottle cultural phenomenon of “Blair Witch” proved difficult as audiences became more adept at such marketing tricks.

“I can’t remember a horror movie I’ve worked on after 1999 where the producer hasn’t said to me, ‘Can’t you do for me what they did for ‘Blair Witch’?’” Fredrick says. “It’s very frustrating to have to say to the producer, ‘No, you don’t understand, we can’t repeat history here. ’ Audiences have become very smart and it’s very hard to fool them. We’re talking about the stars aligning in a way that may never be repeated again.”

Still, though it may have proven difficult to replicate, “Blair Witch” offered proof of concept for the power of internet-based marketing, prompting studios to look for innovative ways to reach audiences through interactive digital campaigns and shared experiences rather than traditional media. More broadly, it helped usher in a new era of pop culture in which the lines between fact and fiction would become increasingly blurred.

A quarter-century later, Fredrick says even young students in his film marketing course, who were born in the smartphone era, recognize the pivotal moment that “Blair Witch” represented.

“Every semester, I have an assignment for students to present a case study of their favorite marketing campaign, and every semester someone brings up ‘Blair Witch,’” she says. “Even though they weren’t alive when the movie came out, they’re impressed — and a little bit amazed — by the gullibility of people who believe this is real. That’s a real nod to how effective ‘Blair Witch’ was. People love unraveling a mystery.”