As the acclaimed “May December” heads into what is sure to be a multi-nominated awards season, director Todd Haynes and screenwriter Samy Burch find themselves on the receiving end of one of the questions their film raises: What Do filmmakers owe people? Who inspires the stories they tell, particularly when those stories involve abuse or exploitation?

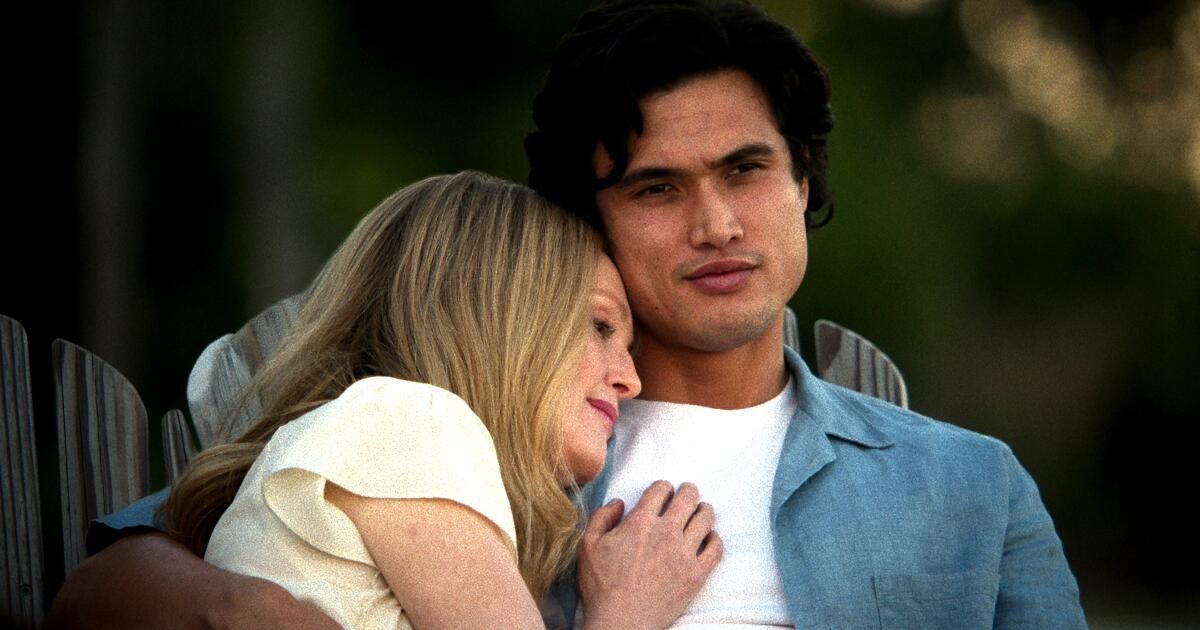

“May Dec” follows Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), an actress, as she visits the home of Gracie (Julianne Moore) and Joe (Charles Melton), an infamous couple who began an intimate “relationship” when Gracie was 30 and Joe was 13 years. Gracie was convicted of rape and spent several years in prison, but they eventually married; They have three children and live with as much privacy as their small town allows. Elizabeth has been cast as Gracie in a movie and wants to spend time with them as research.

Although certain details have been changed and the main plot is fictional, “May December” is obviously inspired by the headline-making scandal of Mary Kay Letourneau, who raped and eventually married her former sixth-grade student Vili Fualaau. In fact, some of the dialogue was taken directly from interviews given by the couple over the years.

This week, Fualaau, who divorced Letourneau in 2017 but was with her until her death in 2020, expressed his displeasure with the film and the fact, ironically, given the film’s narrative, that no one had consulted him while making it. .

“If they had contacted me, we could have worked together on a masterpiece. Instead, they chose to make a copy of my original story,” he told the Hollywood Reporter. “I feel offended by the entire project and by the lack of respect that has been given to me, who lived a real story and I am still living it.”

This is not a good look for “May December,” which Burch described in these pages as a “satire of the industry and the vampiric nature of playing real people who are alive,” but neither is the filmmakers’ decision not to involve Fualaau nor his unhappiness is unusual.

When working with historical or highly publicized material, writers and filmmakers often decide that the story they want to tell will not benefit from consulting or informing those who inspired it. Even when it comes to biographical films, which “May December” certainly is not.

“Maestro” may have garnered the full participation and well-publicized blessings of Leonard Bernstein’s children, but Sean Durkin, who made “The Iron Claw,” another awards contender this year, did not contact the surviving brother. by Von Erich. Kevin, until after he had written the script detailing the history of the famous wrestling family, which, for dramatic reasons, completely omitted one of the brothers. Kevin Von Erich (played by Zac Efron in the film) has said that he understands the omission, but rejected the representation of his father, Fritz (Holt McCallany).

