“It's the gateway drug to the thrill of being an enfant terrible,” is how writer Jon Robin Baitz describes episode 3 of “Feud: Capote vs. the Swans,” called “Masquerade 1966,” a look at the famous who's who by Truman Capote. /who is not the black and white dance. “It's what happens when a writer as talented as he is becomes a kind of public figure, subsumed by being an arbiter of what matters and what doesn't.”

The first two episodes exposed Capote's betrayal of the secrets of his high-society clique and its immediate consequences. Baitz and executive producer Ryan Murphy needed a contrasting flashback to when the author, played by Tom Hollander, was full of attention and “dancing as fast as he could,” Baitz says. The self-mythologized evening in New York that he organized was also, Baitz says, “the Titanic three nights before the iceberg.”

According to Baitz, it was Murphy's “magnificent arrogance” to contextualize “Masquerade 1966” as never-before-seen footage shot by Albert and David Maysles, nonfiction filmmakers celebrated for the intimate style known as “direct cinema.” Thus, we see the black-and-white mockumentary that never existed, but could have shown a disturbingly bloated ego eager to be immortalized. “The Maysles are figures of great integrity,” Baitz says, “so it's interesting to pit them against Truman, who is unruly.”

The idea for the episode wasn't all that fantastical, since the Maysles actually filmed Capote at the time during his book tour, “In Cold Blood,” material Hollander mined for “the music of his voice,” the actor says. “It's Truman at his peak, at his most alive, most confident and most cocky. You can see how much he thinks of himself. He can only end badly.”

What director Gus Van Sant and cinematographer Jason McCormick had to do was recreate the look of a handheld 16-millimeter camera shooting black-and-white Kodak film with an active zoom lens, the square frame far away from the widescreen, multicolor. Glamor seen in the rest of the series. Additionally, with the production's block shooting style, scenes from “Masquerade 1966” were often on days with scenes from other episodes. But for McCormick, moving on to the almost improvised mockumentary of “Masquerade 1966” after such careful and studied filming was “like playtime.”

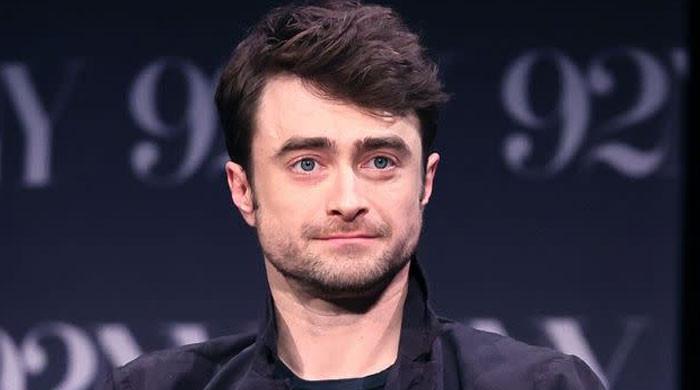

Demi Moore plays Ann Woodward in “Feud.”

(currency exchanges)

“You go from a world of color and control and a much more composed camera, lit a certain way, to just hitting a light on the wall, not caring if there's noise or grain, and it was totally liberating,” McCormick says. to fulfill Van Sant's vision for the episode. “I could have shot like that forever.”

There was also the thrill for McCormick of operating the RED monochrome camera himself, playing the role of someone pointing a lens at Truman Capote as he prepares, runs and acts as a confidant to his nervous swans, each of them: Babe Paley, by Naomi Watts, Slim Keith by Diane Lane, Lee Radziwill by Calista Flockhart and CZ Guest by Chloë Sevigny, suspicious that someone is recording everything. It is a constant interaction between interpretation and subtext.

“I went into that head space of 'I'm one of the Maysles brothers,'” says McCormick, who would have to think like a documentarian on the fly while still capturing what the story needed. “There was a playful energy with the actors and it was fun for them. They broke the fourth wall. See Naomi carry the camera trying to [stop the filming], you have to sell it. It's a lot about spontaneity. I have to pretend I don't have it figured out. I can’t be perfectly in rhythm.” McCormick found himself operating in microseconds of reactivity to a false discovery. “It's a subtle thing between reacting and anticipating.”

One such moment, one of Baitz's favorites, occurs during the dance when Capote is drunk, dancing alone, talking to himself, and the camera “catches” Radziwill's critical expression of Flockhart looking at him. “This is the genius of Gus,” says Baitz, “that the Maysles are capturing what's beneath the surface of a scene. It's about how to make the camera do the work that Truman doesn't. “It's espionage.”

However, what we learn in the final moments, as we move from Maysles' images to Capote's subjective vision, is that his late mother (Jessica Lange) is with him, enjoying an elite life that he could never achieve. . “That was very clever,” Hollander says. “That the ball was for her. Lee says, 'Look at that poor drunk,' and then the whole episode takes on color and you discover that he's not alone, he's dancing with his mother. It is so beautiful.”

Hollander and Lange rehearsed diligently for the wide crane shot that closes the episode, but the shot they thought was perfect was not the one used. “It was one where Jessica and I stepped on each other's toes, lost our rhythm, and made faces,” Hollander recalls. “But the actors can never see what they are a part of because they are doing it. The director has a divine perspective and Jason and Gus were moved. There were a few moments during filming where Gus was close to crying, and that was one of them. Jessica and I would have said, 'Oh, honey, that was horrible!' But it was not like that”.

It's also an ending that, once again, in Baitz's opinion, suggests an underlying truth, even beyond the scope of a documentary. “Truman is animated by the need for his mother's approval,” Baitz says. “Suddenly, color, even if it's pure fantasy, is real.”