Pillows are fluffed, cocktails are mixed, enchiladas are heated in the oven. Ilana and Enrique Gómez have done everything they can to prepare their Pasadena mansion for the arrival of their daughter's boyfriend. But nothing could prepare them for who turns out to be the person standing at their front door.

In Gloria Calderón Kellett's new play, “One of the Good Ones,” this scenario leads to a frank conversation, unfolding in real time, about unconscious bias, intergenerational expectations, and who can claim Latino and American identity. (Between spitting, suffocating and hitting a very full piñata, of course).

“'Guess Who's Coming to Dinner' meets. 'Dishonor'” principal Kimberly Senior joked. “And even though it's a one-act play, the second act is the conversation you're likely to have afterwards.”

While the play's title reflects how the parents on stage (Lana Parrilla and Carlos Gómez) view their only daughter (Isabella Gómez), it also reflects how Calderón Kellett, one of the few Latina showrunners in the industry (“One day at a time,” “With love”), says she has been greeted during her career in Hollywood: with “zoo animals' fascination with what it's like to be a non-white man telling stories.” And the world premiere comedy, which runs through April 7, is the first Latin commission in the film's 100-year history. Tony-winning Pasadena Playhouse – a milestone worth celebrating, albeit long overdue for a Los Angeles theater company.

Ahead of the play's opening night on Sunday, Calderón Kellett had a candid conversation with The Times about writing Latino characters who are thriving, learning about theater from Norman Lear and making even the most difficult conversations fun.

How did “One of the Good” come about?

I wanted to write something about the complexities of identity. Before the strike, I talked to Danny [Feldman, artistic director of the Pasadena Playhouse] about the fact that, although I have been a [television] writer for 15 years on many shows, When I did “One Day at a Time”, The only thing people were interested in talking about was my Latinidad. I'm happy to talk about it, because I love who I am and I'm proud of my parents and where they come from, but it's all people wanted to talk. And he would understand it from both sides, from the white perspective and from the Latino perspective: this kind of fascination with zoo animals for what it's like to be a non-white man telling stories.

So I had to navigate being a storyteller and constantly defending your point of view in the world, which I found strange because it's not something my white counterparts ever have to do. [“One Day at a Time” co-showrunner] Mike Royce said: “Man, I can only show up and tell stories and jokes, you have to come with the weight of the world on your shoulders to represent your community. What you have to do is much more difficult and I see you.” I burst into tears and he hugged me.

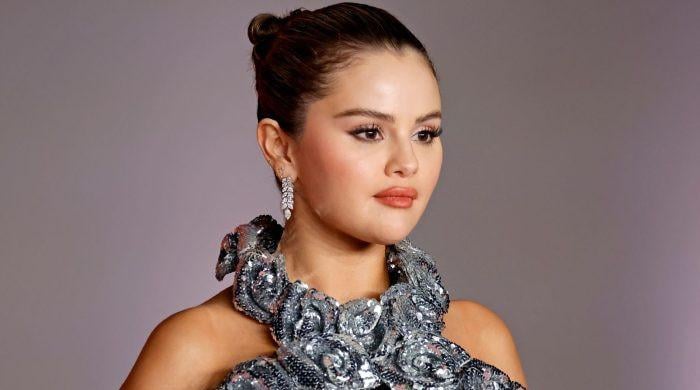

Isabella Gomez, Carlos Gómez and Lana Parrilla in “One of the Good Ones” at the Pasadena Playhouse.

(Jeff Lorch)

The work analyzes identity (Latin and American) from multiple perspectives within a family: one of the parents is of Puerto Rican and Mexican descent, the other is Cuban with grandparents from Spain. What inspired these characters and their conversation?

Having to navigate those spaces myself. I'm a West Coast Cuban who grew up in Portland, Oregon, and then San Diego. And then in Los Angeles, I was constantly told, as an auditioning actress, that I wasn't Latina enough, that I wasn't dark enough, that I needed more of an accent to play this Latina character. I am literally 100% Latina! So is identity based on where you live, where your parents lived, What language do you speakWhat do you think it should look like?

I also wanted it to be an intergenerational conversation. When writing “One Day at a Time,” I had many conversations with my old people about LGBTQIA issues and using latino/latina/latinx — all those things, they don't know anything about it, they think it's crazy. But I loved talking to them about these things, all asking questions and trying to understand each other. So although everyone [onstage] It's right and it's wrong, and although they may not get any definitive answers at the end of the conversation, they are able to talk about it, break it down, and maybe, in time, understand it; answer.