Inevitably, any movie or television series made or inspired by real events will make someone, somewhere, deeply unhappy.

Vili Fualaau, center, in 1998.

(John Froschauer / Associated Press)

The late, great Olivia de Havilland sued, at age 100, Ryan Murphy for his profane and gossipy depiction of her in “Feud: Bette and Joan.” Soccer star Michael Oher, who earlier this year accused the Tuohy family of taking money earned from his participation in “The Blind Side,” took issue from the beginning with the film’s depiction of him as “silly”. Amanda Knox has repeatedly criticized film versions of her story (she was wrongly convicted of murder in Italy and imprisoned for four years before being exonerated), particularly the film “Stillwater,” starring Matt Damon, in which the protagonist inspired by Knox was actually guilty. .

More recently, nearly every living historical figure depicted in HBO’s “Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty” disparaged its accuracy, and friends and supporters of the British royal family recently pressured Netflix to add a disclaimer of “ This is a fictional dramatization of “The Crown.”

De Havilland lost his lawsuit (and his attempt to take it to the Supreme Court); Free speech laws offer broad protection to fiction and fictional stories, and with good reason: without the acceptance of a literary license, some of the best and most powerful films, TV shows, and novels would not exist.

But if writers and directors have no legal obligation to the public figures at the center of their stories, do they have a moral obligation? Not all inspirations from public figures are the same; There is a difference between the Queen of England and a man known for marrying the woman who raped him when he was a child.

In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of the effect that true crime stories, however fictional, can have on the people involved. For example, #MeToo spinoff films have emphasized the importance of respecting survivors’ experiences, and Ryan Murphy’s “Dahmer—Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” was criticized for retraumatizing the families of Dahmer’s victims.

No one would compare “May December” to “Dahmer” or even “Stillwater” (as Haynes and Burch have repeatedly said, the Letourneau/Fualaau relationship was a springboard, not a model), but there is no reading of that story, from the beginning . From the initial crime to the subsequent salacious publicity surrounding their eventual marriage, in which Fualaau is not a victim. No matter how sincere and fine a reimagining of his life may be, the decision not to involve him in some way is troubling to say the least.

Especially since the film directly addresses the exploitation of Hollywood adaptations. In “May December,” Elizabeth’s encounters with Joe seem to offer, at first, hope for liberation. She sees what the young man, still very much in thrall to Grace, does not: that the “relationship” began when Joe was too young to consent to it and continued when he was still too young to understand what it would cost him.

But Elizabeth also uses Joe: her “investigation” extends to having sex with him and then almost pushing him out the door. While the character of Elizabeth, rich in narcissism of the “creative process,” embodies Hollywood, “May December” portrays our thirst to retell sensational events as destructive. Glimpsed at the end, the film Elizabeth is working on seems far from high art, which adds insult to injury.

The power of “May December” comes from Grace and Elizabeth’s incessant battle for, if not the truth, then narrative control. In fact, the only “good” main character in the film is Joe, who is portrayed, tragically, as something of a hapless bystander in his own life.

Which, given the decision not to involve Fualaau, feels awkward, like the filmmakers are trying to have their cake and eat it too.

Yes, the people who inspire “based on true events” movies and series that we love are often unhappy with the cinematic results. But, as with the renewed discomfort over “The Blind Side,” Fualaau’s words seem more poignant and important than, say, Magic Johnson refusing to watch “Winning Time” or Judi Dench protesting the inaccuracies of “The Crown.” .

Unlike the Lakers, the royal family or Olivia de Havilland, Fualaau is not a public figure beyond the only thing the world knows about him; Like Knox and, to a lesser extent, Oher, he was thrust into the public eye when he was young, vulnerable and a victim of circumstance, which in Fualaau’s case meant the victim of a crime.

Mary Kay Letourneau in court in 1998.

(Alan Berner/AP)

As Knox recently pointed out in a lengthy social media thread reacting to Fualaau’s comments, there is no legal way for public figures to control how they are used in fiction. Again, for very good reasons. Writers and artists use familiar figures as cultural touchstones to tell all kinds of stories, many of which have little to do with the actual people or events that inspired them, and audiences are reasonably expected to understand this.

Some of these stories will be good, some bad, and some great; historians will make lists of corrections, critics will express outrage or appreciation, and we will all be able to discuss the complicated nature of fact, fiction, myth, memory, and narrative, which is always a good thing.

But sometimes it’s worth remembering that at the center of those touchstones are real people who, often without any intention of their own, watched helplessly as their stories fell into the public domain.

This is one of those moments.