This discussion takes place in real time, and while it gets tiresome at times, it's also hilarious. How did you find the fun in such complex topics?

The idea of who gets to claim an identity, that fine line between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation, is very interesting! And one thing I wanted to do: There are lines in here that white people constantly say to Latinos in real life. Like, “Where are you really from?” “Some of our best friends are Latino!” We get those things all time. So I deliberately wanted to see that in the mouths of the Latino characters, let this conversation unfold and let the audience be a fly on the wall in this house.

And in all storytelling, specificity is universal. I mean, there wouldn't be anyone who walked through that front door who would have been good enough for his daughter, and that's something every parent can relate to. So if you're not Latino, there will still be things here that resonate with you. I hope the audience laughs a lot and then talks for hours. For me, that would be the biggest victory.

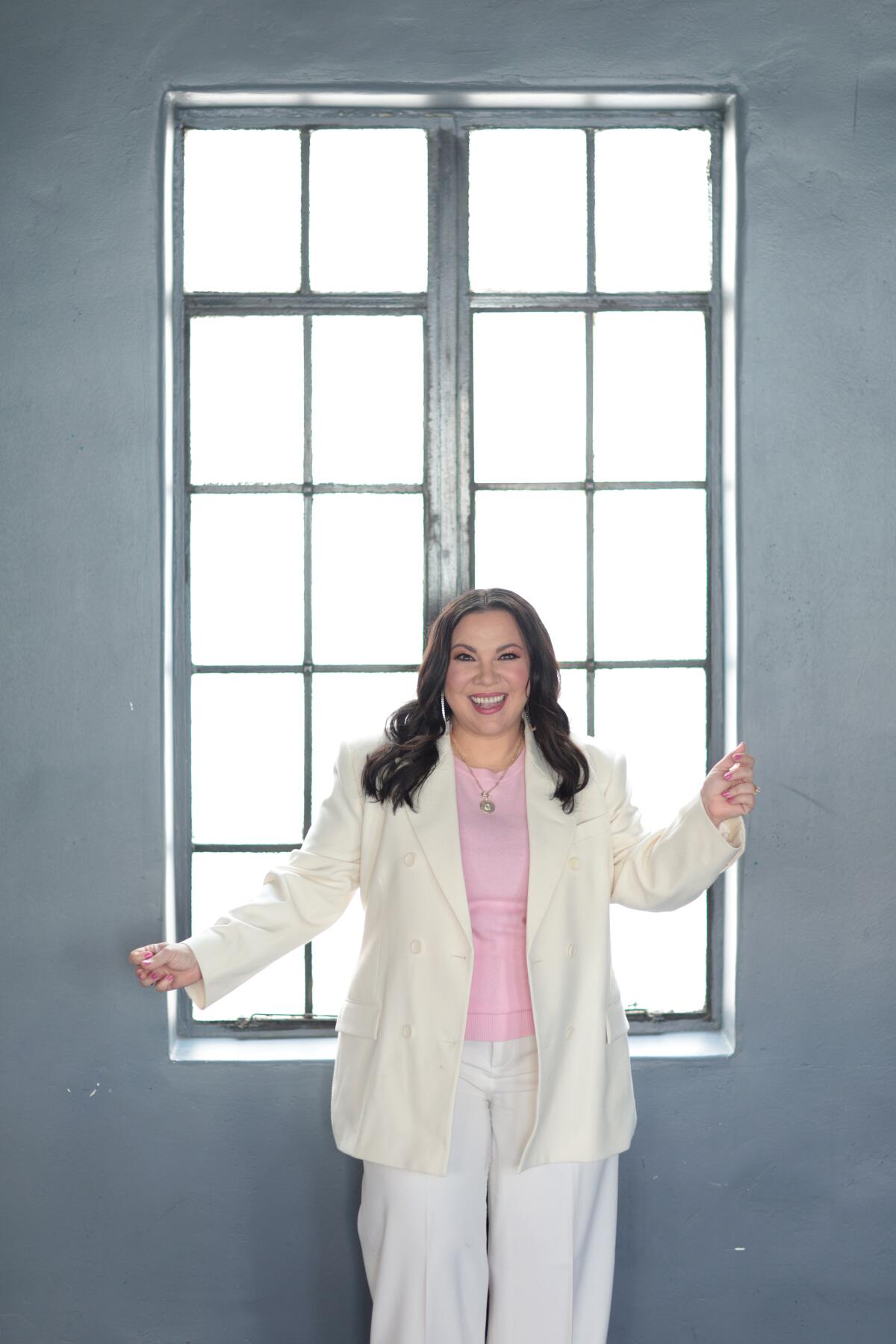

“I hope the audience laughs a lot and then talks for hours,” said Gloria Calderón Kellett.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

It is a bittersweet milestone that his play is the first Latino commission in the Pasadena Playhouse's 100-year history. So I love that you highlight the city. YoIndigenous roots in the script when matriarch Ilana says: “I was born in Mexico. “It’s just not called that anymore.”

The idea of America as the “great experiment” is very interesting, and who feels entitled to this land is fascinating, because it's not theirs either. And I just had to challenge the idea that anyone feels entitled to this place more than anyone else, with the exception of the natives who are actually from this land.

In fact, this is the first play I've written that is specifically Latin. All the plays I've written before were an answer to what I didn't find when I was auditioning as an actor; they were mainly for me and my friends, just existing as humans in the spaces. And those plays worked well for me because they gave me personnel for television shows.

Do you feel pressure to premiere your first Latin work in Los Angeles?

I know that a story cannot speak to all experiences; This is this specific family at this specific time on this specific land.

I'm really proud of the fact that this work exists. Our stories are only really involved when we're in trauma or when we're glorified drug dealers, and that's what people who don't know the people in my community think we are, because they don't know themselves. Latinos are 20% of the US population, and they are still only 5% [of actors in leading roles], and I can't even imagine what the theater figures are. I'm curious to know how many Latino productions are being made, and of those productions, how many are border stories or drug narratives, and how many are just Latinos living their lives and being happy.

And the other thing is that we are always poor, and that 100% exists, but I also know many Latinos who are prospering. That is why it is very important for me to show that in this land there are Latinos who live in big houses, who send their children to college and who have thriving businesses. And yet, they still walk around with many of these issues of identity and connection on their shoulders.

Carlos Gómez, Nico Greetham, Isabella Gomez and Lana Parrilla in “One of the Good Ones” at the Pasadena Playhouse.

(Jeff Lorch)

How have your years writing for television benefited your writing?

I learned a lot working with Norman Lear. Norman loved the theater and, as he wanted to bring the theater closer to the everyday family in his home, his multi-camera comedies were very different: the proscenium, long scenes, pages and pages without jokes. Because it wasn't always about the jokes, it was about the conversation. You are there to tell a story; Sometimes it's funny, sometimes it's not. People processing their feelings may mean acting out, staying silent, or feeling uncomfortable; It can be scary and then fun again. Real life is all of those things. That was the kind of comedy he liked and that's the kind of comedy I like.

For this play, I can sit with that carefully: no scenes, one location, all in real time. It's about generating tension with the live audience and not letting them free until the end.

What has been the most difficult part of writing this work?

The biggest challenge for me is the fact that there is so much I want to say. I feel like it could last four hours! I say to myself, “You don't need to understand everything in this one work. You don't have to fix everything. Just tell this story.”

“I hope this program is successful and leads to many more stories where the focus is on prosperity, not trauma,” said Gloria Calderón Kellett.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

What is your hope for “One of the Good Ones” after this run ends?

Whether it's a pilot or a play, I always love doing new work and this has been a wonderful opportunity to stretch my creative muscles. I would love to continue developing it in other theaters and am hopeful that it will lead to conversations, healing and mutual understanding among audiences.

I also think a lot about who can hold the microphone and tell a story. I'm trying to do it in a way that's inclusive and responsible for what I want the future to be like. So I hope this show is successful and leads to many more stories where the focus is on prosperity, not trauma. And I hope they come from many different points of view, because they call me “unicorn” a lot, as if I were the only one, right? No, I promise, I'm not. There are more of us and we have work to do.

'One of the good ones'

Where: Pasadena Theatre, 39 S. El Molino Ave., Pasadena

When: Wednesday to Friday 8 pm, Saturdays 2 and 8 pm, Sundays 2 pm. Ends April 7.

Tickets: Starts at $35

Contact: (626) 356-7529 or Pasadenaplayhouse.org

Execution time: 1 hour, 30 minutes